The Woodcutter’s Axe

Arianne Shahvisi

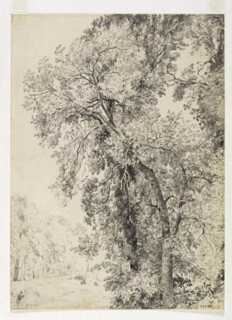

An airborne disease originating in East Asia is sweeping through more densely populated areas of the British Isles, spreading from one individual to the next, and killing more than 90 per cent of those it infects. Millions will eventually be dead, costing the economy £15 billion. This is the last stand for the European ash (Fraxinus excelsior), one of Britain’s most common native trees, whose pointillist crown will soon vanish from the skylines of streets, woods and hedgerows, its susurration dropping out of the woodland symphony.

Until I learned of their prognosis, I was one of the four in five people who could not identify an ash tree. Now I see them everywhere. I have opened my curtains to a sprawling ash every morning for years; all day long I overlook a straggly individual from my desk. Both are healthy, but I’ve added them to the list of things to worry about.

Ash dieback, caused by the fungus Chalara fraxinea, starts in the tips of leaves and creeps in from the extremities like frostbite: the trees literally die back, inwards, inch by inch. Leaves wilt and blacken, and are shed like sneezes, littering the ground, to be picked up on feet and tyres and stomped into the earth of other places. In summer, the fungus in the leaf litter spits out spores that surf the wind and can settle on the leaves of trees ten miles distant; and so the fatal disease ripples across landscapes, a few miles at a time. With their crowns thinned, the trees’ ability to absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen dwindles. As the disease snakes along the branches, diamond-shaped cankers erupt on the bark, spreading vertically and in many cases encircling the trunk, choking its supply of water and nutrients. The tree starves and dies, or in its weakened state succumbs to other infections, that cause it to rot and collapse.

Like other infectious diseases, ash dieback is a consequence of globalisation: infected saplings were imported to the UK from continental Europe, smuggling in the fungus which was winding its way west more slowly from the forests of Japan and Korea, where the trees are resistant. In the years to come, more than a hundred million ash trees across the British Isles will die. If they aren’t replaced, three billion kilos of carbon dioxide a year won’t be captured, equivalent to the annual emissions of 650,000 cars. Our wildlife will suffer, our towns will be uglier, our air will be less clean.

It isn’t globalisation’s biggest arboreal crime. We are now losing a patch of forest in the Global South as large as a football pitch every six seconds. Every year, an area of old-growth forest the size of the UK is felled or burned to meet British demand for beef, palm oil, timber, leather, rubber and cocoa.

Even the thinnest ash stave can bear enormous force without splintering, which makes it the wood of choice for snooker cues, hockey sticks and oars. It is also traditionally used for the handles of axes. In his 1916 collection Stray Birds, Tagore wrote:

The woodcutter’s axe begged for its handle from the tree.

The tree gave it.

It’s a metaphor for Britain’s looting of India, but can be taken more literally: timber extraction under colonialism was one of the greatest deforesting forces in history. Having all but exhausted its own woods, Britain ravaged its colonies, transforming vast swathes of ancient forest into monoculture plantations, leading to biodiversity loss, flooding, desertification and displacement, and setting the scene for the neocolonial economies that are gobbling the rest.

Tagore’s verse belongs to a broader set of fables that centre on the disloyalty of a wooden axe handle to the forest it fells. They warn us about acting against our own interests. With that in mind, it is worth noting that deforestation is a major driver of novel infectious disease, as species whose habitats are destroyed are forced into more frequent contact with humans and other animals, increasing the likelihood of infections crossing the species barrier.

And then there’s the warming. In June this year, thermometers read 38°C in the Arctic circle; in August, the highest air temperature was recorded in Death Valley, at 54.4°C. Ash trees in the UK are now leafing ten days earlier than they did a few decades ago. Elsewhere, heat-stressed trees are suffering deadly xylem embolisms that emit disquieting ultrasonic screams.

On the hottest nights, the stridulation of crickets sings out another warning. You can estimate the temperature in centigrade by counting the number of chirps in 25 seconds, dividing by three and adding four. A tree ecologist in Richard Powers’s novel The Overstory notes the dizzying rise: ‘For sixty years, the nighttime orchestra all around her has been playing one of those folk dances that keep speeding up until all the players tumble in a heap.’

Photosynthesis is our best defence. Instead, governments are ploughing money into the struggle to contrive machines that hoover up CO2 from the sky, in an endeavour reminiscent of the scholars Gulliver encounters in Lagado, trying to extract sunbeams from cucumbers.

Comments

Deforestation continues to be a global blight - wood pellets anyone?

Fact check(s): the Arctic Circle regularly (OK, irregularly) has had temperatures close to 40C & the hottest temps in Death Valley date back to 1913 (though, apparently, they are now disputed).

Long live la frêne!

The luck kicked in when lockdown happened in the best summer ever and I cycled all over London watching nature take over.

Very nice piece - I'd have a line of Tagore over thousands of pages of Rushdie any day. He understood the nature of people.