In Golgonooza

Inigo Thomas

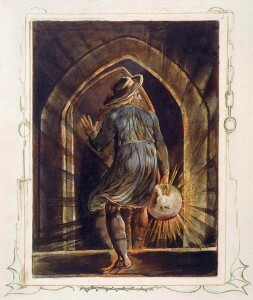

Two years ago, I counted 64 cranes from the top of Primrose Hill; now I count 96. Words attributed to William Blake are carved in stone on the hill's summit: 'I have conversed with the Spiritual Sun, I saw him on Primrose Hill.’ They were recorded by the poet’s friend, Henry Crabb Robinson. Blake told Crabb Robinson that God had spoken to him: ‘He said, "Do you take me for the Greek Apollo?" "No," I said, "that" – and Blake pointed to the sky – "that is the Greek Apollo. He is Satan.”’ Blake was against the Classical in all its forms, and in Regency London Classicism was the ruling aesthetic. The late 18th and early 19th-century expansion of London – the new church spires, the rows of terraced housing – was endless. Destruction and rebuilding are major themes in Blake’s longest poem, Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion. In Blake’s vision, Golgonooza – a city of the imagination, a version of London, only it’s the size of Britain, an endless ‘work in progress’ – was ‘ever building, ever falling’.

The Blake Society’s annual day-long pilgrimage through London took place on Saturday. The walk was led by Henry Eliot, the editor of Curiocity, who marched a group of around 15 of us to buildings and places associated with Blake. People came and went as the day progressed. Except for the three years when he lived on the south coast, Blake was always a Londoner. The walk began at 9.30 at a house on South Molton Street where Blake lived from 1803 to 1821. The ground floor is now a waxing salon. Blake’s birthplace in Soho has long gone; the building standing on the site is a concrete tower housing a TV company’s offices, whose receptionist sits beneath a neon sign that says ‘Heaven and Hell’. St James’s Piccadilly is the church where Blake was baptised. At night, the church is a shelter for the homeless; twelve people slept on the church’s pews that morning.

Down an alley off the Strand, where the house Blake died in stood, Steve, a poet in long black shorts, sandals and a blue velvet jacket, whose silvery hair and beard were definitely druidical, told me he had sold 20 handwritten poems for £20 each at a pub the previous night. And that he’d got drunk. He pointed out that in the alley where we stood, Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg met to talk about Blake in the mid-1960s. Steve said that there was once a menagerie on the banks of the Thames which had a tiger, and he implied that Blake might have heard its roar when he lived in Lambeth. If Blake’s work is hard to be exact about, Steve’s grasp of Blake's imagination seemed unlimited. It was the anniversary of Blake’s meeting with Constable, Steve said, when Blake looked at some of Constable's work and exclaimed: 'Why, this is not drawing, but inspiration!' Constable replied: 'I never knew it before; I meant it for a drawing.' But who knows if that's true.

We went into the convent in Hyde Park Place built at the turn of the 20th century to honour the Catholic martyrs hanged at Tyburn (Blake called it 'Albion's fatal tree'), Thomas More among them. In the crypt, relics of the martyrs stud the walls. Every second of every day, the nuns (the Benedictine Adorers of the Sacred Heart of Jesus of Montmartre) pray for them. It is, to say the least, otherworldly.

At Marble Arch I broke away from the Blake Society and walked south on Park Lane with the Solidarity with Refugees demonstrators to Parliament Square. The police lining the march gave the impression they hadn’t counted on the demonstration becoming so large. They halted the crowd, moved it on, stopped it again, as if they weren’t sure what to do with it. But then the demonstration’s organisers hadn't anticipated anything as big as this either. Billy Bragg led the crowd in singing 'The Red Flag', which isn’t the poetry of William Blake, but isn't unlike it, either.

The Blake Society’s walk ended at sunset at Bunhill Fields in the City of London, the cemetery where Blake is buried. Daniel Defoe and John Bunyan are also buried there, along with countless less well-known radicals and non-conformists. The future of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party is unclear, and much of the British press has, unsurprisingly, already written him off. But in Bunhill Fields on Saturday, the radicalism of Blake, Bunyan and Defoe appeared to have risen unexpectedly from the dead.

Comments

Hang it all man, have you given your fact checker the axe?