Aids starts with the deaths. With the dying. At first there was only confusion, incomprehension. Bodies that quickly became unintelligible to themselves. Nightsweats, shingles, thrush, diarrhoea, sores that crowded into mouths and made it impossible to eat. A fantastically rare form of pneumonia. Dementia in men of twenty: brains that shrank and withered. Tuberculosis of the stomach, of the bone marrow. A cancer meant to be slow-moving, to manifest benignly in elderly men from the Mediterranean, which burrowed from the outside in: from marks on the skin, to the stomach and lungs. Non-human illnesses: men dying from the blights of sheep, of birds, of cats, diseases no man had ever died of before. Men dying in the time it takes to catch and throw off a cold: ‘One Thursday,’ David France writes in How to Survive a Plague, ‘sexy Tommy McCarthy from the classifieds department stayed out late at an Yma Sumac concert. Friday he had a fever. Sunday he was hospitalised. Wednesday he was dead.’

Later, there were tests. A virus detectable in the blood. You were ill, but you might not feel it yet. Might not know it yet, except you did. ‘A new class of lifetime pariahs’, Susan Sontag called them in Aids and Its Metaphors: ‘the future ill’. The artist and film-maker Derek Jarman remembered his HIV diagnosis, in 1986:

I thought: this is not true, then I realised the enormity. I had been pushed into yet another corner, this time for keeps … The perception that knowing you’re dying makes you feel more alive is an error. I’m less alive. There’s less life to lead. I can’t give 100 per cent attention to anything – part of me is thinking about my health.

There were jokes by now: ‘What turns fruits into vegetables?’; ‘What does gay stand for? – Got Aids Yet?’ The sex that had made illness the future became suspect. ‘The problem with sex is I get the feeling that I’m not even supposed to think about it,’ Oscar Moore wrote in his PWA (Person with Aids) column for the Guardian. ‘[I am] supposed to be beyond sex. The trouble is that sex is not beyond me.’ ‘My whole being has changed … Even with safer sex I’ve felt the life of my partner was in my hands,’ Jarman reflected. ‘I’ve come a long way in accepting the restraint. But I dream of an unlikely old age as a hairy satyr.’

To have the virus was not only to face up to your own impending demise, but to see it advance towards you over the bodies of your friends. Jarman made a note in his diary in April 1989: ‘Since autumn: Terry, Robert, David, Ken, Paul, Howard. All the brightest and best trampled to death – surely even the Great War brought no more loss into one life in just 12 months, and all this as we made love not war.’ In March 1992: ‘We talked of the people who died of Aids this week.’ ‘To say “A friend of mine just died” doesn’t mean anything any more,’ the historian Simon Watney said in 1994, but

that network is qualitatively and quantitively specific to how gay men live. Deaths in those networks mean deaths of whole areas of memory and association. Death for most heterosexuals means family deaths most of the time, up to the age of about sixty, and then it begins to mean friends. It’s so different for gay men in the epidemic. And you know there’s more to come and it’s going to get worse before it gets better, because you know so many people who are positive. Anyone living in metropolitan London is living that life around the clock.

‘I didn’t cry when Tim died,’ Moore wrote:

To be honest, I was relieved. He couldn’t see. He couldn’t hold his own cigarette. He could barely hold his own water. He knew I was there and he became flustered by my silence. But what can you say about your own life to someone on the brink of theirs? I didn’t cry when Philip died either. I’d seen him shrivel into a brown husk, the taut dry skin stretched over his skeleton like a mummified body excavated from some desert tomb. I’d seen him in his wheelchair with an oxygen mask clamped to his face, his eyes rotating wildly. I went to the loo and stared at my face and felt the dread creep up into my chest like frost, knowing that this could, maybe would, happen to me.

It did. Sickness on sickness on sickness on sickness, weakness on weakness, one hospital stay slotting neatly behind another, each documented and, seemingly, endured with impossible good cheer. Moore had shingles in his gut, Kaposi’s sarcoma, molluscum contagiosum, had always to carry two plastic bottles of medication in his pockets, each connected to a Hickman line. He had neuropathy in his toes, ‘numb and brittle as icicles’. His vision disintegrated, eaten away by herpes; he found himself on Charlotte Street, ‘totally helpless, knowing that if one person walked into me I was finished … I crept along, clinging to the wall, emaciated, etiolated, wrapped up in jackets and scarves and hat and feeling very conspicuously a PWA.’ At the end, he was almost totally blind: ‘I can hear the splash and swish of car tyres on wet tarmac outside my window and I can hear rain rapping like fingernails on the glass, but I cannot see across the room, let alone outside, into the street.’

It came for Jarman too: ‘The razor bumps over the bones of my face. Even the bones themselves have shrunk. My hands seem half their normal size. My raw stomach aches and aches.’ The journalist Simon Garfield interviewed him in 1993, for his superb (and predictably out-of-print) book on Aids in Britain, The End of Innocence:

Derek Jarman says he feels like an eighty-year-old man, not only old, but lonely, missing all his friends. Walking along Charing Cross Road towards Chinatown he holds a thin brown stick, too short for his needs … His new haircut means you can see more of his face, ruddy from drugs, dotted with small inflammations. At 51, he is a picture of wrecked beauty. One side of his mouth turns down, as if he’s had a small stroke. Four days ago he was in hospital, one of several recent visits, this time to fight pneumonia. Three days ago he was with a specialist trying to save the sight in his left eye; at the moment he can’t read. Every morning and evening he is on a drip. He refers to his body as a walking lab, pills slushing against potions in his insides.

Ten years earlier, Martin Amis had reviewed one of the first British documentaries about Aids for the Observer. Aids, he wrote, ‘is a visitation that makes you believe in the Devil’:

With Aids … it seems to be promiscuity itself that is the cause. After a few hundred ‘tricks’ or new sexual contacts, the body just doesn’t want to know any more, and nature proceeds to peel you open. The truth, when we find it, may turn out to be less ‘moral’, less totalitarian. Meanwhile, however, that is what it looks like. Judging by the faces and voices of the victims, that is what it feels like too.

Aids starts in the 1970s. Here’s Edmund White, describing the San Francisco gay ‘look’ in his travel book States of Desire (1980). Bodies made themselves intelligible:

A strongly marked mouth and swimming, soulful eyes (the effect of the moustache); a V-shaped torso by metonymy from the open V of the half-unbuttoned shirt above the sweaty chest; rounded buttocks squeezed in jeans, swelling out from the cinched-in waist, further emphasised by the charged erotic insignia of coloured handkerchiefs and keys; a crotch instantly accessible through the buttons (button one already undone) and enlarged by being pressed, along with the scrotum, to one side; legs moulded in perfect, powerful detail; the feet simplified, brutalised and magnified by the boots. For gay men there are three erotic zones – mouth, penis and anus – and all three are vividly dramatised by this costume, the ass the most insistently so, since its status as an object of desire is historically the newest and therefore the most in need of redefinition.

‘I sensed clothes might betray me, but to what?’ Jarman remembered. ‘Only when, at 22, I tumbled into bed with Ron did I become aware that in the pubs and bars there was a look, a cut of the trousers, a flick of the hair.’ Later

came the leather years, with a battered jacket rancid with Vaseline and poppers, and jeans split at the knees. Doc Martens, short hair again. Without this you could not get into clubs like the Mineshaft [in New York], where the doorman smelled you to make sure you weren’t wearing aftershave. In fact, so dark were the recesses of the Mineshaft all you could really do was touch and smell.

Ah, the Mineshaft. White wrote about it in States of Desire:

Through an archway is a large dim room. Along one wall in doorless cubicles couples stand and carry on. Elsewhere slings are hung from the ceiling; men are suspended in these, feet up as in obstetrical stirrups, and submit to being fist-fucked. One flimsy wall in the centre of the room is perforated with glory holes. Two staircases lead downstairs to still darker rooms, cold cement vaults. In one is a bathtub where naked men sit and wait to be pissed on … Since it is a place, not a person, it is morally neutral. What it offers are the props of passion, an arena for experiment, a stimulating dimness.

Oh, New York, New York! A regular told Garfield:

I had never seen anything like it: fist-fucking, racks, and the stench of piss and poppers and everything else and the heat and the men and the light was all red and I remember thinking standing there, adrenaline thundering round me and thinking: ‘This is evil, this is wrong.’ I remember being very frightened; it seemed so extreme. But later I was thinking about it a lot, and wanking when thinking about it, and the next thing I knew I was back there and within weeks it felt like home.

‘Anyone who lives with a lover chooses the comforts of repetition over the dangers of adventure,’ White concluded.

What good came out of the 1970s? I kept wondering. All the better a question now that we’re in the 1980s. Well perhaps sex and sentiment should be separated. Isn’t sex, shadowed as it always is by jealousy and ruled by caprice, a rather risky basis for a sustained, important relationship? … And we do in fact seem looser, easier in the joints, and if we must lace ourselves nightly into chaps and rough up more men than seems quite coherent with our soft-spoken, gentle personalities, at least we no longer need to be relentlessly witty or elegant.

‘For many gay men, fucking satisfies a constellation of needs that are dealt with in straight society outside the arena of sex,’ Richard Goldstein argued in the Village Voice in 1983. ‘For gay men, sex, that most powerful implement of attachment and arousal, is also an agent of communion, replacing an often hostile family and even shaping politics. It represents an ecstatic break with years of glances and guises, the furtive past we left behind.’

‘Gay men had as much use for condoms as for tampons,’ France notes. He quotes Joseph Sonnabend, one of the first clinicians to investigate Aids. ‘I think most gay men said: “Oh thank God, that’s one thing we don’t have to worry about.”’ In 1973, a gay bar in New Orleans was deliberately set on fire: 32 people died. No charges were ever filed. A few years later, a friend of White’s was shot and killed outside a gay bar on Folsom Street in San Francisco. The gun was fired from a passing car, never traced. ‘He was so big and proud and conspicuous that no doubt he made a fine target for free-floating homophobia.’

Aids starts in history. Jarman was born in 1942, 25 years before male homosexuality was legalised, under certain conditions, and only in England and Wales (Scotland had to wait until 1980 and Northern Ireland until 1982):

When I was young society seemed so totally restrictive I found that the time I did not spend on the piers or bath houses wasted. The heterosexuality of everyday life enveloped and asphyxiated me. I numbed myself to this life – something which all gay men and women do even if they bury the hurt of it.

Viewed from this angle, the 1960s weren’t so swinging:

Gay? Well we were still queer, with nowhere to go, just two or three unlicensed bars that held a hundred at the most; coffee bars with dance floors where you were forbidden to touch: ‘Now lads please, you know the rules.’ So you sipped lukewarm Nescafe in a Duralex glass cup and stared … Finding sexual partners was difficult and they were often transitory – hardly bothered to take their pants down before buttoning up. And the police might raid, send the prettiest ones in as agents provocateurs. They had hard-ons, but didn’t come. Just arrested you. Where was the party?

Where was the party? Jarman was a teenager in the 1950s, the most repressive decade for gay men in Britain: thousands were terrorised and arrested, with a thousand custodial sentences handed down each year. In total, more than 50,000 men were prosecuted under the ‘gross indecency’ clauses of the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act before it was repealed in 1967. But gay sex had – has – always been shadowed by threat, by violence, by shame and by death. In 1823 Thomas Buttle was indicted for ‘unlawfully receiving the naked private parts of a person in his mouth’; John Day for ‘permitting a person to handle [his] private parts naked’. In 1835 John Smith and James Pratt were spied through a keyhole having sex in a room in a lodging house on Blackfriars Road. ‘The detection of these degraded creatures was owing entirely to their poverty,’ the magistrate admitted. ‘They were unable to pay for privacy, and the room was so poor that what was going on inside was easily visible from without.’ They were the last men hanged for sodomy in Britain. On 7 August 1989, Jarman spent the day with a book called The Unacceptable Vice, which described the ingenious violence meted out to those caught indulging in it over the centuries: ‘Here the madness of Christianity can be followed in its fight against the physical body,’ Jarman wrote. ‘And when it was all ended who can show one soul saved for the thousands mutilated and murdered? A murderous tradition which still contrives to legislate against us.’ That ‘us’ included me, although at the time I was less than a month old.

The first time I had sex with a man, I lay awake for hours afterwards, thinking about Aids. Everything I didn’t know entered and filled the room; questions swerved through the darkness, fear coagulated on the sheets. Had we been safe? Was it ever safe? Was the whole thing a tightrope walk – tightrope fuck, even trickier – over the abyss? If I was ever taught about HIV, I don’t remember it, didn’t remember it then. Perhaps in sex ed, but since that was all about straight sex (or, as it was known, ‘sex’), it wouldn’t exactly apply. Section 28 was abolished at the end of 2003, when I was 14. We had one class discussion about homosexuality: our teacher held a vote on whether it was OK or not – of course some people voted that it wasn’t – and told us that he once had to leave a pub because two men nearby started kissing.

In the morning we talked about it, me and the man I’d had sex with; he explained the mechanics of transmission to me, told me I had nothing to worry about. (Lucky me, lucky him.) I was 21. I couldn’t stop worrying. But I couldn’t knock off the sex either. So, no matter how safe, no matter how minimal or risk-free, I would fret. Might I not have a nick somewhere? A scratch, here by my nail? What about the soles of my feet? Had my gums bled when I last brushed my teeth? There was the time I went to a gay sauna, reached deep into what I thought was the condom supply, only to discover it was the useds. Alcohol made it all worse. Why did I do that? Did I do that? Every time I had a cold, a sore throat, it foretold disaster. I would examine my tongue minutely in the mirror. Once, preparing a meal for friends, I cut my finger chopping vegetables into a stew – and poured the whole thing, still bubbling, into the bin. Negative test results were treated like suspended sentences.

No doubt I was an extreme case, though all the gay men I know have similar stories (recently, at the cinema watching 120 BPM, about the Aids crisis in Paris, my friend booked an HIV test halfway through). But what was I – what are we – panicking about, exactly? No one wants an avoidable chronic illness, but everyone knows that, in the West at least, HIV is now a manageable disease, making almost no difference to predicted lifespan; a doctor told me not long ago that you’d be better off with HIV than diabetes. But this is to take a purely medical view of something that has never been purely medical. I knew that if I contracted HIV I would survive, that my life would change but not be ruined, but this did nothing to negate my fear. It did not even blunt its edge. There is no miracle cure for shame, which is what I knew I would feel if I contracted the virus. I would be another gay man who went ahead and got HIV. It was a case of fear and shame: fear of shame, the sweat-sour shame of fear. I had never been taught about the Aids crisis; I had never read a book about it, or watched a film (not even Philadelphia), or had a conversation with my parents. I had no memory of consciously taking in a single formed idea about it. And yet the fear and the shame were there anyway, latent in me, in the whole culture, generationally transmitted. ‘Aids? That’s a forgotten disease, isn’t it?’ a heterosexual man in his fifties said when I told him I was writing this piece. ‘We’ll worry about you,’ my dad said to me when I came out. Two months after that, my cousin asked: ‘Have you got Aids yet?’

How should we write the story of Aids? Where should we start? David France and Richard McKay’s books are both in dialogue with Randy Shilts’s bestselling And the Band Played On, published in 1987, when an end to the story was impossible to imagine. France is closer to Shilts in his ambition to provide something resembling a total history of the crisis, though in fact both his and Shilts’s are deeply American books. There are important differences – France takes the view from New York rather than San Francisco, and, writing from the end of the crisis, is able to tell a more optimistic (‘happier’ would be the wrong word) story, focusing on the significance of Aids activism – but they are both written from inside the gay movement by gay men, and tell the story year by year as an unfolding drama, with a cast of recurring characters, to whose thoughts and conversation we are granted intimate access. They are not books specifically about the scientific and medical aspects of Aids, but the accounts they give are essentially scientific and medical, in that the narrative is structured around the relentless attack of the virus, as a mystery to be solved: the clock ticks, and the death count multiplies, and we see how the search to understand and treat HIV was impeded – by politics, by journalists, by squabbling and prejudice and injustice. France shows how these obstacles were partially overcome.

The problem with writing Aids as a mystery, though, is that anything might be a clue. The past falls under suspicion; blame hovers. Shilts was convinced that the enthroning of sex in gay life in the 1970s had created the conditions for the epidemic, which it had, in a strict sense – but did that really mean gay men had been ‘playing on the freeway’? It also led him to create a convenient villain, a young French-Canadian airline steward called Gaëtan Dugas, who was already dead when Shilts began writing his book. Dugas was identified as ‘Patient Zero’, a man whose sexual rapaciousness allowed him to spread the virus through the United States, and whose sense of sexual entitlement was such that he continued to infect individuals long after he understood himself to be a biological threat. This is a fiction that France quietly dismisses and which McKay demolishes in his meticulous account of its construction, in the process providing an alternative and complementary history of the early years of the crisis. The story they tell is not the only one that can be told – it makes no serious room for the epidemic as it manifested outside the US, in heterosexuals or in women or in people of colour, or for any exploration of its personal, cultural and political effects (on which Jarman in his diaries, reissued by Vintage, is consistently thoughtful and thought-provoking). Still, it is a story everyone should know.

The Aids crisis as it unfolded in America is an object lesson in the danger, the potential violence, inherent in organised prejudice. ‘I realise that rights for gays are not a big deal for most people – not terribly important in reforming a country,’ a man living in Chicago told Edmund White in the late 1970s – ‘unless you happen to be gay.’ The ‘Gay America’ that White toured for his book was concentrated not only in cities, but in what were still called ‘gay ghettos’. ‘One aspect of oppression,’ he wrote, ‘is that it tends to force gay singles to live in the city. No hardship on those of us who love urban life, but painful for those who hate it.’ In Portland, White discovered ‘an unusual degree of integration with the straight community’ almost touching in its banality, distressing for the same reason: ‘A gay single or couple must deal with the family next door and the widow across the street; the proximity promotes a mixed gay-straight social life – parties, dinners, bridge games, a shared cup of coffee.’ Homosexuality was still illegal in 25 states – in 1986 a couple who appealed against their prosecution under sodomy laws in Georgia lost their case in the Supreme Court – and the 1970s had ‘produced the fiercest round of anti-gay legislation the nation had ever known’: ‘suspicion of homosexuality was enough to block applications for security clearance, deny housing, defrock clergy members, fire schoolteachers, and bar foreigners from entering the United States, even as tourists.’ White reported from Texas:

Perhaps the biggest problem facing Houston gays is violence in the streets … The police ignore the danger; if they do respond to a call for help, they often arrest the gay victim on the charge of public intoxication, a vague measure that permits officers to harass anyone they choose … police brutality remains troublesome … Police raids on bars and adult bookstores are a familiar part of Houston gay life … As things stand, two men or two women usually cannot rent a one-bedroom apartment … and if someone takes an apartment on his or her own and then moves a lover in, both of them can be (and usually are) evicted.

A Newsweek poll in 1983 found that three-quarters of Americans claimed to have never knowingly met a gay person. Between 1973 and 1994, McKay writes, ‘two-thirds to three-quarters of American respondents agreed with the statement that sexual relations between two adults of the same sex were always wrong. These results peaked at 78 per cent in agreement in 1991.’ (The proportion of people in the UK agreeing with the same statement climbed from 50 per cent in 1983 to 64 per cent in 1987, only dropping below 50 per cent in 1995, when the proportion who thought it ‘not wrong at all’ reached a high of 22 per cent.) All the men caught up in the epidemic had endured homophobia by virtue of living in an aggressively heterosexual society, often in aggressively heterosexual families. The writer and activist Larry Kramer was told by his father that he wished he’d ‘shot [his] load in the toilet’; when France came out to his family, his father was baffled: ‘It’s like wearing shorts to show off a wooden leg.’ Other men revealed their gayness in the same breath as their HIV or Aids diagnosis, only to be punched or pushed out the door; for others it represented a second coming out, compounding their original sin, or reflecting on it. There were parents who refused to sit at bedsides, leaving their child to die without them, or were never told their child was dying, until their child was dead; and families who covered up the cause of death, inventing circumstances they were not ashamed to relate, which didn’t involve saying the word ‘Aids’.

Not that it was called Aids at first. At first it was ‘gay cancer’ – the inexplicable appearance of Kaposi’s sarcoma, with its distinctive skin lesions, in scores of gay men around 1979-80 – then Grid (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), and then, in mid-1982, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. The US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention started to track it, and to assess the size of the epidemic: in December 1981 there were 152 cases in 15 states; by the summer of 1983, there were 2224 cases in 33 states, 891 of whom were already dead; by the summer of 1984, there were more than 5000 cases spread across nearly every state, 2300 of whom were dead; by the summer of 1985, there were more than 12,000, with more than 6000 dead. By the spring of 1987 a total of 51,000 cases had been reported worldwide, across 113 countries. Here was a plague. US police put on gloves and surgical masks to arrest anyone they suspected of having the disease. In San Antonio, Shilts writes, ‘paramedics demanded their own protective suits – consisting of a hospital gown, pullover hood, surgical mask and shoe covers.’ A Florida hospital paid $14,000 for a private jet to fly an Aids patient to San Francisco, where he was dumped without prior warning and later died. Of all the hospitals in New York, only the NYU Medical Centre openly accepted Aids patients, and even there they were denied admittance to shared rooms.

The NYU School of Medicine, the Beth Israel Medical Centre and Columbia Presbyterian all refused to perform dental work on Aids patients. Only one funeral home in New York, established at the time of the Spanish flu, was prepared to take the Aids dead. People with Aids lost their jobs, their health insurance; they were evicted from their homes. A man robbed a bank by passing a note to a cashier: ‘I have Aids, and I have less than thirty days to live.’

In the UK, as in many other countries in Europe, Aids was initially considered an overseas ‘media import like Hill Street Blues’, in Garfield’s words. The gay charity Switchboard assured nervous callers that ‘sex is as safe as crossing the road.’ When Terrence Higgins collapsed at work and began inexplicably dying in a London hospital in July 1982, his boyfriend suggested to doctors that ‘maybe it was this American thing,’ but was politely ignored. By May 1985 there were 140 reported cases. The tabloids went into overdrive: ‘Scared firemen ban the kiss of life in Aids alert’; ‘Aids: now ambulance men ban kiss of life’; ‘Policeman flees Aids victim.’ In the early days, Michael Adler of Middlesex Hospital remembered,

it was very difficult to get them hospitalised, it was very difficult to get patients treated as normal human beings. People were frightened, they thought it was contagious, the patients had to be put in side wards, you couldn’t get the domestic staff to go in, you couldn’t get the porters to go in. We treated people extremely badly. It was like medicine six hundred years ago.

Tony Pinching, a consultant in clinical immunology at St Mary’s, took one of his first Aids patients to a case presentation:

he came in, and I can still hear the drawing in of breath, the hush that descended. Here was the moment of reality for that audience; this wasn’t just a strange disease that we read about in the journals with a strange sort of people who do bizarre things. This was an ordinary bloke, you could have met him anywhere, and he was terribly straightforward.

Gaëtan Dugas, the French-Canadian air steward, was interviewed by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in mid-1982 for a study that hoped to shed light on how the illness was transmitted. In June that year a landmark cluster study in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report had found sexual links between nine of the 26 first reported cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) – then the most typical indicators of Aids – in gay men in southern California. Four of these men had mentioned that they or their acquaintances had had sex with Dugas between nine and 18 months before they developed symptoms. Dugas was one of the earliest patients to be diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma, in late 1979. He gave the CDC investigators the names of 72 men he had slept with in a number of US cities, carefully recorded in address books, nearly 10 per cent of the 750 he estimated he’d had sex with in the last three years. This made him far more helpful than the other ill gay men he was later connected with in the expanded, nationwide cluster study the CDC produced in 1984 – of whom 65 per cent reported more than 1000 lifetime sexual contacts, and 75 per cent more than 50 in the year before they experienced symptoms, but none of whom were able to produce anything like as many traceable names.

Dugas died in March 1984, aged 31, shortly before the publication of the cluster study that made him, in McKay’s words, ‘the most demonised person with Aids of all time’. The study’s intention was to develop the hypothesis of the first cluster study, that Aids was sexually transmitted. Dugas, as a patient from outside California who was connected to the original cluster group, and who, exceptionally, was able to provide detailed information about his sexual history, made it possible for the investigators to map a total of forty cases in several cities. They did not believe that he was the ‘origin’ of the disease, but he was situated at the centre of the cluster diagram, a reflection of his ‘arbitrary status’ as the individual with the most identifiable contacts, which nonetheless implied that the links between him and other cases represented a ‘web of transmission’. Astonishingly, the ‘Patient Zero’ label was the result of a simple typographical ambiguity, though its ready take-up in both scientific and lay communities attests to what McKay calls ‘a broad societal need to imagine and then seek a simple explanation and source for complex patterns of contagion’. Dugas was identified in the study as ‘Patient O’ – the letter stood for ‘Out of California’ – but people reading and discussing the research began referring to and thinking about a ‘Patient Zero’.

One of the many people who misunderstood the research was Randy Shilts, who interpreted the cluster diagram as showing ‘a sort of closed sexual network with infection radiating out from the centre’, so that in And the Band Played On he could state, entirely incorrectly, that ‘at least 40 of the first 248 men diagnosed with Grid in the United States … either had sex with Gaëtan Dugas or had had sex with someone who had.’ Shilts, in his own words, became ‘obsessed’ with Dugas, and increasingly angry. He met Paul Popham, the founding president of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and one of Dugas’s former lovers: ‘I realised that Paul, who had visible lesions on his face, was dying from a virus from this guy. It was like I was seeing the legacy of this person and his virus.’ In January 1986, Shilts made a sketch of Dugas’s chief characteristics in his notepad: ‘big dick, handsome, blond, slim, wounded puppy faces, brought tremendous empathy, seductive in movements, spe[e]ch, affect, could get anyone he wanted’. The note concluded: ‘take home, after sex, turn on lights, “see these bumps. I’ve got gay cancer.”’ The notion of Dugas as a sexy, sex-mad sociopath who brought Aids to the US and, after he knew he was ill, deliberately continued to infect men – the reveal after the lights going up a chilling piece of theatre – became central to the promotion of Shilts’s bestselling book, and to Dugas’s posthumous international notoriety as ‘Patient Zero’, defined in one leading medical dictionary for nearly two decades as the ‘individual identified by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention as the person who introduced the human immunodeficiency virus in the United States’. The National Review called him the ‘Columbus of Aids’.

He wasn’t. Not only did the 1984 cluster study present Dugas in a false light from the start; once the incubation rates of HIV were better understood it became clear that the whole thing was based on false premises. The typical length of time between HIV infection and an Aids diagnosis is now recognised to be between ten and fifteen years (though it can happen much sooner if you are very young, or old, or otherwise vulnerable), with some HIV-related symptoms usually developing after five. The early assumption was of an incubation period of around 18 months. The 26 California cases should never have been interpreted ‘as the 26 first cases of infection, in absolute terms, caused by the transmissible agent that would subsequently be identified as HIV’. There should never have been any assumption that Dugas was responsible for infecting any of the men in the study, in any part of the country – the likelihood is that they were all infected already, as he was.

McKay also tears down the second part of the ‘Patient Zero’ myth: that Dugas was a sociopath. If Dugas continued having sex after his diagnosis – which McKay thinks is likely – he wasn’t acting on evil impulse. (As for the ‘I’ve got gay cancer, and now you do too’ stories, McKay dismisses them as rumours, fanned by paranoia and collective trauma.) In the early panicked years of the epidemic, also the last years of Dugas’s life, gay men were given huge amounts of conflicting information about why they were ill, what they were ill with and whether they might get better. It seems that Dugas distinguished himself from the men who succumbed quickly to pneumonia, and was a believer in the ‘immune overload’ theory of Aids, popular until the HIV virus was isolated in 1983-84: its proponents held that Aids was the result of an immune system depleted by repeated bouts of sexually transmitted infection – the gonorrhoea, herpes and intestinal bugs that had been accepted as part of an active gay life – and that a slow recovery could be made by limiting partners and taking precautions. In short, that Aids wasn’t something that could be transmitted at all. ‘In the absence of treatment, or even certainty about whether Aids was rooted in an environmental, infectious, or genetic cause,’ McKay concludes, ‘the easiest answer to provide – stop having sex – was often the most difficult for many people with Aids to put into practice.’ If there’s a fate worse than death, it might just be never to have sex again, and die anyway.

‘The problem remains,’ Sean Day-Lewis wrote in the Daily Telegraph in 1982, ‘that Aids, or the “Gay Plague”, is not limited to active homosexuals.’ In both the US and the UK (which bought up to 60 per cent of its Factor VIII, a clotting agent used to treat haemophilia patients, from America), the authorities were painfully slow to pick up on the threat to the integrity of blood transfusion services posed by the developing epidemic, even after it became clear that a blood-borne agent was likely to blame. The first concrete evidence of a child being infected through a blood transfusion in the US was published in late 1982 – the signal, France notes, for ‘a torrent of anti-gay violence the likes of which the community had never seen before’. But blood banks, fearing a backlash and unwilling to destroy their products, continued to downplay the risk. Tens of thousands of haemophiliacs and transfusion recipients were infected in the US before some limited controls and screening procedures were established in March 1983. In the UK, where screening of blood donations wasn’t introduced until late 1985, at least 1200 haemophiliacs were infected. The Daily Express called them the ‘Aids Innocents’: ‘They have led blameless lives and it could never be said that they have brought the tragedy on themselves.’ By this time it was also known that intravenous drug users (guilty) were a high risk group, that women who slept with bisexual men or drug users (innocent-ish) or worked in prostitution (guilty) could be infected, as could the heterosexual men (innocent) who slept with them, and that babies (innocent) could be born ‘future ill’. Susan Sontag observed of the epidemic in Africa – the WHO estimated 301,861 cases on the continent in 1993, undoubtedly a serious underestimate – that

if Aids had remained only an African disease, however many millions were dying, few outside Africa would be concerned with it. It would be one of those ‘natural’ events, like famines, which periodically ravage poor, overpopulated countries and about which people in rich countries feel quite helpless. Because it is a world event, which afflicts whites too, and because it affects the West, it is no longer a natural disaster. It is filled with historical meaning.

There was always a tension between the pervasive fear of Aids – that anyone might catch it, perhaps from a blood transfusion or from healthy hetero sex, but also from a kiss, or a sneeze, or a toilet seat – and its casting in moral terms. In 1986, the British government sent out a leaflet to every household in the country stating that Aids ‘is not just a homosexual disease’ and that it could be passed ‘from man to man, man to woman and woman to man’. It encountered fierce criticism. The chief rabbi wrote to the health secretary, Norman Fowler: ‘Say plainly: Aids is the consequence of marital infidelity, premarital adventures, sexual deviation and social irresponsibility.’ Fowler later remembered that Margaret Thatcher’s ‘initial instinct was that this was not a big problem, and at any rate the people who get Aids, it’s entirely their fault, their responsibility and we shouldn’t spend a lot of time on it’. When Ronald Reagan broke a seven-year silence and spoke publicly about Aids for the first time in 1987, he asked: ‘After all, when it comes to preventing Aids, don’t medicine and morality teach the same lessons?’

In truth, the tension between the fear that ‘everyone’ was at risk of Aids, and the conviction that only the ‘guilty’ were, was not a tension at all: it was an opposition instrumentalised by governments that needed to be seen to be fighting Aids but didn’t want to seem overly relaxed about the sorts of people who actually had it. When Bill Clinton’s administration finally developed the first ever federally funded safe-sex campaign promoting condom use in 1994, the accompanying TV campaign featured only heterosexual couples. Gay groups that played up the ‘equal opportunities’ narrative of Aids, as a means of challenging stigma and attracting support, soon came to feel that it was a mistake. In Britain, where 75 per cent of all Aids cases were in gay men, the director of the Terrence Higgins Trust found that ‘the button you had to press to get more money was the one labelled “everyone is at risk.”’ An obvious fact was forever being obscured. As Jonathan Mann, the founder of the Word Health Organisation’s Global Programme on Aids, told a London audience in 1993,

the spread of HIV is strongly determined by an identifiable societal risk factor … the scope, intensity and nature of discrimination which exists within any society … Ask yourself … who was discriminated against in my community and my country before Aids came? And then ask yourself: are those people receiving their appropriate share of Aids programme information, services and support?

‘The proliferation of Aids through the East Coast corridors of poverty,’ Shilts wrote, ‘heralded the start of the second Aids epidemic in the US, distinct from the epidemic in gay men.’ Urban poverty, intensified by Reaganomics, coupled with the burgeoning crack and heroin epidemics, offered fertile ground for HIV transmission (as it did in Edinburgh under Thatcherism). As early as January 1985, the majority – 54 per cent – of New York’s Aids cases were non-white, and by 1988 so were the majority of the newly diagnosed in the US as a whole. When conservatives began complaining that it wasn’t true to argue and act as though the ‘general population’ was at risk, Sontag pointed out that ‘the “general population” may be as much a code phrase for whites as it is for heterosexuals. Everyone knows that a disproportionate number of blacks are getting Aids, as there is a disproportionate number of blacks in the armed forces and a vastly disproportionate number in prisons.’ The gay writer Jon-Henri Damski pointed out that Dugas was alleged to have caught the disease from an African man in France: ‘That makes Africans and blacks less than zero.’

The answer to Mann’s second question – were the people discriminated against before Aids came now receiving their appropriate share of Aids support? – is of course no. ‘The bitter truth,’ Shilts wrote, ‘was that Aids did not just happen to America – it was allowed to happen.’ The victims, by being who they were, were a source of embarrassment and difficulty, if not the object of outright hostility. Shilts was right that the disease was fundamentally understood as a ‘gay’ one, even when other facets of the epidemic quite quickly revealed themselves: ‘Patient Zero’ helped all that along. (Much of the shame felt by heterosexual PWAs was shame billeted from another place, shame by association.) And if anyone was absolutely guilty, could not be said to be ‘blameless’, it was the gays. ‘The infection’s origins and means of propagation excites repugnance, moral and physical, at promiscuous male homosexuality,’ declared the Times in 1984. Squeamishness about sex – especially gay sex – bedevilled responses to the crisis. ‘Bodily fluids’ was the preferred term for semen and vaginal secretions, but it was vague enough to be thought to encompass saliva, for example, which allowed anxieties about contamination by coughing or spitting or kissing or sneezing to perpetuate themselves. In Britain, Thatcher balked at the prospect of a national newspaper campaign about Aids; when pushed, she revealed a preference for sticking notices on the backs of toilet doors, like the warnings about VD in the 1950s. Defeated on this, she then intervened to remove the sections of text explaining why anal sex increased the risk of transmission, instating instead a prim reference to ‘rectal sex’ and ‘sheaths’. Later, she shut down attempts to organise a national questionnaire about British sexual habits. The Aids leaflet was rewritten at the last minute: the words ‘penis’, ‘anus’ and ‘back passage’ were removed.

Most of the US media was no better. It took two years and nearly six hundred deaths for Aids to reach the front page of the New York Times, which refused to use the word ‘gay’ and had a policy of not referring to homosexual partners in obituaries. One study found that the San Francisco Chronicle, in contrast, by covering the disease in detail, had a palpable impact on health education, and put political pressure on the relevant local authorities to develop an adequate response. ‘In the [first] thirty months of plague,’ France writes, ‘a time in which 1340 New Yorkers were diagnosed and 773 were already gone,’ the administration of the New York mayor, Ed Koch, almost certainly a closeted gay man, ‘had spent just $24,500 on Aids. In the same time frame, San Francisco had allocated and spent more than $4 million on care and prevention.’ San Francisco had 12 per cent of the national caseload, as opposed to New York’s 42 per cent. Koch’s money had gone to support a care in the community programme set up by the Salvation Army; it was cancelled after 15 months, with seven people enrolled. It turned out the phone lines had never been installed.

The most obvious beneficiary of the media’s lassitude was Ronald Reagan. The US government repeatedly dragged its feet when it came to Aids policy, when it wasn’t standing still or attempting to walk in the other direction. The administration proposed cuts to health spending as the epidemic gained momentum: for the fiscal year ending in 1984, Shilts pointed out, ‘the entire National Institutes of Health had proposed spending only $9.4 million on Aids, or about two tenths of 1 per cent of the agency’s budget’ – though Congress voted for more funds. In 1986, the government planned a 10 per cent reduction in Aids spending. In 1987, it wanted a 22 per cent cut, a drop of $29 million. By then, hundreds of thousands of Americans had been infected with HIV, 36,058 had been diagnosed with Aids, and 20,849 had died. The US was the only major Western government without a co-ordinated education policy on Aids: the administration couldn’t brook any federally funded guidance on ‘safe sodomy’. It also officially prohibited HIV-positive people from crossing its borders, a ban that only expired in 2010: in January 1992, about to visit New York, Jarman was advised by his doctor to take his medication out of its packets, to avoid detection. In 1987 Reagan appointed a presidential commission on the epidemic, composed of cronies and cranks ‘whose lack of experience was matched by their reckless beliefs’, France writes: it included a New York cardinal, a supporter of quarantine laws for PWAs, and a proponent of the toilet seat theory. When, against the odds, and thanks to the unforeseen (even by him) leadership of James Watkins, a retired admiral, the commission produced a wide-ranging report of 576 recommendations, one of which was to triple the federal budget to $20 billion (‘seven tenths of 1 per cent of the defence budget’), Reagan ignored it.

In Britain, after an initial spurt, overall funding for the war on Aids was gradually reduced. Benefits cuts disadvantaged PWAs, who had multiple strands of income bundled into one flat sum, which would increase, Garfield notes, only if they ‘could reasonably be expected to die within six months’. The Aids brief passed from the health secretary to a junior minister in the Lords. Aids education, placed on the national curriculum in 1987, was removed by 1993. Section 28 was passed in 1988: by preventing local councils from ‘promoting’ homosexuality and banning the teaching in schools of the ‘acceptability’ of homosexuality as a ‘pretended family relationship’, it turned silence into a weapon. And, as a new generation of gay activists was beginning to argue, Silence = Death.

‘We wished the worst for poor Rock Hudson,’ David France admits. ‘We had also wished catastrophe for Pope John Paul II and Ronald Reagan, both of whom had received blood transfusions after foiled assassination attempts recently. We prayed for a day when the disease struck someone who mattered, prayed for a weaponising of Aids.’ Hudson’s death, in October 1985, did make a difference. His old friend Ronald Reagan increased the Aids budget by $40 million in response. Hudson made Aids ‘respectable’, according to the philanthropist Wallis Annenberg, speaking at a starry benefit held in his honour. It didn’t last; and besides, it was a strange sort of respectability. Hudson had lived his life in the closet and hidden his condition until shortly before his death, vigorously denying rumours that turned out to be true. He had flown regularly to Paris for experimental treatment denied to his fellow citizens at home.

To be heard, you had to be dead, and a movie star, and a friend of the president. Michael Callen, a prominent Aids activist, summed up the condition of the average gay man in America in the 1980s: ‘sick, shunned, frightened and frightening; and largely unprotected by either law or popular opinion’. Larry Kramer wrote a piece for the New York Native in March 1983, entitled ‘1112 and Counting’ (that was the number of Aids deaths to date):

If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you we’re in real trouble. If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get … Unless we fight for our lives we shall die. In all the history of homosexuality we have never been so close to death and extinction before. Many of us are dying or dead already.

Kramer, along with Edmund White, was one of the founding members of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, established in New York in January 1982 as the first non-profit organisation responding to the epidemic, and the model for many others. (In a sign of the times, its first president, Paul Popham, was in the closet.) Its work included organising a helpline, fundraising, distributing informational literature and, France goes on:

creating a network of ‘buddies’ to visit the sick at home and help with chores; setting up therapy groups, legal clinics, and financial workshops demystifying the welfare system; arranging multiple ‘open forums’ for keeping community members up-to-date about fast-breaking developments; investigating and exposing improper hospital care; and training and fielding a small army of ‘crisis intervention counsellors’ to comfort all patients immediately upon their diagnosis, wherever they might be.

This wasn’t a community used to sympathy; it didn’t get much. ‘Every contact with the system is a confrontation,’ one volunteer said.

Callen and Richard Berkowitz were both diagnosed in 1982 with what was still being called Grid. They were patients of Joseph Sonnabend, a specialist in infectious disease once responsible for sexual health at the New York Department of Health, who now ran a general practice for gay men in the city. He was a proponent of the ‘immune overload’ theory and, under his influence, Callen and Berkowitz became advocates of ‘safe sex’ – ‘Two major sluts like us,’ Callen said, ‘are just the ones to do it’ – and self-published How to Have Sex in an Epidemic in June 1983, which was covered by the New York Review of Books and became an underground success. ‘Overnight,’ France writes, ‘in gay neighbourhoods around the country, rubbers took off’ – or went on – ‘as fast as Madonna’s debut album.’ Gonorrhoea diagnoses dropped by 73 per cent in San Francisco and more than halved in New York. It is likely that thousands of HIV infections were averted. But for more than half of all the gay men in both cities it was already too late.

In the early summer of 1983, Callen was invited to give congressional testimony:

On the whole, I believed in democracy. I believed in America. I felt it would only be a matter of time before education and the de-stigmatisation of gayness would bring me my rights. But now I am fighting for my life. I am facing a life-and-death crisis that only the resources of the federal government can end, and I am shocked to find how naive I’ve been. Not only is my government unwilling to grant my right to love whom I choose, my right to be free from job discrimination, my right to the housing and public accommodation of my choosing. This same government – my government – does not appear to care whether I live or die … You can be sure that ten, five, or even one year ago, I could not have imagined the possibility that I … would be up here begging my elected representatives to help me save my life. But there you are. Here I am. And that is exactly what I am doing.

A few weeks later, he was part of a group that stormed the stage at a conference of lesbian and gay health workers in Denver, and read out the 11 points of what became a manifesto for the rights of people with Aids. Some of the points were for ‘all people’: everyone should be offering support ‘in our struggle against those who would fire us from our jobs, evict us from our homes, refuse to touch us or separate us from our loved ones, our community or our peers’. The others were for PWAs themselves: that low-risk sexual behaviours should be preferred, that they deserved ‘as full and satisfying sexual and emotional lives as anyone else’ and to receive ‘quality medical treatment and quality social service provision without discrimination of any form’. There were also a series of more precise demands, that foreshadowed the world to come: PWAs should be ‘involved at every level of decision-making and specifically serve on the boards of directors of provider organisations’, ‘be included in all Aids forums with equal credibility as other participants, to share their experiences and knowledge’ and be entitled to ‘full explanations of all medical procedures and risks, to choose or refuse their treatment modalities, to refuse to participate in research without jeopardising their treatment and to make informed decisions about their lives’.

The Denver Principles marked a shift towards a new form of activism, one that put pressure on the scientific and medical establishments on which the wreck or rescue of so many lives depended. Most gay men’s lives were now fundamentally oriented in this direction, whether as patients, or as lovers and friends. For those who were ill, with a barely understood disease, expectations of what constituted healthcare were turned upside down: ‘we are all white rats in one laboratory or another,’ one New Yorker wrote in 1982, ‘being tested, probed, and monitored.’ More than ten years later, it was still possible for the singer Holly Johnson to tell Simon Garfield:

You go to these doctors and basically they don’t know a fuck! They just don’t know a fuck. Really! And they’ll admit it even, if you press them. They say, ‘Yes, we know a bit about treating the symptoms, but really we don’t know.’ And more and more you feel a bit like a guinea pig. The huge dilemma for a person with Aids is, do I take the fucking drugs, or don’t I bother? Am I going to die anyway?’

It wasn’t that there had been no progress at all. On the contrary, there had been a series of major breakthroughs, especially between 1984 and 1986. In 1983 and 1984, labs in Paris and Bethesda in Maryland, led by Luc Montagnier and Robert Gallo, had succeeded in isolating the retrovirus that caused Aids: ‘a pear-shaped particle with a dense and very black core at its centre, entirely unlike anything ever seen’. It was established that the virus could be transmitted via semen, vaginal fluid and blood. After entering an individual’s bloodstream and cells, it replicated and mutated extremely rapidly, before antibodies had time to develop; once they did, it was too late: the virus began gradually but inexorably to destroy the T-cells on which the body relies for the operation of its immune system. After an unseemly squabble between Montagnier and Gallo about who got there first (it turned out that Gallo had made his ‘discovery’ in a sample sent from Paris), the virus was named HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) by a mediation committee. Gallo went on to develop a test, which was available in multiple countries by 1985. Doctors in England were told that ‘positive results are expected to be very rare.’ The scale of infection there, as everywhere else, far exceeded expectations. It became clear that the incubation period was much longer than had originally been hypothesised, bringing home the full horror of what was to come: the epidemic would be like ‘different marathons begun at differing times’, in Shilts’s metaphor, and so far only the first, smaller group of runners, those who had been infected in the early to mid-1970s, had reached the finish line.

But there progress seemed to halt. In early 1987, the first drug licensed for use in treating patients with HIV for their underlying condition became available. AZT was believed to prevent the virus from replicating itself. Its early Phase II trials had followed the traditional method: half the cohort was given AZT, and the other half a placebo. The trial was abandoned when, after only a few weeks, 23 of the placebo group had died, compared to only three of those on AZT. The surviving placebo recipients were then put on AZT too, and showed remarkable improvement. There were still several causes for concern: AZT was extremely toxic, with a daunting list of side-effects (so toxic that many Aids patients would later be unable to take it safely); it was also time-limited in its effects, seeming to peak in usefulness after four months. But these were not enough to prevent it being rushed into production, with a bare minimum of clinical testing. The demand for the life-extending – life-saving? – treatment was huge.

The company behind AZT, Burroughs Wellcome, had made a deal with the US’s publicly funded National Cancer Institute that they would provide promising drug compounds (AZT was one) so long as the NCI did the screening of live retrovirus samples and carried out and paid for the human trials. In other words, they had done the minimum amount of work possible. No matter. At the same time as information about the success of the human trials was released, Burroughs Wellcome was listed on the London stock market. When the drug became available in America, it was marketed at $10,000 for a year’s supply, ‘more than any other drug in history’, according to France. ‘Few people without insurance could ever hope to swallow an AZT capsule,’ he goes on. ‘And the insured were not always better off. Many policies had annual or lifetime caps well below that figure.’ Wellcome’s share price climbed from £3.74 in February 1987 to £7.24 in November 1989, to £8.10 in 1993; its pre-tax profits were up 28 per cent at £283 million in 1989, and stood at £505 million four years later.

In both the UK and US the majority of funding was rerouted into further research on AZT’s use and development. Not only were other potential treatments for the virus neglected; there was an even more troubling failure to focus on the drugs capable of treating the secondary conditions that Aids patients actually died of: 24 opportunistic infections accounted for 90 per cent of all deaths. The biggest killer was pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: an effective prophylaxis, a drug called Bactrim, existed, but its use wasn’t recommended to doctors because there hadn’t been a large-scale trial; the use of an aerosol version of a drug called pentamidine, administered directly into the lungs, had also been found to be effective, but the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wouldn’t license it, again because there had been no large-scale trial. No trials were planned. People went on dying.

‘Drugs into Bodies’ was the rallying cry of Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power), founded in New York in 1987. (It soon had spin-offs across the US, as well as in London and Paris.) Larry Kramer, who was shortly to discover he was HIV positive himself, was once again a driving force: the new group was a supercharged version of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, more oriented towards storming the medical-scientific establishment and more politically assertive. France went to its meetings, and his account is at its most thrilling when it tracks the group’s activities and personalities.

Act Up staged demonstrations outside the Democratic Party Convention, outside the FDA, inside the offices of Burroughs Wellcome, on the trading floor at Wall Street, inside St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, outside the White House, at the International Aids Conference; a gigantic condom (‘unsafe politics’) was stretched over the home of the Republican senator Jesse Helms, who repeatedly sponsored homophobic legislation. Their pink triangle logo and ‘Silence = Death’ motto were instantly recognisable. And they had a nice line in slogans:

America

Isn’t

Doing

Shit

Publicity was wielded, sometimes bluntly, in the pursuit of specific policy aims. Burroughs Wellcome was shamed into reducing the cost of AZT: by 20 per cent in December 1987, which still left it as the most expensive drug in the US at $8000 a year, and then by a further 20 per cent in September 1989, so that at $6500 a year it finally reached the price range demanded by Act Up.

At the same time, Act Up, through its T&D (Treatment and Data) Committee, almost entirely constituted of autodidacts, experts in their own infinitely complicated disease, developed a detailed agenda for reform. It wanted an end to drug trials that used placebos, as well as to trials that demanded patients give up any other drugs they might be taking (including even prophylaxis against PCP). In the middle of an epidemic, with no cure in sight, standard clinical practice had become ‘tantamount to premeditated murder, no more ethical than denying patients food’, in Sonnabend’s opinion. With options so limited, and with death the only alternative, drug trials were healthcare, as another Act Up luminary, Jim Eigo, liked to put it. The failure to run trials involving large numbers of women and people of colour was abhorred as ‘medical apartheid’. Act Up also wanted more drugs trials; many, many more. In 1988 they discovered that 83 per cent of the Aids patients enrolled in trials were involved in studies evaluating AZT; only 25 people were enrolled on trials evaluating other drugs. In the absence of alternative licensed treatments, Callen and Sonnabend had in 1987 helped establish the PWA Health Group, which privately manufactured and sold a promising compound called AL721, reported to have a positive effect on T-cell counts. By the end of 1989, $2 million worth of the compound had been sold: ‘That’s $2 million worth of desperation and frustration,’ Callen said. ‘Buyers Clubs’ sprouted all over the world. Aids patients were losing a race against time. The normal rules couldn’t apply.

‘We have educated ourselves, we know more than the system knows,’ Kramer told the International Aids Conference in 1989. ‘And somehow we have to make the system listen to us so that your sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, and all of us may live.’ Act Up sought to short-circuit the drug licensing process by infiltrating the system. They demanded to be allowed to attend meetings of the Aids Clinical Trials Group, or ACTG (a body, Mark Harrington of the T&D Committee said later, ‘in which Burroughs Wellcome behaved as the majority shareholder’); they gained the right to speak at FDA advisory committees, and to present research produced by Aids patients and activists. The strategy began to pay off. In May 1989, the FDA licenced DHPG, which had been found to prevent Aids-related blindness, without a formal trial and despite having previously refused to do so. It also accepted the conclusions of a trial into the use of aerosol pentamidine as a prophylaxis for PCP carried out by Sonnabend and his Community Research Initiative, another first. Soon 250,000 people were on the medication. (Some things stayed the same: the manufacturers of pentamidine, Lymphomed, immediately raised the price.)

At the start of the new decade, Act Up raised its sights:

We assert that in any society worthy of the name humane, healthcare would be a right, not a privilege; that all people living within the borders of the USA are entitled to their government’s protection against disease and death; that treatments for deadly diseases should be developed for public health and not for private profit; and that the Aids communities must play a guiding role in the planning and execution of a co-ordinated, national effort to end the HIV epidemic and save the lives of all those infected.

That France refers to this as a ‘somewhat utopian flourish’ shows quite how low his expectations still are. There were more victories to come:

Bethesda in 1990 was like Berlin in 1989. Activists found that all the barriers at the NIH and the FDA vanished in a blink. Act Up members were appointed to dozens of subcommittees, not only to review the results of studies but to approve the studies’ designs and to help set priorities for which drugs to investigate and in what populations.

They had conquered. But the closer they came to power, the more frightening it got: ‘There was no guiding agenda, there was no leadership, there was no overall strategy for how to deal with Aids,’ Harrington remarked. ‘It sort of felt like reaching the Wizard of Oz. You’ve gotten to the centre of the whole system and there’s just this schmuck behind a curtain.’ And there was still no cure; not even effective treatments for the majority of the opportunistic infections killing Aids patients. In 1990, despite its recent successes,

Act Up was numbed by loss and exhausted from a frantic schedule of activism … On every front, the country remained stubbornly indifferent to the epidemic and its targets. While Congress approved a record $800 million for treatment and prevention in the country’s hardest-hit areas, not a dime was ever released. Hospitals in every major city were full to overflowing. Research was as chaotic as ever. Drugs that the NIH had called promising in 1985 remained untested five years later. The co-ordinating bodies were in disarray.

Meanwhile, the epidemic was gathering pace: in America, there was a new HIV diagnosis every minute, and four Aids deaths an hour. By 1991, 100,000 Americans had died of Aids, double the number killed in Vietnam. A further 42,000 US deaths were predicted for 1993, 50,000 for 1994. In 1993, the WHO reported 110,000 Aids cases in Europe, a massive underestimate (only 132 cases were claimed in the Russian Federation); over half of them were already dead. In the same year, the Concorde study into the effectiveness of AZT, which followed nearly two thousand patients from England, France and Ireland over a three-year period, reported its conclusions: the drug that had for years dominated research agendas and blotted horizons for Aids patients, swallowed up the vast majority of public funding and produced enormous profits for Burroughs Wellcome, made no long-term difference to survival. Concorde, in defiance of Act Up principles, had maintained a placebo cohort: these patients were more likely to have survived the three years of the study than the ones taking AZT. It was a devastating discovery. It showed that Act Up had been right to protest at the focus on AZT to the exclusion of other drugs, but it also suggested that their emphasis on fast-tracking drugs to market (to the possible advantage of pharmaceutical companies selling little more than fresh hope) and avoiding control groups at all costs was mistaken. It also made an end to the epidemic seem much further away. Act Up had in the meantime broken up: its activist and research wings parted ways, with the chastened T&D Committee turning itself into a think tank, the Treatment Action Group. In an epilogue to the paperback of his book, printed in 1995, Garfield ended on a miserable, angry note:

Surveys of young people suggest that Aids is a problem of the 1980s. Voluntary organisations report that the general public are less willing to donate money. Every month there are stories in the gay press of ‘slippage’, of the previously responsible succumbing to unsafe sex. Every week there are more funerals, more memorials. And each day clinics dispense more bad news to young men and women, but mostly men.

The end of the Aids crisis is more recent than we choose to remember; just as it was much closer than Garfield or anyone else in the mid-1990s realised. Several pharmaceutical companies had been quietly working on a promising new line in HIV antiviral treatment, protease inhibitors, intended to interrupt the replication process. Patient 142 had begun taking a drug called Crixivan in 1992; his viral load shrank over the next two years until it was undetectable. There were further trials. When researchers added in one or more other drugs, reverse transcriptase inhibitors such as the maligned AZT, the results were extraordinary: one early trial found that the death rate was halved. Licences were sought; the wheels of production began to turn. Combination therapy was born in 1996. They called it the Lazarus effect: patients came back to life as their immune systems reactivated; within a year or two, most hospitals had closed their Aids wards. David France went to a public meeting in New York where the news of the discoveries was announced. His partner, Doug Gould, had died in November 1992, aged 33. France was still only 35: ‘I’d lived my entire adult life in the eye of unrelenting death.’ He stumbled out of the meeting, was kissed during the celebrations by a stranger. ‘It was not over. It would never be over. But it was over.’

‘I have to admit,’ Adam Mars-Jones wrote in 1992,

that when I read an optimistic newspaper item about treatment, vaccine or cure, I feel almost threatened. Part of it is simply the sense of having been fooled before. There is also a particular pang involved, the sense that impending reprieve adds unbearably to recent casualties – to my losses, which I make stand in for the world’s. A sort of super-futility attends the death of a soldier on the day armistice is signed. Won’t the last wave of Aids deaths be the first forgotten? I imagine the Aids quilt with all its names being folded up and put away, as the victory fireworks shoot up in the sky.

Michael Callen died of Aids in December 1993, aged 38; Derek Jarman died of Aids in February 1994, aged 52; Randy Shilts died the same month, aged 42. He had refused to be told his status while he was writing And the Band Played On in case it coloured his judgment. Oscar Moore wrote his last PWA column for the Guardian in August 1996 and died in September, aged 36.

Mars-Jones was prescient in his complicated dread of the Aids crisis ending. Its place in public memory, certainly in the West, is negligible compared to its worldwide significance: HIV was responsible for at least 29 million deaths between 1970 and 2009; 37 million people were living with the virus in 2014. The total number of deaths in the US up to 2012 was 658,507 – in that year, nearly two decades after the introduction of combination therapy, nearly 14,000 Americans died of the disease. Around 20,000 Britons died, most of them gay men, but their loss appears to make little claim on us. There is no national memorial. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that, just as many of the people who got the disease were judged not worth caring about at the time, they have not been thought worthy of remembrance either.

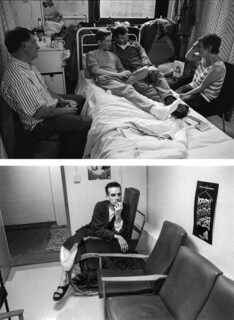

The Ward is a memorial of sorts. It’s a collection of Gideon Mendel’s photographs of four patients on the Aids wards at Middlesex Hospital in London – John, Ian, Steven and André, all of whom died – over the course of a few weeks in 1993, interspersed with short recollections by patients, relatives and staff. The pioneering wards practised holistic, patient-centred care, with few formal rules for inpatients. Nurses were encouraged to hug their charges: ‘Many patients had been deprived of human touch because of “fear of contamination”.’ Patient privacy was protected, and other people were protected from knowledge of them: ‘We made sure the ward had nothing that could identify it,’ one of the nurses remembers. ‘The plaque marking the opening of the ward by Princess Diana was covered up by a painting and HIV information leaflets and posters were kept hidden in the nurses’ rest room.’

The black and white photographs are bisected by cables, drips, tubes. There is a sense of life narrowed and squeezed into an institutional setting, but also evidence of the way life pushes resolutely back, occupying space: bottles of Ribena and Corsodyl by the bed, postcards, Styrofoam cups, clean shirts on hangers, carrier bags, takeaway wrappings, friends with their feet up, your boyfriend with his arm round your neck, Mum and Dad on either side. But then there are the needles, curtains, rubber gloves, shiny floors, masks; there is the sitting, waiting, hand-holding, wincing, staring at the ceiling, eyes-closing, and bones creeping to the surface of the skin. Turning the pages, I began to feel like I was looking at images of an old theatre production, of people playing parts on a stage-set long since dismantled and packed away. But then I was pulled up short. I knew that Oscar Moore had died at the Middlesex – many of his pieces describe his stays there – but I wasn’t expecting to find this, from Barbara von Barswisch, one of his nurses:

Do you remember Oscar Moore? … Oscar Moore used to write a column for the Weekend Guardian about living with Aids … At the time I thought he continued to do for Aids what Princess Diana had done when she visited the HIV/Aids unit at the Middlesex Hospital … When Oscar came back in the summer of 1996, he deteriorated quickly and drifted in and out of consciousness. I looked after him a lot then. I remember washing him, listening to him cursing me, the loss of control, the end. I looked at a changed man. Yet every day I tried to convey to him that even this end was OK. There were no expectations of him or of the rest of his life. His worth was unchanged by the circumstances of his debilitating illness. I was on night duty the night Oscar Moore died. He died very quietly.

Do you remember Oscar Moore?

A way of doing justice to the past is to deal justly in the present. One of the painful pleasures of reading France’s book is reaching the end and realising that some of its leading characters, marked so definitively for death, lived; Act Up’s Peter Staley and Mark Harrington look impossibly grey and prosperous these days, restored to what Nadezhda Mandelstam called the ‘privilege of ordinary heartbreaks’. Edmund White survived; so did Larry Kramer. But some of the solidarity built during the crisis years didn’t. ‘When we realised we weren’t going to die, instead we all got sick of each other,’ David Barr, another Act Up veteran, said. ‘All of us, in some way, have unprocessed grief, or guilt, or an overwhelming sense of abandonment from a community that turned its back on us and increasingly stigmatised us, all in an attempt to pretend that Aids wasn’t a problem anymore,’ Staley said in 2013. In the post-crisis years, being HIV-positive – and rates of infection went up after 1996 – came increasingly to be seen as a character flaw, understood within the moral framework imposed on the crisis by homophobes: it was indicative of recklessness, selfishness, a stubborn, stupid, dangerous refusal to imagine that actions have consequences. To become infected was – is – to let the side down, to fulfil a stereotype. Here, at last, we arrive at the shame that was my inheritance.

The discourse of personal responsibility is now structuring the discussion of pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a drug which can be taken daily to prevent HIV infection, in the same way as women take the pill to prevent pregnancy. PrEP can be prescribed on the NHS in Scotland, but not yet in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, although that hasn’t stopped bootleggers making it available. These supplies are being credited with playing a role in the extraordinary 40 per cent decline in HIV infection in London in 2017. (PrEP is widely available in the US, where its use is steadily increasing despite prohibitive costs.) The cost of a PrEP prescription to the NHS is far less than the cost of a decades-long HIV infection. And yet the condom has grown to be such a signifier of moral value that the prospect of anyone returning to casual sex without it creates fear and scandal.

Underlying all this is the sexual regime ushered in by Aids. This is Bob Geldof, speaking at the International Aids Day concert at Wembley Arena in April 1987:

It’s critical to influence people who are just beginning to grope their way into their own sexuality and to rid them of the notions that my generation imbued them with – the idea that sex is OK, the idea that you shouldn’t feel guilty, just rid yourself of all inhibitions and enjoy yourself. It’s a wonderful notion but unfortunately it’s no longer acceptable.

In France and McKay’s books, as in others, there is a note of defensiveness, almost of apology, in their discussion of the pre-Aids sexual habits of that generation of gay men: it was a culture in its infancy, we’re told, sex was merely its first preoccupation, a binding agent. All this may be true, but I wondered who was the expected audience here. I also began to feel that I wanted to know more about the sex that had led to infection, not out of prurience, but because an infection can so easily be read as an indictment; by its very nature it casts a shadow on what went before. And yet surely the sex was fun, surely part of our task in the present is to recover that fact.

Aids became entangled with gay sex, but is not inherent to it: it cannot be allowed to determine its meaning, not even retrospectively. And yet one of its effects has been to make gay sex invisible, as a condition of its respectability, its permissibility. Television and cinema still withdraw at the final moment: the recent mainstream success of the films Moonlight and Call Me by Your Name has been described as representing a breakthrough for gay narratives, but neither dared to show a single sex act. The annual Pride celebrations now come garlanded with a series of banal, cuddly messages: ‘Love is Love’; ‘Every Love Matters.’ The blandness of the rainbow flag envelops jars of Marmite and billboards for Barclays. We have been desexualised, simplified, made palatable. This represents a closing down of possibility for straights as much as for gays, a societal cringe. The challenge that queer culture has always posited is of a life without fixed points. As White put it in 1980 ‘most people’s parents are heterosexual (so much for the role-model theory of sexual orientation), and everyone is raised to be straight. Once one discovers one is gay one must choose everything, from how to walk, dress and talk to where to live, with whom and on what terms.’

For many of us it is still a life defined on a fundamental level through sex, by the fact of having sex with someone of your sex. Heterosexuality has for most of history demanded that sex put on its trousers and button up its jacket, that it be veiled by fine words and white lace, obscured by masses of children. The notion that sex can be about naked need, naked want, that sex can be without consequences, existing on the surface of things, has always been a cause for anxiety and restraint. It still needs a vanguard. ‘The aim is to open up discourse,’ Derek Jarman thought, ‘and with it broaden our horizons; that can’t be legislated for.’ We are no longer so innocent as to imagine that sex can ever be without consequences. But we know better than most, or we should, that sex leads to many things, and not only to love with a capital L. ‘As I sweat it out in the early hours, a “guilty victim” of the scourge,’ Jarman wrote in his diary in September 1989, ‘I want to bear witness how happy I am, and will be until the day I die, that I was part of the hated sexual revolution; and that I don’t regret a single step or encounter I made in that time; and if I write in future with regret, it will be a reflection of a temporary indisposition.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.