The Camera Man

Gillian Darley

Last year I wrote a brief introduction to The Leaves of Southwell by Nikolaus Pevsner, a facsimile edition of King Penguin No. 17, in a series that Pevsner himself was editing. Gothic architecture is not my speciality, but I have a lingering interest in the author. Pevsner, whose name is inescapably attached to the Buildings of England, seems to have begun work on this little volume very soon after he was released from internment and had begun to pick up the pieces of academic life in Britain. Although published in 1945, it was probably written in 1942.

The text is a celebration of the naturalistic carvings of Southwell Minster, the work of itinerant craftsmen, whose subtle stylistic differences Pevsner happily puzzles over: ‘The individual craftsman,’ he writes, ‘must have had a considerable amount of personal liberty.’ He continues:

Could these leaves of the English countryside, with all their freshness, move us so deeply if they were not carved in that spirit which filled the saints and poets and thinkers of the 13th century, the spirit of religious respect for the liveliness of created nature?

Pevsner prefaced his text with St Francis’s ‘Canticle of the Sun’ and some verses from the Carmina Burana. ‘In an inconspicuous part of central England,’ I wrote in my introduction, ‘he had found and could celebrate a distillation of art and life from across continental Europe.’ Born a Jew, Pevsner was not protected by his conversion to Lutherism. He lost his university post in Göttingen in 1933 and left Germany for England two years later. His mother, who stayed in Germany, took her own life early in 1942 to avoid deportation.

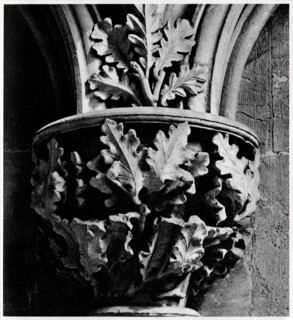

But the richness of the book lies above all in the photographs, printed in the best photogravure available in the postwar months. They were the work of an Anglo-Saxon historian, the principal of University College Leicester, a man with a particular passion for the camera. They are evidence of an intensely collaborative project. In the clear light and unimpeded space of the minster’s chapter house, Frederick Attenborough mastered the capturing of natural light on stone and the framing of carved vegetation that, in places, breaks away from the capitals and creeps up the mouldings. I confess I had given the technology of the process little thought, seduced rather by the results.

The book was published in July by Five Leaves Publications of Nottingham. Copies were sent to the copyright holder. Soon afterwards, I received a letter. ‘I can claim to have played a small part in the book’s creation,’ David Attenborough wrote:

When I was a boy I regularly accompanied my father on his photographic forays carrying his huge plate cameras, and I guess I must have been about fifteen when he started on the Southwell project. He did not use any artificial lights, so one of my jobs, apart from porterage, was to sit looking at the sky, trying to predict when there might be a shaft of sunlight and exactly where it would fall. So I remember some of the Southwell capitals very well indeed!

Over the years, the photographer’s assistant told me, he had picked up second-hand copies but a new edition makes him ‘hugely grateful’.

Comments