At the Théâtre de la Ville

Sam Kinchin-Smith

Every generation gets the scam artists it deserves. To a list that includes Elizabeth Holmes, Dan Mallory and Billy McFarland – whose spectacularly doomed attempt to stage Fyre, a music festival in the Bahamas, is once again a byword for debacle, thanks to the simultaneous release of documentaries on Hulu and Netflix – should we now add the name Ilya Khrzhanovsky, the Russian film director responsible for Dau, which finally opened in Paris at the end of January, and closes this weekend?

James Meek wrote about its origins for the LRB in 2015: a three-year shoot that saw a huge cast and crew going native in a crazily detailed, aggressively policed reconstruction of a Soviet scientific institute on the edge of Kharkiv, in order to tell the story of the life and work of the theoretical physicist and free love enthusiast Lev Landau. A decade of post-production in a Piccadilly townhouse followed. Thirteen films are now showing at the Théâtre du Châtelet, the Théâtre de la Ville and the Centre Pompidou.

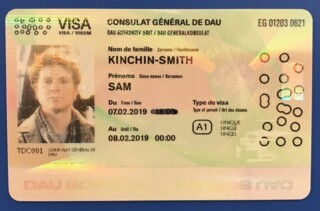

Visitors have to apply for a ‘visa’ online, by providing basic details, a passport photo and, if you’re willing to pay for the full experience, answers to psychometric questions that will, the website claims, enable their ‘algorithmic system to tailor your Dau visit specifically for you’. If you’re lucky, your application will have been processed by the time you get to the visitor centre, and your visa will be waiting for you: a printed card that will be checked and scanned several times before you get to see anything, and eventually synced with a Dau device, which will try to tell you where to go, what to see. Your phone will be taken from you and checked into a locker on entry – a smart move by the production team, considering what phone footage did to Fyre.

I didn’t provide any psychometric data and didn’t realise I was supposed to pick up a Dau device until quite near the end of my visit. This meant I was able to move freely between film screenings instead of watching only the one (or the concert, or the lecture) my device told me to. ‘But the movie has already started,’ I was told on my way into one screening, as though that mattered.

This elaborate multimedia presentation has been designed as a continuation of Dau’s ‘vast collaborative experiment’, turning visitors into participants and subjects. Celebrity scientists and mathematicians including Carlo Rovelli, Dimitri Kaledin, David Gross and Shing Tung Yau accepted the offer of working residencies at the institute, where they engaged in anachronistic research. Marina Abramovic played a visiting professor of anatomy. Was all this experimentation pointlessly performative, or is the Paris premiere an avant-garde data mining exercise of the kind we’ve been encouraged to worry about since the Cambridge Analytica scandal, hiding in plain sight?

‘Your data will be kept confidential and will not be shared with any unauthorized third parties, in compliance with the GDPR,’ the website says, but it may be worth bearing in mind that most of Dau’s apparently bottomless budget has been put up by Sergei Adoniev, a Russian telecommunications oligarch, who recently had his Bulgarian citizenship rescinded because of a twenty-year-old fraud conviction in the United States.

To sidestep the risk of being blackmailed, I perhaps ought to confess that I spent most of my allotted time in one of the rushes booths – where you can flick through endless reels of unedited, but meticulously contextualised, footage of meetings, experiments, mealtimes and so on – watching the residents of the institute having unsimulated sex, which was rivetingly uncontrived and therefore far more truthful than everything else I saw at Dau, although it’s hard to see how troubling questions of coercion and consent won’t eventually catch up with Khrzhanovsky, a former ‘pickup artist’.

Landau, played by the Greek-Russian conductor Teodor Currentzis, who seems to have had a whale of a time, didn’t appear in either of the films I saw. The first depicted some of the institute’s cleaners talking, laughing and drinking, before one elderly woman vomited into a bucket. Their Russian dialogue was translated by an earpiece in which a male monotone delivers everybody’s lines, UN-style: an authentic representation of mid-century dubbing, apparently. I was quite hypnotised by the long uninterrupted shots (how did the editing take so long, when there’s no editing?) until my girlfriend, who has spent quite a bit of time on film sets, whispered: ‘It’s like the extras have taken over.’

I thought I was interested in Dau because I would have liked to have spent a few months on set. (Everyone who bought a ticket for Fyre felt similarly about the festival’s promotional shoot: ‘What the commercial was, was what everybody wanted,’ the documentary concluded.) ‘If the films were good,’ Meek wrote in the LRB,

they would be good, but if they were poor, they could always be represented as the mere shadow of an extraordinary work of immersive theatre that had been experienced by a handful of lucky people in Kharkiv … we were invited to contemplate a marvellous, yet to be completed work, but ended up feeling subject to a meticulous description of a wonderful party we hadn’t been invited to.

It’s hard to imagine a more bracing cure for this condition than the sudden realisation that time at the institute would have been mostly spent sitting around with a bunch of failed actors enthusiastically remaining in character, waiting for the camera to pass by.

The second film I saw was structured around a Marxist-Leninist lecturer describing, with evident thrill at the weight of the dramatic irony, how the trajectories of history may result in a hyper-nationalism taking hold in the motherland in 2020, or thereabouts. These scenes were interspersed with footage of skinheads led by the real-life neo-Nazi Maksim ‘Tesak’ Martsinkevich, invited by Khrzhanovsky to destroy the set at the end of the shoot, engaging in a campaign of ‘focused terror’ against visiting ‘faggot’ scientists: vanilla scare tactics compared to the crimes Martsinkevich has since been imprisoned for (he’s currently serving a ten-year sentence in a corrective labour colony for attacking drug dealers). Tesak (‘machete’) is an undeniably compelling presence, and Khrzhanovsky’s decision to bring him to the institute is undeniably provocative, as well as self-indulgent and dangerous.

Some sequences – in particular, those starring the institute more than its residents – look amazing: an uncannily detailed vision of the past, through a glass, darkly. The most mysterious thing about this most shadowy of projects is how the production team responsible for the logistical disasters in Paris, not to mention last year’s cancelled premiere in Berlin, managed to create an event, and a narrative around it, whose mystique has endured for more than a decade – and which will no doubt outlive this silly unveiling, too.

Comments