Peterloo and After

Harry Stopes

Eighteen people were killed when soldiers charged the meeting at Saint Peter’s Fields, Manchester, on 16 August 1819. Elizabeth Gaunt tried to hide in a hackney coach. She was grabbed by special constables who beat her with their truncheons. Covered with blood, she was dragged to a house nearby and flung before the magistrates. She spent a day and a half in jail without food, before being remanded on a charge of high treason. She was eventually released without charge after eleven days, during which time she had miscarried.

A month and a day after the Peterloo massacre, as many as 20,000 people assembled on Briggate Moor, Leeds bearing a black banner: ‘We mourn for the Murder of our Manchester friends.’ There was little shame on the part of those responsible. In Oldham, almost all of the innkeepers had been sworn in as special constables. The Manchester Observer’s correspondent described these ‘truncheon heroes’ meeting returning survivors of Peterloo ‘with a smile of satisfaction and exultation pictured upon their fat bloated countenances’. ‘At Waterloo there was man to man, but at Manchester it was downright murder,’ a friend of an Oldham man, John Lees, told the inquest into his death.

On the first centenary of Peterloo, there was a march from Albert Square to Platt Fields. They carried a red bonnet on a pole, and sang the ‘Marseillaise’ and ‘We’ll wave the scarlet banner high’. At Platt Fields, speakers from the Independent Labour Party addressed a crowd that was, the Manchester Guardian sniffily observed, ‘smaller than one had expected’. The next day, the ILP’s James Hudson told a meeting at the Free Trade Hall that the workers had learned at Peterloo that their enemy was not imprisoned on St Helena: he was living in Manchester, and was their master, their landlord or their magistrate. For the Guardian, the lesson of Peterloo was that the sacrifice had been ‘not wholly vain, for thirteen years later the Reform Act was on the Statute book.’

To the extent that Peterloo has been absorbed into an official, smooth or safe narrative of British history, it is in this form: as the last bloody event in the march of progress whose subsequent steps were marked by legislation and the gradual expansion of political citizenship in the liberal mould. The authorities responsible for the massacre did not see it in this light at the time. It had been preceded by two decades of increasingly restrictive legislation against meeting and speaking in public. After Peterloo these rights were further restricted by the ‘Six Acts’, which criminalised marching with ‘flags, banners and other emblems’.

For their part, the victims of the massacre hadn’t assembled to demand the liberal polity that the Guardian would a century later credit them with having won. The radical politics of 1819 were ‘a hybrid phenomenon that posed problems of classification in a non-democratic age’, according to the historian Robert Poole:

Neither pre-democratic mob nor post-democratic demonstration, the reformers played out the role of unenfranchised citizens, presenting the government with the unanswerable physical presence of vast bodies of freeborn Englishmen and women assembled to proclaim their lost rights.

These rights were claimed not by the individual but by the community as a whole.

Peterloo represented a level of brutality, and mortality, not seen on mainland Britain since, though it’s hard not to hear contemporary echoes, however faint. Robert Brooks, a quartermaster in the Dragoon Guards, claimed that he ‘saw no violence used by the soldiers of any description’, and testified that ‘many of the mob in the confusion, fell down and were trampled upon by others, and many of their faces were cut, caused in consequence of such falling.’ Roger Entwistle, a gentleman, swore that he saw bricks, stones and sticks thrown at the Yeomanry, but ‘the Yeomanry so attacked and assailed had not used their swords either in striking or cutting or in any other hostile way whatever against any person whatsoever.’ He also claimed to have heard shots ‘fired by the mob’.

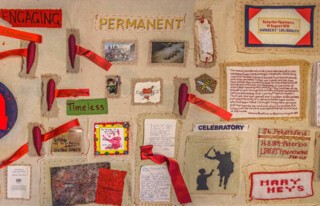

The Peterloo Tapestry was on display in Manchester cathedral last month. Made in 2016, it’s a ten-metre length of canvas onto which members of the public were invited to stitch words and images. The dozens of pieces include an extract from the diary of Henry Hunt, photos from Stonewall, a dove, a bee, ‘#JFT15’. One image, a silhouette of two figures, appears twice. A hussar – you can see the plume on his helmet – is leaning from his horse, about to swing his sword at the other figure, who has her arm raised. You can’t tell from the silhouette that she’s a woman, but you know that she is, because the image is adapted from John Harris’s famous photograph of a mounted policeman taking a swipe at the activist Lesley Boulton at Orgreave in 1984.

Comments

An estimated 5000 people marched to the slag heap Cinder Hills and were attacked by the Shropshire Yeomanry. Two men were killed and hundreds of men, women and children were injured.

Nine men were arrested and convicted. One of them, Tom Payne, was hanged 'pour encourager les autres'.

The event became known as Cinderloo. A campaign is underway in Telford to make these events better known, culminating in February 2021, the 200th anniversary of the event.