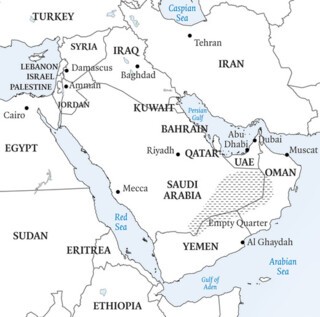

On the night flight down from Kuwait, along the Saudi coast past Bahrain, Qatar and the UAE, a seafront once dotted with tiny fishing villages glitters like a string of pearls. Needle-thin skyscrapers soar above the desert. Doha’s bay shimmers in purple, as if daubed in lipstick the colour of the Qatari flag. In the restaurants of Dubai, a city built on a Gotham-like scale, the wealthy eat oysters imported from France ($15 each at Atmosphere, the highest restaurant in the world, a quarter of a mile up the Burj Khalifa tower).

The Gulf dynasties resemble the despotic families of 15th-century Italy and their city states. The earlier set of potentates owed their rise to trade, the more recent to oil. The heyday of the Gulf rulers threatens to be ephemeral. In their latest piece of brinkmanship, they have ruptured local alliances and sought protection from foreign powers. Petty squabbling – first over interests abroad, then at home – threatens to hasten their decline.

As with the Renaissance city states, sleepy creeks have been transformed into world-renowned cities. At fabulous expense, the Gulf rulers set out to leapfrog centuries of development by furnishing their realms with the starchitecture of opera houses and art galleries and grafting offshoots of American universities onto their education systems. Sultan Qaboos of Oman refers to his own reign as ‘the Renaissance’. They care nothing for the past. Sultan Qaboos flattened Muscat’s old city. Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammad bin Salman, who trained as a competition lawyer, has announced a plan to build a self-sustaining high-tech city, full of robots and covering an area 15 times the size of London, on the Red Sea coast. ‘All Gulf rulers are erasing history in the name of creating mega-cities,’ Ahmed Mater, a Saudi photographer, told me when we met in his studio in Jeddah, but the Saudi treatment of Mecca has been the most damaging. When the Prophet Muhammad took the city, he threw out the idols but largely preserved the shrines and edifices. The Al Sauds, motivated by greed and a version of Islam that espouses the wiping out of tradition to recover a lost purity, have demolished 1400 years of construction since taking power ninety years ago. For a time, the official emblem of Mecca was a bulldozer. The Kaaba aside, nothing of the old city remains. Monuments to commercial gods stand in place of shrines and mosques, some of them as old as the Prophet.

Mater has recorded the demolition in his recently published album, diplomatically entitled Desert of Pharan: Unofficial Histories behind the Mass Expansion of Mecca.* His studio is cluttered with memorabilia salvaged from flea markets. One photograph was taken from a Hilton hotel tower. A red rose in a thin vase on a coffee table dominates the foreground. The Great Mosque and the Kaaba lie in the background, out of focus hundreds of metres below. Seen from such a height, they look like a shopping centre.

The same photograph hangs above the desk of Hamza Serafi in Athr (Remnants), his art gallery in Jeddah. His father made a fortune developing Mount Omar, a hill beside the Great Mosque. Together with the shrine of the third caliph, the mosque was levelled so that the foundations for a cluster of towering hotels could be laid. ‘We reduced the organic growth of a thousand years into a concrete jungle,’ Serafi told me as he showed me round his gallery. The works on display were testimony to his desire to repair the damage. Hanging from the walls were paper fighter jets made from the pages of old passports. Three gramophones played Beethoven’s symphonies at different tempos. Serafi’s world was out of sync. There were picture postcards, with woollen figurines of refugees woven onto photos of tourist resorts. ‘We let barbarians erase our history,’ he said. ‘We’re all refugees displaced from the past.’

The Arabian peninsula’s modernist architecture is a dramatic illustration of the new order’s break with tradition. Yemen aside, the squat villages, the small oasis encampments and the fairy-tale mud houses decorated with whitewash as delicate as icing sugar have been replaced by skyscrapers that emphasise the smallness of the individual. Power has been similarly transformed. Much as the communes running Italy’s city states evolved into dynasties, Arabia’s bedouin tribal federations have been replaced by stratified monarchies. The Al Sauds of Saudi Arabia, the Nahayans of Abu Dhabi, the Maktoums of Dubai, the Sabahs of Kuwait and the Thanis of Qatar mirror the Borgias of Rome, the Medicis of Florence, the Sforzas of Milan, the Estes of Ferrara. The three pillars of the old order – clans, tribes and clerics – are tumbling down.

It is in Saudi Arabia, again, that the transition is most striking. Since 1953, the succession had passed horizontally from brother to brother among the many sons of the kingdom’s founder, Ibn Saud. Each nuclear family in the clan has had a turn at the top. Titles, portfolios and assets were divvied up among multiple heirs. Decision-making by consensus was painfully slow, but the separate clusters of power created a system of checks and balances. When the current king, Salman, made his son, Prince Mohammad, crown prince last year, he flipped the succession vertically, from father to son in his own line. The new monarchy is absolute.

Today’s Gulf rulers have more in common with Saddam Hussein’s bullish totalitarianism than with the tribal collective. In place of societies where elders compromised, young rulers now govern with the conviction of revolutionaries. Qatar’s emir, Tamim Al Thani, is 37. Prince Mohammad, who has day-to-day control of the kingdom, is 32. Across the peninsula, the majlis, the tribal equivalent of a fractious town-hall meeting, has been reduced to a perfunctory ceremony, if not abolished. Saudi petitioners no longer throng through the royal gates on Tuesdays and Fridays to share a meal with their leaders. The new rulers appear to their public on ubiquitous billboards, but are out of reach in person. Communication is one-way only. The old tribal codes of hospitality and chivalry have been ditched. Family feuds between tribal elders have always been commonplace, but the reason Gulf Arabs find the Saudis’ current spat with Qatar so shocking is that it highlights how far the tribes’ status has slipped. By closing their borders and expelling Qataris, the Saudis reduced kinsmen to statistics. Tribes were fractured, unable to prevent the separation of Qatari wives from Saudi husbands. Qatari camels grazing on Saudi pastures were driven into the Qatari desert to dehydrate and die.

‘He who quells disorder by a very few signal examples [of cruelty] will in the end be more merciful than he who from too great leniency permits things to take their course and so to result in rapine and bloodshed,’ Machiavelli wrote in The Prince. On his path to power, Mohammad bin Salman executed at least one royal and imprisoned hundreds more. Unlike his elderly uncle, the previous king, Abdullah, who wooed and cosseted potential adversaries, Prince Mohammad is a bruiser who gets the job done. He has ended the culture of royal impunity (his immediate relatives aside), pruned the sprawling House of Saud and stripped likely pretenders of their assets and patronage base. Last July he pushed aside his cousin, the then crown prince, Muhammad bin Naif, who’d been called ‘the cat with nine lives’ after surviving an assassination attempt by an al-Qaida suicide bomber who had stuffed his rectum with explosives.

The family council’s approval was far from unanimous. Footage went viral on social media of Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, another former crown prince, holding court beneath portraits of the state’s founder and the current king; a third space was empty, indicating Abdulaziz’s refusal to accept the new crown prince. His sons fled to London and began backbiting against the young upstart. Some senior royals publicised a hashtag seeking bin Naif’s restoration.

That dissent probably prompted the far larger round-up in November. In the name of tackling corruption, Prince Mohammad summoned some two hundred princes and moguls who naively regarded themselves as too important to be touched, and locked them up in Riyadh’s most luxurious hotel, the Ritz-Carlton. They included Mutaib bin Abdullah, the son of the previous king and the head of the National Guard, a force of more than 100,000 drawn from the tribes. There were several media barons, including Walid Ibrahim, a brother-in-law of King Fahd, who founded MBC, the first Arabic satellite channel, and then al-Arabiya, Saudi Arabia’s answer to Al Jazeera; and Al-Waleed bin Talal, like Mohammad a grandson of the kingdom’s founder, who owns Rotana, another satellite channel, and has long-standing ties with Rupert Murdoch. After two months, most were released, but some who refused to meet their ransom demands are still being detained.

After the Ritz-Carlton round-up, almost all the kingdom’s journalists followed Mohammad’s line. Revamped with the latest technology, the satellite channels broadcast martial anthems and footage of the crown prince’s special forces in training. Saud al-Qahtani, his media adviser, tweeted constant paeans of praise. His own publishing house – the Middle East’s largest, the Saudi Research and Marketing Group – struck a deal with international media outlets, including Bloomberg, to amplify his narrative. For the prince the flattery was seductive. Mohammad is said to like his courtiers to call him Iskander, Arabic for Alexander the Great, and to read tales of his exploits in bed. To deal with remaining naysayers, he decreed that criticism of the king or the crown prince be treated as an act of terror. A new state security service, modelled on Egypt’s Amn El Dawla, an internal intelligence agency, monitors mobile phone activity to identify troublemakers and bring them in for questioning. ‘I’m retiring from twitter to spend time with my family,’ an acerbic political science professor posted after deleting his tweets.

Like the peninsula’s other sovereigns, Mohammad has also turned on the clergy to enhance his temporal power. Oman’s sultan abolished the Ibadite imamate and seized its oilfields in 1957. Republicans overthrew Yemen’s Zaydi imamate in 1962. Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, crown prince and de facto ruler of the UAE, banned the Muslim Brothers in 2014. Bahrain’s king revoked the citizenship of the island’s leading Shia cleric in 2016. Belatedly, Prince Mohammad has stripped the Saudi religious police of their rights of arrest and revoked the clerics’ hitherto sacrosanct control of public space. He is dismantling the rules on gender segregation. Women can now mingle with men in restaurants, at concerts and in the family sections of football stadiums. They are entering the workplace in greater numbers and from this summer will be allowed to drive cars. Women flouting the dress code aren’t inevitably punished. After a woman posted a selfie of herself walking through the old city of Ushaiqer, an ultra-conservative town in the puritanical stronghold of Nejd, unveiled, dressed in a mini-skirt and exposing her midriff, she was arrested but released without charge the following day. The crown prince has quashed the ban on cinemas and financed resorts to be built on fifty untouched islands in the Red Sea, which will be subject, officials say, to ‘independent laws and a regulatory framework developed and managed by a private committee’ – in other words, Sharia-lite codes. (Tellingly, when I met him in 2016, he recited a Saying of the Prophet prohibiting non-Muslim places of worship on the peninsula, not the islands.) For the first time, the kingdom will issue tourist visas, including for unchaperoned women.

But the kingdom’s transition is still a work in progress. The authorities have deleted Quranic verses in support of visiting jihad on unbelievers and polytheists from primary school textbooks, but have been slower to edit high school equivalents. Headteachers forbid Afghan veterans from entering playgrounds during break to recruit pupils, but some lecturers still inspire teenagers to seek the glory their great-grandfathers won as the heroic mujahedin who secured the kingdom for Ibn Saud. For young people emasculated by the crib-to-coffin oil-funded welfare handed out by the Saudi state, IS’s war in Syria has had the appeal of an adventure holiday. More than 3800 Saudis have enlisted, according to one Saudi courtier. In the event of their martyrdom, families hold wakes and there is sometimes a good deal of local sympathy. Satellite channels continue to promote the cause. ‘We fight because we are Muslims in accordance with the ulama,’ a speaker declared on al-Burhan, which remains a vehemently sectarian outlet.

Previous attempts at Saudi modernisation have not ended happily. In the 1950s, King Saud, the founder’s second son, sought to establish primogeniture, create a constitutional monarchy and appoint a commoner as prime minister. Fearing for their inheritance, his brothers converged to depose him and entered into alliances with religious hardliners. Cinema, music and concerts were banned, morality police took control of the streets and the kingdom retreated into obscurantism. Some people warn that the centralisation of Saudi authority is once again fostering dynastic opposition and risks destabilising the kingdom. There have been signs of rebellion, including an attack on one of the crown prince’s palaces: a man armed with Kalashnikovs and Molotov cocktails killed two members of the Royal Guard before being shot dead. Since his promotion, Prince Mohammad has avoided leaving the country, even for events like the G20 summit. There’s talk of a trip to Washington, but increasingly he seems to be confined to the safety of the Defence Ministry, which he still runs. Fearful of reprisals, opponents are either in hiding or fleeing abroad: the new arrivals can be found on West London industrial estates and in the studios of Arabi21, one of Qatar’s latest news outlets.

That said , the more common response to the prince is confusion. ‘Everything we stood for seems open to question,’ a young Saudi academic says. ‘If Sharia does not apply to tourist resorts, why should it apply elsewhere?’ Some seem torn between loyalty to the flag, with its declaration of faith underlined by a sword, and the national day, when last year women mixed with men at public concerts. Prince Mohammad’s embrace of tolerance and his establishment of an anti-terror coalition of 41 Islamic states – the alliance held its first meeting in November in Riyadh – are hard to take in for those who were taught that jihad was a fundamental pillar of Islam. ‘No to terrorism and wayward thoughts,’ a government banner on a flyover in the Salafist stronghold of Buraydah declares. As if by way of rebuttal, someone has pinned the Saudi flag alongside it.

Such indirect criticism falls far short of revolt. Perhaps his detractors know that the kingdom can’t afford another failed experiment in modernisation. With oil price rises capped by America’s shale production and with rapid advances in fuel-cell technology in the offing, oil revenues may never again cover state expenditure. The kingdom has no choice but to diversify its economy. Young Saudis, who constitute the majority, have been particularly enthusiastic about Mohammad’s transformation of an ultra-conservative sheikhdom into a 21st-century state, and on Vision 2030, his programme – vague in many of its particulars – for a post-oil future. For some, the Gulf Spring appears to have come. But despite the populism, his helter-skelter changes have only consolidated power in a reduced number of hands. Unlike the Arab Spring, which started on the street, Saudi Arabia’s changes are top-down. Mohammad’s multiple media platforms celebrate the demonstrations calling for freedom, democracy and justice which have swept the streets of Iran. But they condemn the dissent caused by increases in petrol prices and cuts to subsidies at home.

Until recently, Saudi citizens – in common with those in large parts of the Gulf – have barely been taxed. This is starting to change: at the beginning of this year, as part of the drive to diversify the economy, Saudi Arabia and the UAE introduced 5 per cent vat on most goods and services. Increasingly Gulf nationals are paying for their own government. But in exchange they are getting personal liberties not political representation. The Gulf’s liberalism is distinctly illiberal.

Prince Mohammad isn’t the only or the worst offender. The UAE, perhaps the most totalitarian of the Gulf states, brooks no criticism. Associations advocating heritage preservation are banned. Migrant workers with the gall to seek better labour conditions are sent packing. Last year, Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a political science professor, disappeared for ten days after tweeting about freedom of speech. A 15-year jail sentence awaits anyone caught expressing sympathy with Qatar. A decade ago the UAE was viewed as the least politically developed Arab state, today it tops the list of countries where Arabs most want to live.

In the past Qatar preferred soft power prestige investments to buying weapons from the West. (In 2015, David Cameron went to Doha at BAE’s behest to sell British warplanes, and returned empty-handed.) But it discovered to its cost that Western powers would be half-hearted in its defence unless it used some of its $340 billion sovereign wealth fund to buy Western arms. When the spat between Qatar and Saudi Arabia began, Donald Trump sided with the Saudis, publicly berating Qatar’s emir for supporting terrorism and not buying America’s ‘beautiful military equipment’. Western countries only began applying pressure on Saudi Arabia to defuse the crisis after Qatar’s defence minister, Khalid al-Atiyah, toured London, Paris and Washington. By January, he had purchased 24 Typhoon warplanes for £6 billion, 24 French Rafale jets and 36 American F-15s, increasing the size of his country’s airforce sevenfold, and agreed to pay for an upgrade of al-Udeid, already America’s largest foreign airbase. With the deals in the bag, Trump about-turned and thanked Qatar for its efforts to combat terrorism.

This is nothing new. Contracts for arms manufacturers have always overridden bills of rights. Ministers visiting from the West praise Gulf governments for their efforts to wean themselves off a dependence on oil, and to turn sheikhdoms into modern bureaucracies. Europeans single out the UAE for favour without a word on the absence of democracy: alone in the Arab world, Emiratis are allowed visa-free access by the EU. Bahrain, once the Gulf’s most vibrant democracy, avoids censure for its mounting repression. Last year its king proscribed the island’s last opposition party and its last independent paper. Qatar, which presents itself as a beacon in reactionary waters, bans unions and political parties. As a senior Saudi official notes, ‘if Qatar cares so much about freedom and democracy, why haven’t they introduced it at home?’

Arms contractors are not alone in selling flights of fancy. In their bid to achieve global stature, the sheikhdoms imported Asian labourers to build their cities, and Western pleasure-seekers to fill them. They purchased prime sports fixtures – the 2022 World Cup is to be held in Qatar – and built vast ports and airports to serve as hubs between East and West. But despite their vast wealth, their ambitions have been limited by minuscule populations, a lack of raw materials bar oil, and by the big brother among them, Saudi Arabia, which would always block any westward expansion on the part of its lesser neighbours.

But the new despots have increasingly sought grandeur abroad. Qatar was the first to extend itself, latching onto the coat-tails of the Muslim Brotherhood. The Al Thanis offered refuge to its leaders, including its spiritual mentor, Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi. Funding, salaries, diplomatic passports, a platform on Al Jazeera and arms solidified the alliance. The Arab Spring gave Qatar its opportunity. Long-suppressed Islamist movements filled the vacuum created by the collapse of the Middle East’s autocrats, and Qatar rushed to their aid. It financed election campaigns and armed militias. When Gaddafi was toppled in Libya, its agents festooned Tripoli squares with Qatari flags and donated police cars painted the colours of the Qatari flag. The Al Thanis, the rulers of 300,000 Qataris, now had influence in Syria, Libya, Tunisia and Egypt, countries with a combined population of 132 million.

Qatar’s gains encouraged the Gulf’s other potentates to follow suit. A decade ago, Dubai Ports, which manages the Middle East’s largest port, Jebel Ali, renamed itself DP World. By 2016, it was administering ports in 39 countries. Six months after DP World signed an agreement to run Berbara, an old Ottoman port on the Horn of Africa, the UAE army leased an adjoining military base. Under the command of an Australian general, Emirati expeditionary forces launched a series of amphibious landings to capture ports along the Yemeni coast. It also rented an airbase in Eritrea and dispatched its planes to the Mediterranean to bolster Field Marshall Khalifa Haftar’s army in eastern Libya.

The Saudi approach is somewhat different. In interviews, Prince Mohammad frequently alludes to his grandfather, Ibn Saud, who carved out a kingdom by invading his neighbours. But contrary to his image as a would-be Iskandar, Prince Mohammad’s foreign policy is characterised by retrenchment (with the notable exception of Yemen). Perhaps he has territory and problems enough to deal with at home. He has cut ties with mujahedin not only on faraway fronts in Afghanistan and Bosnia but also in Syria. He has repaired fences across Islam’s schism: he has sat smiling with Iraq’s Shia leaders, clerics among them, and reopened the road to Iraq closed since Kuwait’s invasion in 1990. He has renewed long-severed investment to Oman’s Ibadite leaders, and discussed opening a new but never used road through the Empty Quarter to the Indian Ocean. Many of his proxies in Yemen, including the country’s chief of staff, have been Zaydis, not Sunnis. He has received Lebanon’s Maronite patriarch in Riyadh and more than any Saudi leader before him has made advances to Israel. Even on Qatar, he has been less bellicose than King Abdullah was in his dispute with Bahrain: unlike the former king, he hasn’t sent in tanks. But the aggressive moves Mohammad has launched often seem ham-fisted and rash. The resignation he forced on Saad Hariri, Lebanon’s prime minister (and a Saudi citizen), backfired spectacularly after Western leaders joined Lebanese politicians in demanding his release from house arrest. Mohammad’s overtures to Israel unnerved Jordan’s Hashemites, who, having lost two Muslim holy cities to Ibn Saud in the 1920s, suspected the prince had designs on a third, Jerusalem, where they still had special status.

And Qatar has dug in its heels. The embargo that Saudi Arabia, the Emirates and Bahrain declared in July has achieved none of its 13 goals. One was to close Al Jazeera, but Qatar’s satellite channel still relentlessly mocks Prince Mohammad’s foreign policies, particularly in Yemen. Qatar is the world’s richest per capita state, and it is weathering the embargo well. Turkish contractors have taken over the work of Saudi construction magnates and Iranian food has replaced the perishable goods that used to come over the Saudi border. Instead of block-booking hotels in Dubai for the teams competing in the 2022 World Cup, Qatar has approached the Iranian resort of Kish Island.

Prince Mohammad’s sole war to date, on Yemen, may not be quite the strategic disaster his detractors claim. Editorials worldwide have denounced the spectacle of the Arab world’s richest state bombing the poorest one to the brink of starvation. Increasingly, Mohammad is being cast as the impetuous bull in the region’s china shop, not the reformer he would like to be seen as. Ballistic missiles from Yemen are landing in Riyadh, puncturing the belief that the kingdom is unassailable. But in one important respect, Mohammad has succeeded where his grandfather failed. British colonial rule of Oman and South Yemen repeatedly thwarted Ibn Saud’s hopes of breaking free of the maritime chokepoints of the Gulf and the Red Sea and advancing to the Indian Ocean. By contrast, Mohammad’s bombardment of Yemen’s mountainous north-west has kept the Houthi rebels locked down, while leaving Saudi forces free to march along the old incense route through the Hadramawt. In November 2017, with minimal fanfare, he finally moved on the port of Al Ghaydah in Yemen’s south-east and reached the open sea.

Success can have its drawbacks. The Arabian peninsula is chock-a-block with ambitious despots wary of one another’s triumphs. Bahrain worries it will lose its role as Saudi Arabia’s weekend playpen once the kingdom opens its cinemas and resorts. Dubai’s hoteliers predict a spate of cancellations once Saudi women no longer need to travel to the UAE to go to concerts. There are simply too many international hotels, sports venues, airports and ports for so small a population. December’s normally glitzy Camel Market in the UAE was a distinctly tawdry affair, with perhaps a quarter of the normal turnout of 250,000 camels. There are too many rival shows. Supply is outstripping demand.

As competition intensifies, so do internal tensions. The Gulf Co-operation Council, formed in 1981 in response to Iran’s revolution, is fragmenting. Qatar and the UAE are waging a power struggle, under a veneer of ideology, aimed at torpedoing one another’s initiatives. After Qatar financed the election campaign that brought Mohamed Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood president, to power in Egypt, the UAE sponsored an army general to unseat him. And all the Gulf states are still buying weapons: collectively, they spend more per capita on arms than anywhere else in the world. From 2012 to 2016, Saudi Arabia and the UAE were the second and third largest arms importers globally, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. In November, Dubai’s outspoken security chief, Dhahi Khalfan, called for the ‘bombing’ of Al Jazeera. In January, UAE officials accused Qatari warplanes of buzzing two Emirati airliners.

So far, the sheikhdoms have held back from military confrontation, at least at home. But even without war, the reputational damage to the region has been immense. As in 1990, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, individual GCC members have abandoned talk of integration and common defence and sought protection elsewhere. Most still look west. But Gulf sheikhs are also mindful of America’s waning interest in a costly military presence. If Kuwait was invaded again, Gulf leaders worry, would America send in troops?

In search of alternatives, they are soliciting support from the region’s non-Arab states for the first time since the fall of the shah. Last year, the presidents of Iran and Turkey made repeated tours of the region. Between May and November, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Kuwait three times, and opened its new Turkish-built airport as well as a new military base in Qatar – Turkey’s first outpost in the Gulf since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Turkey and Persia are hardly newcomers. But since their rise in the 18th century, the Al Sauds have stood as an Arab bulwark against Turkish encroachments. It would be a singular indictment of Prince Mohammad if he was blamed for engineering the crises that brought them back. ‘We’re seeing the splintering of the counter-revolutionary fortress,’ says Moulay Hicham, a Harvard academic related to the Saudi king. Power struggles between city-state despots ended Italy’s renaissance by opening them to foreign would-be protectors. It could happen in Arabia too.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.