There were two anthologies of modern poetry in our house when I was a teenager and they both offered glimpses of the world outside that were more intense, more useful, than anything on television or on albums or in ordinary books. One was The Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse, edited by Kenneth Allott. It had been published first in 1950, with a second edition in 1962. The other was The New Poetry, also published in 1962. Edited by A. Alvarez, it had a crazy Jackson Pollock painting on the cover. In the Allott anthology I was intrigued by some of the poems that came towards the end, most notably Jon Silkin’s ‘Death of a Son’, whose last line (‘And out of his eyes two great tears rolled, like stones, and he died’) I thought sadder than anything in Joni Mitchell or Leonard Cohen. I was also interested in Thomas Kinsella’s ‘Another September’, because I knew the house just outside Enniscorthy where it was set and I had met the poet’s wife, whose sleeping figure was evoked in the poem. What was most interesting about it, though, was the way it left the familiar behind and moved into a set of images and cadences that I could not fully understand:

It is as though

The black breathing that billows her sleep, her name,

Drugged under judgment, waned and – bearing daggers

And balances – down the lampless darkness they came,

Moving like women: Justice, Truth, such figures.

‘Figures’ rhymes, of course, with ‘daggers’, but the rhyme is weak, almost faint, suggesting no sure-footed conclusion. Those two final words puzzled me. How would you know to end a poem with those two words?

Allott offered an introduction to each poet included in his anthology, and some of his comments read like little poems themselves. They gave me much to puzzle over. Of Kinsella’s work, he wrote: ‘The poems can be rapid, but they do not flow. Most of them give the impression of being shaped under great pressure.’ But what really made me sit up straight was his remark about Geoffrey Hill’s ‘Annunciations’, the last poem in the book: ‘I understand “Annunciations” only in the sense that cats and dogs may be said to understand human conversations (i.e. they grasp something by the tone of the speaking voice), but without help I cannot construe it.’ Alvarez’s introduction to The New Poetry, when I read it as a teenager, left me even more baffled since I had no idea who or what ‘the metropolitan pundits’ or ‘the London old-boy circuit’ he mentioned in the first paragraph were. In my Irish town, I did not know that ‘the English scene’ was ‘savage with gang warfare’. I thought that England, since the war, had reverted to being a peaceful and refined place with factories and offices where Irish people could easily find work.

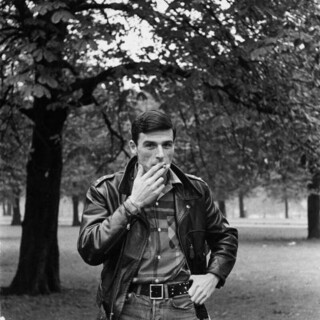

It was strange being alone with these two books; even the names of the poets – Charles Tomlinson, or David Gascoyne, or Robert Conquest, or John Holloway, or Christopher Middleton, or Geoffrey Hill – stood for a world that was fully England. Looking at the list of poets was like having one’s Irish nose pushed up against the polished glass of a posh window in some imaginary Big House. But it was clear to me that there was one poet included in both these anthologies who really meant business. His name, like his poems, had a wilful, manufactured look. (He had, in fact, changed it by deed poll from William Guinneach Gunn to Thompson William Gunn – Thompson was his mother’s maiden name.) It was clear, too, that he enjoyed his own style, his wit, his urge to dismiss what was dull and cautious, to celebrate what was dangerous and alive. This was a poetry that spoke as loudly to provincial teenagers as it did to thoughtful anthology-makers.

Gunn had two poems in the Allott anthology. The one that took no prisoners was called ‘On the Move’; its second stanza began: ‘On motorcycles, up the road, they come:/Small, black, as flies hanging in heat, the Boys.’ In the third stanza, there was a line that read: ‘Much that is natural, to the will must yield.’ (Gunn later claimed that it was only years after writing this that he learned that the word ‘will’ could mean ‘penis’, but he must have guessed. I certainly didn’t know either. It was not my job to guess.) Gunn’s sense of rhythmic certainty, his interest in power, did not please Allott, who dissented from the view expressed by both Robert Conquest and Frank Kermode that Gunn’s early poems hinted at ‘the prospect of a major poet’. Allott had two reasons: one was ‘the element of romantic immaturity that lies behind what is apparently at present Mr Gunn’s favourite poetic stance’, the other was ‘the experimental variety of poetic styles that he is still exploring’. He went on to define the ‘stance’ as ‘an emphasis on will, deliberate choice, toughness’ and wrote that he found it ‘hard to share his uncritical sympathy for nihilistic young tearaways in black leather jackets’.

Alvarez also included ‘On the Move’ among the 17 poems by Gunn in his anthology. He began with ‘Carnal Knowledge’, whose last stanza reads:

Abandon me to stammering, and go;

If you have tears, prepare to cry elsewhere –

I know of no emotion we can share,

Your intellectual protests are a bore

And even now I pose, so now go, for

I know you know.

Since I had a stammer, I paid attention to this, but even more, because I longed not to be a timid homosexual boy in a small town who had never been on a motorbike in his life or worn a leather jacket, I would have given anything to have been one of the figures in a Gunn poem, even the one from ancient Greece in ‘The Wound’: ‘The huge wound in my head began to heal/About the beginning of the seventh week./Its valleys darkened, its villages became still.’ Or the doubled figure in ‘The Secret Sharer’, who, from the street below, patiently calls his own name ‘again and again’. Or the monster in the poem of that name: ‘At once I know him, gloating over/A grief defined and realised,/And living only for its sake./It was myself I recognised’. Or the poet who could begin a poem: ‘I think of all the toughs through history/And thank heaven they lived continually.’ Or the wolf-boy ‘as yet ungolden in the dense hot night’ who ‘seeks the moon’ which ‘shall loose desires hoarded against his will/By the long urging of the afternoon’. Or the figure in ‘Black Jackets’ who ‘stretched out like a cat, and rolled/The bitterish taste of beer upon his tongue’. Or the man in ‘Modes of Pleasure’ whose triumphs ‘recurred/In different rooms without a word’, but now, older, he sits rigid, ‘brave, terrible,/The will awaits its gradual end.’

Gunn, born in 1929, studied at Cambridge before he fled England for California in 1954 to be with his partner, Mike Kitay. In Oxford, his early poems were noticed. William Wootten, in The Alvarez Generation (2015), quotes Edward Lucie-Smith: ‘We Oxford poets had an inferiority complex about our Cambridge contemporaries. The chief cause was Thom Gunn. Though his first collection, Fighting Terms, did not appear until 1954, the poems Gunn was publishing in magazines were already much discussed, and were causing ripples in a literary world well beyond our own student environment.’ Lucie-Smith’s explanation for Gunn’s success was ‘a Cambridge passion for Eng. Lit… . combined with a rather taking bully-boy strut’. Philip Hobsbaum, also alert to Gunn, took the view that the poem ‘Carnal Knowledge’ was ‘slick’ and ‘execrable’. Alvarez, as Wootten notes, reviewed Gunn’s first book twice. In one review, he called the collection ‘for my money, the most impressive first book of poems since Robert Lowell’s’. He went on: ‘There is … a great vitality in his poems that makes Gunn sound, in a wholly contemporary way, rather like Donne … the Donne who, out of impatience with the pieties of Elizabethan verse, changed the language of poetry to suit his own colloquial intelligence.’

Wootten, like many other readers of Gunn, is uneasy about what was lost in Gunn’s subsequent collections. In a wonderful sentence, he writes of the leather-clad motorcyclists in ‘On the Move’: ‘This is more of a mask than it is a simple escape from personality, and, as a model for poetry, much closer to a fetishistic self-fashioning than it is to ascetic self-abnegation.’ He writes that a number of poems in Gunn’s second volume, The Sense of Movement (1957),

are no longer poems of the wounded or divided self but of the self-created and asserted. The change makes Gunn more coherent, a poet who knows what he’s about, yet the cost paid is the loss of the great sense of strangeness, splitting, wounding, of the irresolvable interior and exterior drama that is to be found in Fighting Terms.

Gunn’s first Selected, a volume shared with Ted Hughes, came out in 1962, when he had published only three books of poetry. It was to sell more than eighty thousand copies. The original idea was also to include Philip Larkin, a poet both Gunn and Hughes admired – in a letter to his sister Hughes called him ‘a very good gentle poet’. Larkin did not share the admiration. He wrote to Conquest about this idea for a Selected Poems of ‘Thom, Thed and Yours Thruly’: ‘Honestly, I’m sure they’re good chaps, and there’s nothing personal about this, but I can’t think of any two who affect me less.’

Allott had written about ‘the experimental variety of poetic styles’ that Gunn was still exploring. In this early selection of 19 poems, Gunn’s addiction to the pure iambic beat is apparent, as is his interest in working with both strict stanza form and clear rhyming schemes. There is also a sense of distance – at times of artifice – in the voice. It may be a speaking voice, but it comes into sound at one remove, more alert to its place in a poetic tradition than fully involved in the world. Apparent, too, in a poem such as ‘In Praise of Cities’, is a problem that Gunn was always going to face. When he relaxes his beat, and becomes more casual, the tone slackens and can move towards the weak, the banal:

You stay. Yet she is occupied, apart.

Out of a mist the river turns to see

Whether you follow still. You stay. At evening

Your blood gains pace even as her blood does.

Gunn is also capable of being portentous, something he perhaps shares with Hughes. The last two lines of ‘In Santa Maria del Popolo’ – ‘For the large gesture of solitary man/Resisting, by embracing, nothingness’ – help us realise that Gunn has been reading Sartre, but do not help us to see St Paul in a painting by Caravaggio, which is what they are meant to do.

But in two of the later poems in this early selection – ‘Considering the Snail’ and ‘My Sad Captains’ – when Gunn uses a seven-syllable unstressed line, the conflict between structure and lack of structure allows him a chiselled simplicity, a naturalness of tone and a sense of textured ease that enrich the voice while keeping it within touching distance of ordinary speech. (‘There’s something going on there with the sounds that I’m amazed I was able to achieve,’ Gunn said.) ‘Considering the Snail’ – inspired, Clive Wilmer tells us, by Paul Klee’s painting from 1924 – begins:

The snail pushes through a green

night, for the grass is heavy

with water and meets over

the bright path he makes, where rain

has darkened the earth’s dark. He

moves in a wood of desire.

Wilmer, in his introduction to the new Selected Poems, writes that Gunn always insisted that his use of syllabics ‘was a stage on the road to free verse, which he had earlier found difficult to write’. He notes that ‘Touch’, written in 1966, after the syllabic poems, ‘reveals a new Gunn able to write without the overt constraints of either iambic metre or syllabics’.

Gunn, as he tightened and relaxed his metre, as he obeyed the rules and played with form, opened himself up to influences that included figures who could not have been more different from one another: the formidable Yvor Winters, with whom he studied in Stanford (‘You keep both Rule and Energy in view,’ Gunn wrote of him), and Robert Duncan, who was interested in a much looser, open style, as well as other Americans such as William Carlos Williams. Wavering between systems, Gunn didn’t please everyone. In August Kleinzahler’s introduction to the third Selected, which appeared in 2007 (the second came in 1979), Kleinzahler quoted two anthologists on the decline of Gunn. The first was Lucie-Smith:

Around 1960, it sometimes seemed as if all the poetry being written in England was being produced by a triple-headed creature called the ‘Larkin-Hughes-Gunn’. Of this triumvirate it is Gunn whose reputation has worn least well. The youngest of the Movement poets, he established himself with his first volume. A mixture of the literary and the violent, this appealed both to restless youth and academic middle-age … Afterwards Gunn went to America.

The other was from The Penguin Companion to the Arts in the 20th Century (1986), in which Kenneth McLeish wrote:

On the present showing, Gunn is living proof of that sad cliché that first thoughts are always the best … His collection Fighting Terms was one of the best poetry books of its time: a combination of urgent style and that sparky, intellectual involvement with ‘issues’ … [but] only My Sad Captains (1961) contains anything to match … or remotely rival his own spectacular early work.

The accepted view of Gunn, as Kleinzahler sums it up, was that in 1954 he ‘had removed himself to California where he would, as was alleged over and over, begin his long decline, undone by sunshine, LSD, queer sex and free verse’. Kleinzahler sought to challenge this idea of the softening of Gunn’s brain in California. ‘The city,’ he wrote, ‘will become his central theme, character and event being played out on its street corners, in its rooms, bars, bathhouses, stairwells, taxis.’ Kleinzahler also notes that, even when the poems became more relaxed and contemporary, ‘the “I” of the poetry’ carried ‘almost no tangible personality. This can be upsetting or disappointing to the contemporary reader, especially the American reader, accustomed to the dramatic personalities behind the voices in recent poetry: Lowell, Berryman, Sexton, Ginsberg, Plath, Hughes, et al. Even in Larkin there exists a strong, identifiable persona, no matter how recessive the tone.’

In Gunn, this was deliberate. In an interview he said:

People do have difficulty with my poetry, difficulties in locating the central voice or central personality. But I’m not aiming for central voice and I’m not aiming for central personality. I want to be an Elizabethan poet. I want to write with the same anonymity you get in the Elizabethans and I want to move around between forms in the same way someone like Ben Jonson did. At the same time I want to write in my own century.

Kleinzahler singles out two poems from Gunn’s 1971 collection, Moly, which Gunn viewed as ‘unquestionably my best book’. The opening poem of that volume, ‘Rites of Passage’, is for Kleinzahler ‘one of the thrilling moments in 20th-century poetry’. It begins:

Something is taking place.

Horns bud bright in my hair.

My feet are turning hoof.

And, Father, see my face

– Skin that was damp and fair

Is barklike and, feel, rough.

The other poem, ‘At the Centre’, was written while on an LSD trip. It is a perfect example of Gunn as somehow far away, speaking with urgency, but uneasy with the notion of identity. He is in the poem, feeling and seeing, but also away from it, sensing and questioning:

What place is this

And what is it that broods

Barely beyond its own creation’s course,

And not abstracted from it, not the Word,

But overlapping like the wet low clouds

The rivering images – their unstopped source,

Its roar unheard from always being heard.

Kleinzahler includes 26 poems in his selection of 59 that are not included among the 71 chosen by Wilmer in his new Selected Poems. He includes only two from Fighting Terms compared to Wilmer’s five; and four from The Sense of Movement, compared to Wilmer’s nine; and 13 poems from Moly, compared to Wilmer’s nine. He also includes ‘Well Dennis O’Grady’, from The Man with Night Sweats. It is a short, casual, city poem, in the American grain, like something overheard, quickly noted down, not revised, fresh from the street. The first stanza reads:

Well Dennis O’Grady

said the smiling old woman

pausing at the bus stop I hear

they are still praying for you

I read it in the Bulletin.

It does not improve in the second stanza. Kleinzahler also includes six of Gunn’s laments for friends who died of Aids; Wilmer includes five. Both choose ‘The Man with Night Sweats’, ‘Lament’, ‘The J Car’ and ‘The Missing’, four of Gunn’s greatest poems, which combine a tone almost casual, close to speech, but with rhyme schemes that could belong in a ballad. The ease with strict metre, the early sureness, is mostly absent here, often replaced by a deliberate awkwardness, a hesitancy. The voice remains hushed and impersonal, but it is desperate to be heard.

In these poems, Gunn is watching something that has always inspired his poems, the body during a time of change, the thin line between waking and sleeping, between life and death, between the human and some other form, but now the subject is real, close, exact; the poems centre on loss and pain, on what sickness looks like. These poems may seem to be departures, but they contain many echoes and traces of Gunn’s earlier work. He had always taken risks with rhyme: ‘guess/bitterness’; ‘chance/experience’; ‘character/confer’; ‘heritage/rage’; ‘went/obedient/experiment’. And with couplets: ‘People are wading up the stream all day,/People are swimming, people are at play’; ‘An air moves over us, as calm and cool/As the green water of a swimming pool’; ‘You cannot guess the weed I hold,/Clara Green, Acapulco Gold.’ (In a letter to Tony Tanner from May 1968, he wrote: ‘I have a lot of the best ever grass – it is known as Acapulco Gold and is $15 a lid, it is that good.’) He was always interested in the body and the bodiless, or of the body transforming, being taken over by another force. In ‘The Value of Gold’:

Of insect size, I walk below

The red, green, greenish-black, and black

And speculate. Can this quiet growth

Comprise at once the still-to-grow

And a full form without a lack?

And, if so, can I too be both?

Gunn loves ‘the luminous half-sleep where the will was lost’, the time between sleep and waking. He often writes a poetry of drowsing, dreaming, with liminal musings, perception sharpening and then waning. The body for him is open to suggestion, ready to turn easily, almost naturally, into some other form. Being human in some of the poems is a waiting game, flesh fully fragile. ‘The Inside-Outside Game’ will end:

I saw the world’s nerves, then I turned about

To see myself, uncreased and inside out.

Look, look: rose tracing and bone imprint bare,

Raw to the air’s blade. And I touched the air.

In poems such as ‘The Allegory of the Wolf Boy’, ‘For Signs’, ‘The Messenger’ and ‘Rites of Passage’, the human is ready to transform, feel ‘the familiar itch of close dark hair’ or live closer to the moon than the earth. In these poems from Moly, Jack Straw’s Castle (1976) and The Passages of Joy (1982), Gunn has ceased to be a poet of swagger, exalting the will and violence; he has been gentled into precarious states of consciousness, letting in mystery, the numinous, the shadowy, blurring the lines between what is seen, what is imagined and what is barely dreamed of.

He relishes northern California with its hot sun, its beaches and blue skies – his poem ‘Sunlight’, he wrote, was his ‘favourite poem by myself’ – and he loves the present moment, the bodies he encounters or observes, and the sex he has, the hedonism, the sensuality. But he is always alert to questions about beauty and goodness and time: ‘If you put your trust in the temporal and the finite, you are putting your trust in what will inevitably fail you,’ he wrote. Wilmer quotes from a notebook in the Gunn archive at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley:

the (sudden) unavoidable realisation of how self-destructive I am … when I have always – always – assumed I was the opposite. Maybe needs thinking out in terms of dreams, also in relation to my confusion of values.

How do I work out the relation of my in general hippie values, I mean I do believe in love & trust etc, and then the other thing? I say that s & m is a form of love. I think it is, but I don’t think that goes quite deep enough.

Gunn is fascinated by the idea of unknowing, the moment when clarity becomes open to a space beyond clarity, whether drug-induced or part of a dream, or a time when the mind is half-awake and thus ready to ‘forge and raise impossibility’, as one of Gunn’s favourite 16th-century poets, Fulke Greville, wrote. It is this deep interest in the line between consciousness and its fading, between knowing and fantasy, that gives ‘Touch’ its intensity, making it his most successful venture in free verse, and this too nourishes the mysterious but fully shaped landscape of section ten of ‘Misanthropos’. (‘I adore this poem, and don’t know how I wrote it,’ he told Tanner.)

Gunn began his introduction to a 1974 selection of Ben Jonson’s poems with the sentence: ‘There are many Ben Jonsons to be found in this selection, and each of them is a considerable poet.’ The same could be said of Gunn himself, who came in many guises: the young poet of great technical command, in love with defiance and energy; then the poet of dreams and transformations; then the great elegist; then the poet inspired by street life in San Francisco and the fun you could have with drugs and sex and cheap thrills. In his Jonson introduction, Gunn takes issue with the idea that the phrase ‘occasional poetry’ might ‘indicate trivial or insincere writing’:

Yet in fact all poetry is occasional: whether the occasion is an external event like a birthday or a declaration of war, whether it is an occasion of the imagination, or whether it is in some sort of combination of the two. (After all, the external may lead to the internal occasions.) The occasion in all cases – literal or imaginary – is the starting point, only, of a poem, but it should be a starting point to which the poet must in some sense stay true.

In many poems, it’s a glimpse or glance or gaze that gives him his chance. In ‘The Rooftop’, he is content ‘to sit here for hours,/Becoming what I see’. In ‘Grasses’, written in ‘the dust of summer’, ‘we sit/High on a fort, above grey blocks and wells,/And watch the restless grasses lapping it.’ In other poems, he inhabits the foggy light of San Francisco: ‘The month is cool, as if on guard,/High fog holds back the sky for days’, or observes the city’s mean streets ‘where worldly Market Street/meets the slum of Sixth’. Or wallows in the city’s casual pleasures: ‘We greet/Two other guests on Market Street/And hit the Balcony for a drink’. In these poems, Gunn finds a tone to match his sense of ease. ‘The Night Piece’ is a perfect eight-line lyric about walking home in fog. Its second stanza reads:

Here are the last few streets to climb,

Galleries, run through veins of time,

Almost familiar, where I creep

Toward sleep like fog, through fog like sleep.

In his watching, however, there are often shadows. One of them is the process of ageing, dramatised for example in the first of the ‘Modes of Pleasure’ poems; another is death. In ‘A Waking Dream’, he calls out the name of a dead friend:

And the head turns: it is indeed his,

but he looks through me and beyond me,

he cannot see who spoke,

he is working out a different fate.

In ‘The Corporal’, the last word of every stanza is death:

One I remember best, a corporal

I’d notice clumping to and fro

Piratical along my street,

When I was about fifteen or so

And my passion and concern was death.

In ‘Talbot Road’, written in memory of his friend Tony White, section five begins:

That was fifteen years ago.

Tony is dead, the block where I lived

has been torn down.

Thus, when the great poems in The Man with Night Sweats appeared in 1992, their themes had been long rehearsed. ‘The Hug’ is one of his waking/sleeping poems: it’s about the body, about love and about ageing, about feeling ‘the stay of your secure firm dry embrace’. (‘The Hug’ was, Wilmer notes, the result of a challenge to himself: ‘OK, Gunny, try to write 10 rimed poems in 10 weeks.’) Since Gunn was one of the great poets of the body, seeing the impulse for pleasure as a sort of moral imperative, his poems about his friends taken by Aids place eloquence and command beside pain and shock. The 17 poems in section four of The Man with Night Sweats, all dealing with death and dying, have echoes in many earlier poems, but come now with a fierce sense of completion – as though his earlier poems about death had merely been ways of gathering strength. In October 1987, he wrote to a friend: ‘I have had other friends die at other times, but the worst was from August 8 to September 9, during which time I lost four friends – friends and acquaintances – two of them on the same day. After the first three I thought I was holding up surprisingly well, but the fourth one – poor Charlie who was only thirty, and so full of promise – really did me in.’

His reading of Thomas Wyatt and Ben Jonson, and the attention he paid to the elegies they wrote, were preparations too. As Wilmer writes, he admired the ‘valuation of friendship’ in Jonson’s poems about death, ‘their unadorned manner’ and ‘the deep poignancy of their stoical reticence’. Alan Jenkins has pointed out that Gunn’s elegies ‘show all the discipline of the early verse, and for all their calm and unflinching truthfulness about the effects of the disease, carry a charge of personal emotion that is unprecedented in his work’. ‘Lament’ opens:

Your dying was a difficult enterprise.

First, petty things took up your energies,

The small but clustering duties of the sick,

Irritant as the cough’s dry rhetoric.

Those hours of waiting for pills, shot, X-ray

Or test (while you read novels two a day)

Already with a kind of clumsy stealth

Distanced you from the habits of your health.

There are some poems I miss in Wilmer’s selection, most notably ‘The Night Piece’, ‘The Reassurance’ and ‘Memory Unsettled’, but at least they can be found elsewhere (some in Kleinzahler’s volume). What is remarkable about his book are the often detailed notes on each poem, using letters and diaries and notebooks from Gunn’s archive that Wilmer, who first read his work in Alvarez’s anthology and was a friend for forty years, has carefully gone through. In his note on ‘Carnal Knowledge’, Wilmer quotes a letter to Karl Miller, written in July 1952, in which Gunn describes his efforts at heterosexual sex and writes that two heterosexual male friends

are at present trying to persuade me to make love to a dear little girl from Leeds whom they assure me has indicated I would not be disagreeable – you would think her very lovely, and she is – but I have learned by the affair with Ann that one must not enter on such things if one cannot be happy in them and make the girl happy.

Wilmer includes a not very good poem called ‘Expression’, which Gunn might have been wiser not to have published at all. But it remains interesting because it throws light on his reticence and impersonal tone. It opens:

For several weeks I have been reading

the poetry of my juniors.

Mother doesn’t understand,

and they hate Daddy, the noted alcoholic.

They write with black irony

of breakdown, mental institution,

and suicide attempt, of which the experience

does not always seem first-hand.

It is very poetic poetry.

In his introduction, Wilmer writes that in 1965 he lent Gunn copies of Sylvia Plath’s last poems. When he returned them, Gunn wrote that they ‘make a kind of rambling hysterical monologue, which is fine for people who believe in art as Organic but less satisfactory for those who demand more’. He admired ‘some incredibly beautiful passages’, but felt that ‘the trouble is with the emotion, itself, really: it is largely one of hysteria, and it is amazing that her hysteria has produced poetry as good as this. I think there’s a tremendous danger in the fact that we know she committed suicide. If they were anonymous poems I wonder how we’d take them.’ In The Alvarez Generation, Wootten quotes the opening two lines of Gunn’s late poem ‘My Mother’s Pride’: ‘She dramatised herself/Without thought of the dangers.’ Gunn’s mother committed suicide in December 1944, when Gunn was 15, by gassing herself, leaving her two sons to find her. Like Plath, she was the mother of two children. As Wootten writes, ‘the connection between one mother who dramatised herself without thought of the dangers, who gassed herself leaving two children behind, and another is not a difficult one to make.’

‘Rites of Passage’ ends:

I stamp upon the earth

A message to my mother.

And then I lower my horns.

‘Death’s Door’, published more than twenty years later, opens:

Of course the dead outnumber us

– How their recruiting armies grow!

My mother archaic now as Minos,

She who died forty years ago.

‘It is beginning to be clear,’ Wilmer writes, ‘that Gunn’s last two books were carefully planned as the formal conclusion to his life’s work.’ Gunn’s last book, Boss Cupid (2000), includes ‘The Gas-poker’, his only poem directly about the death of his mother. In his note on it, Wilmer points out that it was ‘composed … unusually quickly by G’s standards’. He quotes from the diary entry Gunn wrote at the time of his mother’s death:

She committed suicide by holding a gas-poker to her head, and covering it all with a tartan rug we had. She was lying on the sheepskin rug, dressed in her beautiful long red dressing-gown, and pillows were under her head. Her legs were apart, one shoe half off, and her legs were white and hard and cold, and the hairs seemed out of place growing on them.

Later in this long diary entry, Gunn wrote:

But oh! mother, from the time when I left you at 11 on Thursday night until four in the morning, what did you do? She died quickly and peacefully, they said, but what agonies of mind she must have passed through during the night. I hate to think of her sadness. My poor, poor mother; I hope you slept most of the time, but however sad then, you are happy now. Never will you be sad again! Dear, dear, sweet mother.

All his life Gunn sought to avoid this tone in his poetry. As Jenkins writes,

a part or a pose, an impersonation, a posture or imposture: all are ways of avoiding the direct expression of feeling. The will, in these poems, is expected to master the emotions: that is the point of it … Form, rather than a discipline for emotion, becomes a way of refusing entry to it; rigid stanzaic and metrical patterns become, like the soldier’s uniform, self-protection, shield and disguise, or like the biker’s leather jacket, ‘donned impersonality’.

In an extended interview with James Campbell, published in 2000, Gunn said of his mother’s death:

I wasn’t able to write about it until just a few years ago. Finally I found the way to do it was really obvious: to withdraw the first person, and to write about it in the third person. Then it came easy, because it was no longer about myself. I don’t like dramatising myself. I don’t want to be Sylvia Plath. The last person I want to be! I was trying in this poem to objectify the situation … I think I probably got a bit of help from Thomas Hardy writing that poem, the emphasis on the rather awkward forced rhymes: barricaded/they did, and so on.

‘The Gas-poker’ is a lightly metred, lightly rhymed poem, with five stanzas of seven lines. It begins:

Forty-eight years ago

– Can it be forty-eight

Since then? – they forced the door

The ‘they’ of course is ‘we’, since it was Gunn and his younger brother who forced the door. Stanza three begins: ‘The children went to and fro/On the harsh winter lawn.’ The children were the poet and his brother. It is, however, as though he was not fully there, merely watching from a distance, or inhabiting only part of himself, and it is as though he is not there now either, merely imagining, keeping what happened carefully at bay. The third stanza ends with ‘Till they knew what it meant’, and the fourth stanza opens: ‘Knew all there was to know’. No further knowledge can be gained. Perhaps that stark, melancholy thought is what is being registered in the poem. The children ‘take the appropriate measures’, as does the poem itself, 48 years later, through its tone and diction. In the final stanza Gunn gives up on plain, unadorned fact and – in a way that is both distancing and consoling – makes use of allegory and suggestion. He moves away from the idea that this happened to someone else by not using ‘his stubborn mind’ but rather ‘the stubborn mind’. He would never write ‘my stubborn mind’; as he makes his rhymes more pure, he keeps himself away. He has always known how to do this.

In evoking the idea of music – the gas-poker as an instrument in his mother’s own lament – Gunn offers himself, and us too, some consolation, if not too much. ‘The image of the flute,’ Wilmer writes, ‘owes something to classical tradition: when Pan chases Syrinx she escapes him by turning into a reed. Instead of taking her virginity, he plucks the reed, makes a flute of it, and plays a lament on it.’ The poem’s final stanza reads:

One image from the flow

Sticks in the stubborn mind:

A sort of backwards flute.

The poker that she held up

Breathed from the holes aligned

Into her mouth till, filled up

By its music, she was mute.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.