Remembering Sylvia Kristel

Rosemary Hill

Like many of my contemporaries I saw Emmanuelle in its much-censored British version at the Prince Charles Cinema off Leicester Square. I went with my first long-term boyfriend. We were both working in Foyles in our gap year, commuting in from Sevenoaks or thereabouts and I suspect that beneath the somewhat laconic discussion afterwards we were a bit shocked by it. I know for a fact that I was.

It must have been almost exactly ten years later that I met Sylvia Kristel when she opened her front door to me in Ghent. It was just after Christmas. Ghent, which I had never seen before, was looking like a scene from Breughel, the snow thick on the hump-back bridges over the canals, the cafes brightly lit and inside them tables covered with richly coloured Turkey carpets. I had just got married and was there with my husband, Christopher Logue. Christopher was an old friend of the Belgian writer Hugo Claus, with whom Sylvia had lived, on and off, since the 1970s. She looked at first sight a bit of a mess, hair on end, puffy eyes, and still in the afternoon wearing a lumpy towelling robe and big pink fluffy slippers, cigarette in hand. I was hugely relieved.

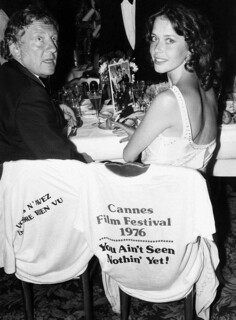

Since I’d first known Christopher he’d talked about his friend Sylvia. He was keen for us to meet as he felt she could help me. When Sylvia went shopping for clothes, he explained, she would take over the whole store and get all the staff fetching things for her, instead of cowering by the rails as I did, and when they’d been to France together she’d brought her own hair and make-up assistant and so had none of my ‘holiday hair’ problems. It was a while before I realised who ‘Sylvia’ was and that the trip to France had been to the Cannes Film Festival at the height of her fame. When I did work it out and put it to him that as a film star and world-famous sex symbol she could carry off things that were beyond me, I found Christopher touchingly oblivious to any difference between our circumstances. No, he insisted, Sylvia would like nothing better than to take me shopping.

Over the few days I spent with her we did not, thank God, go shopping, but we did talk. She was only mildly interested in me but she quizzed me a bit. After dinner once when I’d been speaking French she asked me rather sharply how old I was. Then she looked me up and down and said: ‘So young and so smart – but I think it’s better to be tall.’ It was said without malice in a tone of realistic appraisal by someone who had spent all her life weighing her own assets, working out how to deploy them and, perhaps, getting the answer wrong. She spoke at least four languages and was certainly smart. She was also funny in a faux naive way and would say things that made you wonder at first if she was witty or stupid, until she had said so many of them you realised she was witty, just not keen to appear so. That winter she was back with Hugo because her five-month marriage to the American millionaire Alan Turner had collapsed. She entertained us with accounts of its disastrous trajectory starting with the honeymoon, for which Turner had borrowed a friend’s house. Sylvia found it depressing with a lot of ‘dreary modern art’ which she had decided to cheer up by applying nail varnish to the pictures here and there. A subversive sense of humour turned out to be one of many things they didn’t have in common.

My initial relief about her appearance turned out to be ill judged as well as ill natured. I think Sylvia, at that stage in her life, found it amusing to look like a Dutch housewife who’d let herself go a bit. It was a role. When she wanted to look like a film star she could. It took a long time, there was a lot of hanging about before we went out anywhere, and some rushing in and out of the bedroom for more vodka, but when she was ready she was amazingly, traffic-stoppingly glamorous. She would quite often then decide she didn’t want to go out after all so we would stay home and eat at the kitchen table, like the three bears with a resplendent Goldilocks.

Sylvia and Hugo had a son, whom they called Arthur because they’d been reading The Once and Future King when he was born, and who lived mostly with Sylvia’s mother. When they had met Sylvia was a beauty queen. Hugo’s ex-wife Elly Overzier had also been a beauty in the style of Anita Ekberg, for whom she was sometimes mistaken, but when she got an offer to go into films Hugo’s left-wing writer friends were horrified and talked her out of it. Hugo was furious, he told me, and determined not to let Sylvia make the same mistake. By then the ageing enfant terrible of Flemish letters, he made a show of his cynicism rather as Sylvia flaunted her naivety. His was the more authentic performance. By his own account he was her benign Svengali, their relationship based on her wish that they should get married and his refusal to do so. Every so often they would have a row about it and she would go off with someone else. Then when that didn’t work out she’d come back to him.

Soon after our visit Hugo and Sylvia parted once more, this time pretty much for ever. I never saw her again. Hugo died in 2008. He had dementia and arranged to offend the Catholic Church one last time by opting for an assisted suicide, on Good Friday. Sylvia’s obituaries have dwelt on Emmanuelle. It was what she was known for, but she was also witty, intelligent, touching and of course tall.

Comments

One wonders what became of Arthur, the son.