The Heat Wave in Northern India

Skye Arundhati Thomas

In May 2022 temperatures in Northern India hit 49°C. The Indian Meteorological Department declared it a ‘heat wave’ and in a heat wave, public infrastructure begins to fail: pavements buckle, railway tracks warp, and electrical grids are strained by increased use of air conditioning. Fires start in dry fields. Industrial plants require more water for their cooling systems, straining already reduced supplies. Crops are ravaged. A heat wave is also a national health emergency. At a wet-bulb temperature of 35°C – that is, the equivalent of 35°C and 100 per cent humidity – the human body can no longer cool itself by sweating. You overheat and die within hours. Throughout May, regions across India saw consistent wet-bulb temperatures between 25 and 33°C.

By 31 May, national news agencies were reporting that there had been 2200 deaths across the country. A survey in Andhra Pradesh showed that 1636 people had died in that state alone, casting doubt on the accuracy of the national numbers. There were no announcements of precautionary measures, emergency medical services, or clear solutions for the faulty and overwhelmed power grids. Instead, cities and villages faced hours-long power cuts as the humidity index soared. Some states closed schools early, and unions declared the stoppage of certain services (the taxi union in Kolkata, for instance, was quick to do this).

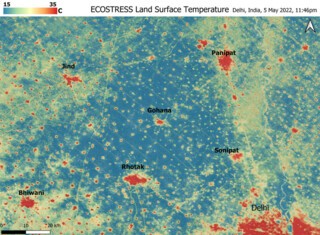

Nasa’s Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer (Ecostress) released satellite images of the weather spikes in and around New Delhi, which showed fiery red pockets dispersed evenly over the city. The heat wave didn’t come out of nowhere: temperatures have been steadily rising over the last five years.

In the 2022 Yale Environmental Performance Index, India comes bottom of a list of 180 countries. Worsening air quality and increasing greenhouse gas emissions are urgent concerns. Four nation states, according to the report, will account for 50 per cent of global emissions by 2050: China, India, the US and Russia. Only Indonesia discharges as much plastic waste into the sea as India.

The head of the Sri Lankan electricity authority told a parliamentary hearing on 10 June that the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, had put pressure on the Sri Lankan president to hand a 500-megawatt wind power project to the Adani Group. (He later withdrew the claim.) The Adani Group is valued at over $100 billion. Its holdings involve defence systems, national infrastructure projects, sports teams, data centres, food processing companies, real estate, agriculture and energy. In 2015, the year after Modi was elected prime minister, the Group began buying up coal mines across India and Australia, as well as cargo ports and container ships. In 2019, the Modi government changed the law so that Adani coal plants could be designated Special Economic Zones.

Gautam Adani founded his import-export business in Gujarat in 1988, gradually taking over and refurbishing the port of Mundra. Beside it, he constructed the country’s largest coal-fired power plant. In 2003, when several Indian industrialists tried to hold Modi, then chief minister of Gujarat, accountable for the mass violence that had been provoked by him and his party, Adani instead offered his unconditional support. Days before Modi was sworn in as prime minister, it was an Adani private jet that flew him to New Delhi from Gujarat. Adani has often stressed that ‘nation building’ is an important part of his business’s purpose, and in the first six years of the Modi regime, his net worth surged by nearly 230 per cent. He is now richer than Bill Gates. The FT has described him as ‘Modi’s Rockefeller’.

He boasted this week that ‘we are leading the race to turn India from a country over-reliant on import of oil and gas to a country that might one day become a net exporter of clean energy.’ In recent years however the Modi regime has repossessed land that was once designated as protected and, with the help of the Adani Group, reinvigorated a national coal economy. In 2018 police officers invaded the lands of the Santal community of Jharkhand. In the small farming town of Godda, eyewitnesses claimed there were ten police officers for every villager, and they strong-armed community members who tried to resist them. The police were escorting a demolition squad from the Adani Group, who proceeded to tear out paddy fields, uproot palms and cut down a mango orchard. They were clearing the way for the construction of a new power plant: coal from the new Carmichael mine in Australia – another Adani project – would be burned there.

The Godda plant was also declared an SEZ, producing energy primarily for export. Locals who protested against it were charged with criminal trespassing and incarcerated. People who live near the plant have suffered the cost: ash in the air, a drastic increase in temperature, polluted water and sky. There are 150 reactivated coal mines in Jharkhand alone: it is one of India’s poorest states but also its most significant producer of energy. Total demand this summer shot up to more than 210,000 megawatts a day. About 70 per cent of that is produced by burning coal. There are no signs of its being phased out. As the heat wave raged, petrol and diesel prices soared. In Jharkhand, locals endured power cuts of over ten hours a day.

This piece is part of the LRB’s collaboration with the World Weather Network.

Comments