Eight million horses perished in the First World War, along with untold numbers of donkeys and mules, just as the ascendency of the car made clear that the pervasiveness of the horse as a working animal was coming to an end. The disappearance of the horse from urban –and later rural – life didn’t happen overnight. Horses and donkeys were still found in great numbers in British towns and cities until just after the Second World War, when the shift to motorised transportation of goods caused the collapse of the equine market and 200,000 city animals were euthanised in a two-year period. The farm population dropped steeply, from nearly 1.1 million in 1944 to 147,000 a decade later. What Isaac Babel called obyezloshadenie, or dehorsification, unfolded over a longer period, and more recently, than we might think.

Horses were as ubiquitous in the 19th century as cigarettes were in the 20th and some saw them as no less a threat to public health. In England in the 1860s there were as many horses in cities as in the countryside, and by the turn of the century urban horses outnumbered country horses two to one. Equine density was even greater in the United States. In New York there were nearly five hundred horses per square mile, an astonishing figure that works out to around one horse for every four New Yorkers. In the years between 1860 and 1900, the historian of science Ann Norton Greene has noted, a banker in Boston would have seen more horses than a Colorado cowboy or a Texas rancher. Cities were crowded and smelled awful: horses left about 1100 tons of manure on the streets of New York every day, along with 71,000 gallons of urine. In place of honking taxis and beeping car alarms, imagine the rattle of stagecoaches and clinking horseshoes on cobbled streets, punctuated by the staccato of drivers’ whips. The thwack of a whip, Schopenhauer said, ‘slices through one’s brains and shatters one’s thoughts’. Horses also required stables, water troughs and, in due course, knackers’ yards (the lifespan of city horses varied but five years was the norm before their knees started to go).

‘There was an entire geography,’ Susanna Forrest writes in The Age of the Horse,

from mews, coach houses, jobmasters’ stables, fodder merchants, knackers, harness makers, smiths, wheelwrights, whip makers, loriners, rat catchers, tanners, makers of straw sun hats for horses, strappers who specialised in vigorous grooming, ostlers at inns, riding masters, horsebreakers and common or garden grooms. In the same way that the horse left its mark on the titles of the aristocracy of Europe, the Ritters, Cabelleros and Chevaliers, so it marked the surnames of the ordinary man: the Smiths, Grooms, Carters, Wheelers, Wainwrights, Cartwrights, Jaggers, Packers and Sadlers.

The rise of the steam engine actually increased the dependence on equine power. In the US, the number of horses and mules grew sixfold, to nearly 27.5 million, between 1840 and 1910, a rate almost twice that of its human population. Comparable increases were seen throughout Europe. Often working in tandem with steam technologies, horses were used to harvest, thresh and bale hay, and in mills to grind flour; to pull stagecoaches and canal boats over long distances and omnibuses, streetcars and hackney cabs over shorter ones; to move goods to and from factories, farms and markets around the clock. A world without horses must have been as hard to picture as it is for us to imagine a world without cars and trucks. Forrest describes a steam tram that had an engine disguised as a horse’s head, neck and chest, a bell stuck between its ears, and a booth for the driver where the animal’s body would have been. The design was arrived at so as ‘not to frighten the horses’, which the tram’s inventor could not imagine disappearing from city streets any time soon.

In hindsight, there is something odd about an industrial revolution built on the back of a four-legged animal. The horse is rife with contradictory meanings: at once friendly and fierce, domesticised and bred for warfare, anachronistic aristocrat and disposable prole. It could be the symbol of appalling animal maltreatment – an image mythologised in Nietzsche’s breakdown in Turin in 1889, after he witnessed the flogging of a workhorse – and the source of a growing compassion for animals. Activists in the US distributed copies of Anna Sewell’s novel Black Beauty (1877); the founding emblem of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was an angel intervening as a teamster beats a carriage horse. Forrest describes the affection felt by workers for their animals:

‘He never came home from work until [his horse] Tabby was comfortable for the night,’ recalled the niece of one carter at the Coventry Station goods depot. Another man there would ‘bike out into the country, go down in the hedgerow, pull out my knife … And I’d cut a big, juicy faggot of dandelions. I’d stand by the stable door and shout “CHARLIE! Charlie! Come on, boy!” Up would go his old head, his ears pricked. He knew my voice like a child knows its father’s.’

‘Most of us loved our ponies and treated them as pets,’ one miner said. ‘A pit pony would get you back to the stables in the dark. You just held on to its tail or mane and kept walking.’

In Farewell to the Horse, the literary critic Ulrich Raulff is alert to the absurdities, paradoxes, curiosities and comic possibilities associated with the human reliance on the horse. Take the ‘pastoral incident’ in Laurence Sterne’s Sentimental Journey, where a dead donkey in the road causes the bidet ridden by La Fleur to upset its load and run away, forcing La Fleur to ride in the chaise with the narrator, Yorick. (The bidet, a small French posthorse ridden low to the ground, also gave its name to the item of plumbing.) Raulff sees this story and De Quincey’s tale of near death at high speed in ‘The English Mail-Coach’ as prescient narratives in which the horse is both harbinger of and impediment to the modernisation of the countryside. Raulff’s cultural history is full of live horses and dead asses, in the road, in the mills and mines, and on the battlefield. He describes the way artists, novelists, military thinkers, biotechnicians, connoisseurs and entrepreneurs came to interpret and internalise the strange ‘Centaurian Pact’ they had made with the creature:

The great novels of the last century of the horse – the ones set on terra firma rather than on the high seas at any rate – have horses in their very fabric … This is true even for the most cosmopolitan writers of the time: one thinks of Stendhal, Balzac, Flaubert, Tolstoy and Robert Louis Stevenson. Every single great idea that fuelled the driving force of the 19th century – freedom, human greatness, compassion, but also the subcurrents of history uncovered by contemporaries, such as the libido, the unconscious and the uncanny – can be traced one way or another back to the horse. Of course, the horse is no sphinx. But the animal was certainly the bearer of many of the great ideas and imagery of the 19th century; it was its intellectual assistant, its speech therapist.

Raulff, who has written books on Marc Bloch, Aby Warburg and Stefan George, makes inspired connections across the history of technology, critical theory, military history, cultural anthropology, philosophy and art. Farewell to the Horse is a narrative that combines odd historical back alleys and literary anecdotes with Spenglerian pronouncements about a world gradually uncoupling from nature, agriculture and the horse. But whatever one makes of its epochal self-consciousness, this is a vastly imaginative way of writing cultural history. Raulff is capable of drawing a line from, say, the Warburgian theorising of the retired cavalry officer Richard Lefebvre des Noëttes to the biopolitics of the Middle Ages; or tracing the mounted political figure from Kant’s grumbling about the new King of Prussia arriving in Königsberg in a carriage to the caparisoned horse of President Kennedy’s funeral cortège. Figures from Paul Mellon to Siegfried Kracauer, Robespierre to Claude Simon, whose cavalry unit was massacred in World War Two, put in appearances, as do Clever Hans, Comanche (the purported lone survivor of Custer’s Last Stand) and Anna Karenina’s ill-fated Frou-Frou.

Raulff is especially interested in the iconography of the horse, and his text is peppered with photographs showing military animals in splendid formation, mass equine graves and summary executions, authors riding horses, and authors like Lord Berners painting horses (the horse is standing obediently inside his Oxfordshire manor). He discusses Stubbs’s 1762 portrait of the racehorse Whistlejacket, with its proto-modern background of empty brownish-grey (save for the cast shadows). This painting, which baffled contemporaries (they thought a picture of that scale ought to show the king in the saddle), freed the animal from its pastoral limitations. In the age of Degas and Muybridge, the canvas and the light-sensitive plate brought about a new idea of the horse, informed by veterinary science, technological progress, aesthetic modernism and political ideology.

‘Anthropologists see the man, historians see the farmer, technologists see the plough,’ Raulff writes, ‘whereas nobody sees the horse.’ For 25 centuries, beginning with Simon of Athens and Xenophon’s On Horsemanship, people have written about the art of riding and caring for horses, but our knowledge of horse behaviour is surprisingly scanty. The 1970 survey Ethology: The Biology of Behaviour contained an extensive bibliography, with 1351 entries. Only three of these were concerned with horses, and none detailed the conditions of life in the wild. As one equine researcher noted, even in 1980 far more was known about the social life of zebras than about free-ranging horses. The early historical record continues to be overturned. The discovery of piles of bones, pottery and settlement remains in northern Kazakhstan a decade ago moved the date of the domestication of horses back by a millennium, to around 3500 bc. More recent paleogenetic research has cast doubt on the theory that the Botai horses of Kazakhstan were even the first to be domesticated.

A remarkably adaptable creature, the horse is able to survive in the wild in vastly different climates: the prairies of the Argentine pampas; the Kaimanawa mountains of New Zealand; the lush coastal hills of Cape Toi, home to one of eight breeds native to Japan. Descendants of the Spanish horses introduced by the conquistadors are found in Wyoming, Nevada and Arizona; feral horses inhabit Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia, and Assateague Island on the Virginia/Maryland state line (famous to generations of American children weaned on Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague), as well as the bone-dry Namibian desert.

All these are feral horses rather than wild ones. It may be that no wild horses remain. Przewalski’s horse, named after a Russian explorer, was thought to be the last truly wild breed, though now it seems likely that they are descended from the domesticated Botai. Stocky and short-legged, they resemble the creatures on the cave walls at Lascaux rather than anything at Newmarket. They are distinct in other ways as well, having 66 chromosomes rather than the 64 of the domesticated Equus caballus. Only around two thousand survive, in zoos and reserves, including the land around Chernobyl. Forrest recounts a trip to see one of the largest herds of Przewalskis, in a national park about sixty miles from Ulaanbaatar where they are part of an attempt to re-establish the breed in Mongolia. ‘Humans have a lamentable habit of loving late,’ Forrest writes, ‘and so it was with the wild horse.’ She begins her story with the attempts of early zoological hunters to capture the vanishing ‘wild’ horses of Eastern Europe and Asia: Przewalskis, or takhis; and tarpans, from the Russian steppe, which died out in the late 1800s. Przewalskis survived because their homeland remained remote and uncultivated. In 1901, the German circus and zoo owner Carl Hagenbeck dispatched an agent to Kobdo in Mongolia to capture the elusive horse. He trekked over snow and ice, spending four months camped in the wilderness. Most of the 52 foals he caught died on the long journey back to Hamburg, but the ones that survived were dispatched to zoos around the world and became a source of fascination in Germany in particular. There, völkisch notions of nature and Wagnerian fantasies of the Teutonic wild inspired a programme to create a super-race of horses through selective breeding of the descendants of Polish field horses and the now extinct tarpans.

There were literary fantasies too. Byron’s poem ‘Mazeppa’ (1819) tells the story of a Ukrainian nobleman who cuckolded another count. When the affair is discovered, his punishment is to be strapped naked to the back of a savage steed, which gallops madly until it reachs its ‘Tartar’ homeland, a ‘veritable kingdom of wild horses’. When the horse collapses and dies, Mazeppa’s life is saved by a ‘Cossack maid’ with eyes as black as the stallion’s. Byron’s Orientalist fantasy inspired paintings by Géricault and Delacroix, poems by Pushkin and Hugo, an étude and a symphonic poem by Liszt, and an opera by Tchaikovsky; it also lent its name to yachts, steamboats, pubs, locomotives and, less surprisingly, racehorses. Mazeppa became one of the most successful of the hippodramas that took London, Paris and New York by storm in the 1820s. Part circus, part successor to the elaborate manège routines carried out by elite groups of royal horses, these equine spectacles combined melodramatic stagecraft and inspired horsemanship. After one production opened in Paris in 1825, Forrest writes, it was quickly followed by a version at Astley’s Amphitheatre in London. The showman Andrew Ducrow expanded Byron’s text to take advantage of the latest theatrical machinery and special effects:

The actor John Cartlich was tied to the back of the ‘wild horse’ and exited the stage to be replaced by another horse with a dummy … This horse and dummy then careered up the helter-skelter mountain course, crisscrossing the stage left to right and back again, all the way to the flies, with off stage thunder, lightning and rattling ‘hail’.

The show ran for 1500 performances and inspired numerous copies and spin-offs.

Few subjects or scenes were too ambitious or too camp to be treated as topics for a hippodrama. Audiences could see ‘Rocinante and Dapple flying to heaven on a cloud, blue-eyed cremello ghost horses carrying the spectres of defeated Indians, castles that go up in flames, Lady Godiva, horned horses, the five-year-old “Elfin Equestrian”, Epsom on Derby day, six fairy ponies, one of whom leapt over the others, and two hundred Arabian horses re-enacting the Fall of Khartoum’. The equine performers were such celebrities, according to Forrest, that when one was injured special bills were printed and distributed to reassure the public of its return.

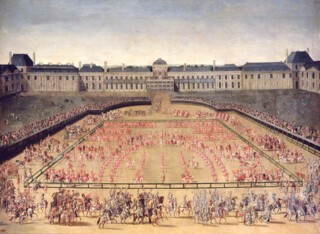

Hippodramas are the black sheep in the family history of dressage. The training and precision demanded bore a close resemblance to the horsemanship at royal stables like those at Versailles, which at its height under Louis XV housed 1700 horses under the care of 2000 men. These in turn linked the Ancien Régime and the hippika gymnasia, the exercises carried out by elite corps of Roman horse soldiers, and the furusiyyas, the mounted martial games of Arab horsemen in the golden age of Islam. Chivalric horsemanship became a highly aestheticised code of royal might. Antoine de Pluvinel, who in 1594 founded the academy that would become known as the School of Versailles, wrote that to ride well was to ‘attain perfection’ and required a combination of ‘patience, resolution, gentleness and force’. It also required the breeding and training of a horse that was nimble, intelligent and powerfully athletic. After riding a pirouetting Andalusian horse, William Cavendish, the Duke of Newcastle, reported that ‘I was so dizzy that I could hardly sit in the saddle.’

Pluvenal’s greatest refinement was the extravaganza of pomp that became known as the carrousel, a word today associated with the fairground ride. The original carrousel was a jousting exercise in which knights galloped in a ring while throwing balls to one another; during the 17th century it became a highly choreographed royal spectacle. A version emerged as a game played by commoners at fairs: riders would try to spear hoops hanging overhead as their horses cantered round in a circle. The place du Carrousel, in the courtyard of the Louvre, was home to one of the first wooden carousels before it became a popular spot for revolutionary executions; the riding school run by Louis XV’s master of dressage, François Robichon de la Guérinière, was transformed into the National Assembly in 1789. Not many years before the erection of the guillotine, James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine, had adopted the word ‘horsepower’. It would be more than a century before horseless carriages gained the upper hand and ‘motor stables’ began to displace horse stalls for good. The British railway system in 1948 still had nearly nine thousand horses, assisting in shunting vehicles and short-distance transport. In 1967 the last of them, a Clydesdale called Charlie, was put out to pasture. Nor are there many horses to be seen in New York, though the Bronx Zoo still has a small herd of Przewalskis. A few years ago, to fulfil a campaign pledge to a donor who happened to want to develop land occupied by some stables, the New York mayor Bill de Blasio attempted to ban the few remaining Central Park carriage horses, calling their use ‘inhumane’. His proposal failed when their drivers protested that they would lose their livelihoods. De Blasio’s counterproposal? To replace the horses with a fleet of vintage cars.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.