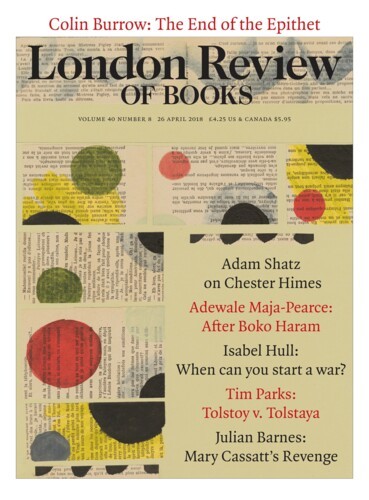

What you can paint depends on what you are allowed to see, which may be controlled by regulation or social convention. So, for instance, at the Paris Opéra in the 1870s, women were not under any circumstances permitted to sit in the orchestre. And they could only sit in the parterre, or rear stalls, if accompanied by a man. An unaccompanied woman could only attend a matinée. At evening performances, women were allowed to attend in pairs or groups, when they might sit together in the upper loges, or boxes. And needless to say, no respectable woman was allowed backstage, where only the entitled male – a self-declared ‘connoisseur’ of women, whether as lecher, or in rare cases, as painter – might tread. These baroque rules explain some painted facts: Degas had the freedom to place his focus anywhere in the theatre, the viewer’s nose and eye one moment butting up against a giant bassoon, the next swirling round a ballerina dans les coulisses. Whereas Mary Cassatt, in paint as in person, was restricted to the view from the loge. This is what her painting In the Loge shows: a woman in black sitting in a theatre box, holding a fan, leaning on the balcony rail and training her opera glasses on the (out-of-shot) stage. However, in the background, a curve of boxes away, a man is blatantly training his binoculars on her. It’s as if he’s telling her: don’t forget that the male gaze rules here, my good woman.

Cassatt faced similar obstacles in her art training: as a woman, she could study privately under well-known artists – Gérôme, Chaplin, Couture – but she was not allowed to follow courses at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Sometimes, being foreign was an additional handicap: both Cassatt and Pissarro were occasionally excluded from shows on grounds of nationality. However, Cassatt’s position was not all disadvantage. She came from a very supportive and very rich Pittsburgh family (her father could happily retire at 42); she was well educated, well travelled, trilingual and forceful of character; she could afford to visit Rome, Parma, Madrid and the Low Countries in search of great masters. Money is never neutral– as other painters were well aware. Here is Camille Pissarro in Paris reporting to his son Lucien in Bayswater on his visit to ‘Mlle Cassatt’ in April 1891:

I want to tell you about the colour prints she is planning to exhibit … You remember those trials you made at Eragny? Well, Mlle Cassatt has managed it all admirably: the fine, delicate matt tone, without any grubbiness or staining, an adorable blue and fresh shades of pink. Well, so what did we lack in order to succeed as she has? … Money, yes, just a bit of money.

The tone is rueful rather than envious: on the whole the Impressionists – like most young artists starting out in bands – were generous to one another. Nevertheless, there follows a list of what the Pissarros could not afford: copper plates, an aquatint box, plus the services of a printer. With them, like Cassatt (and with her talent), they might produce work as beautiful as the Japanese.

For much of her life, Mary Cassatt was the American face of French Impressionism; up until the 1920s she was better known in the US than Degas was. She brought the good news from Europe in another way too: as intermediary, go-between and tipster. She encouraged both her brother Alexander and her lifelong friend Louisine Elder to start collecting: Elder’s first purchase was Degas’s Rehearsal of the Ballet, which with Cassatt’s In the Loge became the earliest important Impressionist works displayed in the US. Elder was to become the biggest collector of Degas. Cassatt also worked with the great Parisian dealers of the time – Durand-Ruel, who opened a New York branch in 1888, and later Vollard. She was one of the main reasons Impressionist pictures are now to be found in public museums across the Midwestern cities. Back then, the collectors were chasing Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Degas. Nowadays, the transnational squillionnaires who have replaced those steel and railroad barons seek personal validation through contact with a different Big Four – Warhol, Basquiat, Koons and Hirst – their eye chaperoned not by a practitioner like Cassatt but by sleek art advisers who can run the numbers, and often take a startling cut on deals. You almost feel nostalgic for Sinclair Lewis’s Dodsworth, whose industrial riches allowed him the Biedermeier carpet, the grand library of partly read books, the cabinet of sophisticated drinks and ‘the oak-framed fireplace with a Mary Cassatt portrait of children above it’.

Cassatt lived for sixty years in France and is buried there; she was the second woman to show with the Impressionists (Berthe Morisot being the first), and the only foreigner. In 1904, she was given the Légion d’honneur (not the first woman artist to get it – that had been Rosa Bonheur in 1865 – but undoubtedly the first foreign woman artist). Yet 92 years have passed between her death and her first posthumous exhibition in France: 52 works in rather cramped rooms upstairs at the Musée Jacquemart-André. Morisot – who hasn’t had a proper French show since 1941 – will get a larger exhibition later this year, travelling from Philadelphia to Dallas and ending next year at the Musée d’Orsay.

When the Impressionists launched their first group exhibition in 1874, Le Figaro called it a collaboration between ‘five or six lunatics, one of whom is a woman’. It’s hard to tell if Morisot, as the woman, is being partially excused lunacy, or judged the loonier for it. Cassatt’s sex would in turn result in her being boxed by critical opinion and diminished into a mere pupil of Degas. Here is Edmond de Goncourt, who hated much of the modern world, and especially the modern art world, ranting away in March 1890:

The newspapers’ admiration for Mlle Cassatt’s etchings is enough to make one die laughing. Etchings which contain a small area of success, down there in one corner, surrounded by heavily crass draughtsmanship and maladroit gouging. Truly, our age has given itself over to the religion of Botch. The high pontiff of Botch is Degas, and its little choirgirl is Mlle Cassatt.

Cassatt was aware of, and resented, being historicised in this way during her own lifetime. She was never Degas’s pupil, nominal or metaphorical. She was 33 and artistically well formed when they first met; he approached her as a result of seeing one of her pictures at the Salon, and invited her to show with the Impressionists (though he preferred the term ‘Independent’ or ‘Realist’); and it was he who said of her: ‘There is someone who feels as I do.’ At one point, they considered taking a trip across America together. In 1886, after the final Impressionist Exhibition, they had a symbolic picture swap – like pressing bloodied palms together; he got Cassatt’s Girl Arranging Her Hair, and she got his Woman in a Shallow Tub. They were serious equals in a visual conversation; they discussed technique and form rather than artistic selfhood; you would not mistake her mature work for his, either in subject or in process. And when they quarrelled, she quarrelled with him as much as he quarrelled with her; and though they inevitably fell out over the Dreyfus Affair, this was one fracture, unlike most, which Degas cared to repair. They both became more intractable with age, and both suffered a catastrophic loss of eyesight (hers due to cataracts and diabetes); she faced the dying of the light with more philosophy. When Degas died, he was found to own more than a hundred of Cassatt’s prints – including 13 impressions of The Visitor – plus oils and pastels. Their friendship gives further evidence against the idle blanking of Degas as a ‘misogynist’.

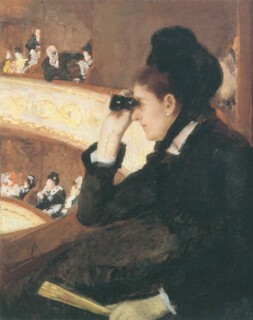

Not that being Degas’s friend was ever easy. His compliments were rare, hard-earned, and invariably flavoured with a little vinegar. And their relationship got off to an awkward start. In 1877-78, shortly after they met, she did her self-portrait in gouache and watercolour while he did her portrait in oil. She is wearing the same hat and dress in each picture, so they were certainly begun at the same time. But the resemblance ends there. Cassatt’s Cassatt is thirtyish, fresh-faced, erect, cheerful, in front of a pale daffodil background. Degas’s Cassatt is leaning forward on a small chair, with a wry expression and a slightly lop-sided chin. She is holding, fanned out, what are probably photographs; but the overall dark tones and hunched posture suggest a Gypsy fortune-teller spreading her cards. Also, this woman might be in her fifties. It is a powerful portrait, if not to (or exactly of) the sitter herself, and you can see why, when trying to sell it to Durand-Ruel in 1912-13, Cassatt wrote: ‘It has artistic qualities but it is painful to me and represents me as a person so repugnant that I do not want anyone to know that I posed for it.’ Despite this, she continued to pose for him if ‘the model cannot seem to get his idea’. And a decade later, perhaps in reparation, Degas devoted his greatest series of etchings, as well as drawings and two paintings, to the theme of ‘Mary Cassatt at the Louvre’. He depicts her (accompanied by her seated sister Lydia) as an elegant, striking figure leaning on an umbrella, back turned against us, deeply engaged with the contents of the Etruscan Gallery.

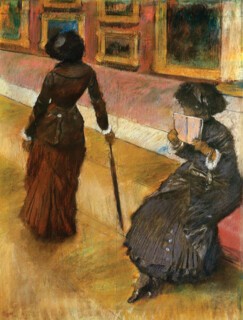

Now, with time and a shift of art-historical wind, we may see Cassatt a little more clearly, and a little more as herself. She is, largely, a painter of the great indoors, the here and now, and of women’s space within it. She does not do landscape or nature – the urban park and the boating lake are as far as that goes; nor does she give us action, history, myth, still life, houses, horses, sunsets or those forbidden parts of the Opéra. She does not do men much, though her double portrait of her brother Alexander with his son Robert, the boy sitting on the arm of his father’s armchair, their black suits blending into one and their button-black eyes popping in parallel towards some unknown object (a joint-television gaze from pre-television times) makes us wish she had portrayed the opposite sex more. She does mothers and babies with an acute eye for the weight and fall of an infant’s flesh, and an acute sense of the weight and fall of an infant’s mood. She made a series of colour prints whose limpidity, grace and line echo and learn from the Japanese without appearing in any way subservient (though it would be good to know what the Japanese thought, and think, about them). She did some rather weak pictures of the big-hatted daughters of friends. And she did several one-off paintings – like Little Girl in a Blue Armchair and In the Loge – whose power has never faded. It is an indicator of Cassatt’s return to wider fashion that Simon Schama included two of her ‘Japanese’ prints in an episode of the TV show Civilisations, while in a later one David Olusoga brought In the Loge to his argument.

In Little Girl in a Blue Armchair (1877-78) a girl of perhaps six or seven half-sits, half-lies, in large armchair. She looks as if she has originally been posed, in a white lacy dress with tartan accessories, but has slipped from that pose. Her dress has ridden up; her legs, being too short to bend where the armchair bends, stick out towards us. She has her left hand jammed behind her neck, and her right hand tucked between her thigh and the chair arm: these look like desperate measures on her part to obey the instruction to keep still. She doesn’t look comfortable. Why should she? She has been placed for inspection in a giant chair and told not to move. There are three other large blue adult chairs in a curve behind her. On the nearest sits a small brown dog, paws tucked in, eyes closed. This is a witty touch. The dog’s posture mocks that of the girl. Look! it says, I can do this posing stuff all day.

Cassatt’s children are modern children, from the ‘Independent, Realist’ school. If Degas can somehow show us the weight of a head of female hair, Cassatt can show us the weight of a whole baby. In Woman Sitting with a Child in Her Arms (1889-90) a mother in a chair with her back to us holds a naked, sleepy infant, its head sagging against its own uncomfortable arm. The child is facing us, but quite indifferent, its eyelids about to drop; we feel as if sleepiness has added volume to the baby’s flesh, and with it extra weight to the mother’s shoulder. Elsewhere, there are babies sometimes half in their mother’s world, or wholly in their own; never in ours. This one, forefinger in mouth, has the air of a Posy Simmonds mite; this one hides behind his mother’s neck and his own fist, peering suspiciously at the viewer; this one, face aligned next to its mother’s, seems to have sucked the life out of her, the mother trying to disguise exhaustion as thoughtfulness. In Jenny Cassatt and Her Son Gardner (1895-96), Mary’s sister-in-law, a sturdily no-nonsense figure, grasps her largeish black-clad boy to her bosom with a meaty hand. The boy squirms his head round to glare at us. His expression says either a) how dare you interfere with this intimacy with my mother; or b) yes, I know I’m much too big to be cuddled and I’m embarrassed to be caught like this, but can’t you see how fierce Mamma is; or c) both at the same time.

Given the variety and individuality of these mother-and-child couplings, it comes as a surprise to learn that by the 1890s Cassatt was being held up in France as ‘the painter of the Modern Madonna’. In George Lecomte’s words of 1892: ‘When Miss Cassatt represents mothers and children, her compositions have a nobility to them, conveying the highest characteristics of the HOLY FAMILY, but a Holy Family of modern times.’ Where did that idea come from? Perhaps it leaked across from the Catholic revival in French society after the catastrophes of 1870-71. Perhaps it is just loose terminology mixed with sentimentality. But it is hardly pedantic to point out that some of these supposed Madonnas seem to have given birth to girl saviours; also, that there is a distinct absence of Joseph, let alone ox and ass and supporting saints. Cassatt, a lifelong feminist, displays no overt or covert religious purpose in these or any other pictures. Certainly, she knew her Rubens and her Correggio; and at times introduced reminders from art history. So, in The Oval Mirror (1899), the mother supports and presents the uncircumcised boy-child in a standing position, while behind the child’s head the mirror’s circle gives the sign of a halo.

But this remains a formal allusion rather than an indicator of religious content. Degas made a typically sardonic crack about The Oval Mirror: ‘It’s the baby Jesus with his English governess.’ In France at that time English governesses were not thought of as having the grace and serenity of the Virgin Mary. The New York Times concurred in a brief review of 1903: ‘The Cassatt oils and pastels. Ugly women in curious gowns and babies in no gowns at all.’ And so Cassatt was caught in a strange pincer movement, on the one hand falsely vaunted for quasi-idealism, and on the other damned for truthfulness. It has often been the fate of women artists to suffer forked praise and the backhanded compliment. Huysmans, facing Cassatt’s child portraits for the first time at the Impressionist Exhibition of 1881, wrote that he had never before seen modern children painted with such charm and naturalness: ‘Only woman has the proper skill to paint childhood.’ That sounds complimentary enough, until he adds, ‘Only a woman knows how to pose the child, to dress it, and to put in pins without pricking herself.’ Get back in your (sewing) box, woman! But Mary Cassatt was never one for being put in a box; and she also knew some of the pleasures of time’s quiet revenge. In 1915, her old friend Louisine Elder organised a show at Knoedler’s in New York. From Paris, Cassatt helped her include in it 24 of Degas’s works, and 19 of her own; by sharing walls with him, as she put it to Louisine, ‘I can show that I don’t copy him in this age of copying.’ But a more ironic source of satisfaction lay in the exhibition’s purpose: to raise funds for the cause of women’s suffrage. Cassatt observed to Louisine how ‘piquant’ this was ‘considering Degas’s opinions’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.