Six Characters in Search of a Lawsuit

Elisabeth Ladenson

A French tribunal decreed in February that all copies of Marcela Iacub’s latest book, Belle et Bête, carry a notice ‘informant le lecteur de ce que le livre porte atteinte à la vie privée de Dominique STRAUSS-KAHN’. Belle et Bête is written entirely in the second person, addressed to an unnamed man whose presidential aspirations had been brought to an end by a series of scandalous revelations starting with the accusations of a New York chambermaid. It begins ‘Tu étais vieux, tu étais gros, tu étais petit et tu étais moche,’ and continues in the same vein, recounting the narrator’s affair with the man, ‘le roi des cochons’, who likes to lick off her eye make-up and pour oil into her right ear so he can tongue it out. In another scene he asks her to suck his thumb while he talks on the phone with his wife. She ends their liaison, which does not involve more canonical forms of sexual intercourse, after he bites off her left ear and swallows it.

Iacub’s skirmish with DSK is only the most lurid of a large number of literary lawsuits in recent years. Camille Laurens, Patrick Poivre D’Arvor and Christine Angot have all been all accused of intruding into the private lives of people objecting to recognisable and unflattering portraits of themselves in ostensibly fictional works. The plaintiffs are most often ex-spouses or partners’ ex-spouses, though in 1999 Mathieu Lindon was convicted of libel for his novel Le procès de Jean-Marie le Pen.

There is a long tradition of this sort of thing in France; Roger de Bussy-Rabutin, Mme de Sévigné’s libertine cousin, was sent to the Bastille and then into exile by Louis XIV for the portraits of court figures in his Histoire amoureuse des Gaules.

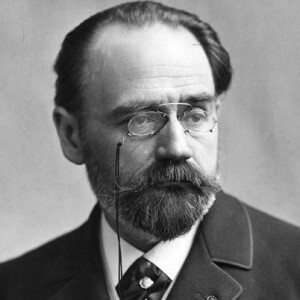

The first French novelist to be sued by one of his characters would seem to have been Zola. One of the characters in Pot-Bouille is M. Duverdy, a lawyer who’s besotted with his mistress, a sluttish actress he imagines to be a virtuous woman. When Pot-Bouille was serialised in Le Gaulois in 1882, Charles Duverdy, a lawyer and editor of La Gazette des Tribunaux, was disturbed to find he had a dimwitted, adulterous fictional double. What’s more, the non-fictional Duverdy lived very near the apartment building on the rue de Choiseul depicted in the novel. He went to the offices of Le Gaulois and asked that the character’s name be changed.

Zola refused, compared himself to Flaubert facing the imperial prosecutor in the obscenity trial of Madame Bovary 25 years earlier, and predicted the demise of the modern novel if writers were no longer free to choose their characters’ names. All his names, he said, came from the Bottin (which would later become the phone book), as was necessary for the modern scientific novel of observation. Duverdy sued the author and newspaper, which promptly published not only Zola’s open letters of protest but the proceedings of the court case too. The plaintiff’s lawyer pointed out that his client was the only Duverdy in the Bottin, and asked those present to consider whether they would want their names, and in particular those of their wives, sisters and daughters, to be dragged through the sort of mud depicted in Pot-Bouille.

Duverdy won the case, the character’s name was changed to M. Trois-Etoiles, and five more people whose names were in the novel – three Josserands, a Marie Pichon and a Vabre – came forward to demand that their names too be removed from the book. A reader named Mouret, however, wrote to Zola to assure him he had no objection to his name being used for Octave Mouret, the ruthless, skirt-chasing central character. After a brief interval during which Vabre was called M. Sans-Nom, Zola refused to change any more names, but Duverdy remained Trois-Etoiles throughout the remainder of the serial publication. The character was called Duveyrier when the volume appeared, as in all subsequent editions.