There was once a time when, in the eyes of advanced American taste-makers, Grant Wood led the list of home-grown artists who ought to be dismissed. Clement Greenberg, for example, used his column in the Nation to make it clear that nothing by Wood and his fellow figurative painters, not even their most successful compositions, was anything like as interesting as an unsuccessful picture by an average abstractionist.

In normal circumstances Greenberg’s verdict isn’t one that British viewers can easily put to the test. Though Wood himself made four trips to Europe, his paintings seldom leave home. But now seven of his pictures are at the centre of America after the Fall: Painting in the 1930s at the Royal Academy (until 4 June). Setting aside their odd role in the opening skirmishes around American abstraction, they provide one excellent reason the show should be seen.

The other is its unexpected relevance, given the surprise election of Donald Trump. It is hard to forget that these paintings were all produced during a decade deeply marked by loss: lost wages, lost savings, lost homes and farms and lives and futures. Inevitably – necessarily – art had a role in answering to destruction so widespread that Wallace Stevens described it in 1937 as a ‘generation’s dream, aviled/in the mud’. What had disappeared was not some past state of innocence: instead the decade of the 1930s produced paintings that showed the very idea of innocence to be a fiction, a myth mud-spattered from the start. In this new world, nothing could be trusted or taken for granted. And when the past has been exposed as a fiction, the present can only struggle to discover alternative values and forms.

At the Royal Academy, this struggle is on blatant display. In Haunted House (1930), by the New York-based Morris Kantor, it takes place inside an old-time Cape Cod parlour, complete with talismanic pictures (a colonial worthy, a schooner under sail) and ladder-back chairs. It’s the perfect place for a haunting, and Kantor obliges, summoning a shadowy spectre, a thing of dusky vapours within which float visions of a sleeping village, wafted in from a story by Poe.

If there is something unsettling in the way Kantor, who was born in Minsk in 1896, deals with the distant past of his adopted country, his picture is among those in the show that engage with, and manage to contest, the nation’s founding myths. Consider the contrast between Kantor’s picture and the nearby work by Doris Lee. Her Thanksgiving (c.1935) is a scene set in a farmhouse kitchen, and, with its aproned matrons, roasting turkey, cute kiddies and playful kitten, makes for as reassuring a picture of plentitude as a hungry man might dream of; it is not, however, great art. But Lee’s inclusion in the show helps convey the range of tasks taken on by Depression-era painters. The previous images of America in art – the frontier, the cloudless sky, basin and range, the noble or dreadful savage – had turned to dust. O Pioneers! gave way to The Grapes of Wrath. With the Great Plains a dustbowl and the traditional trek westward flooded with starving families, there wasn’t much call for landscapes in the grand manner of the Rocky Mountain Sublime.

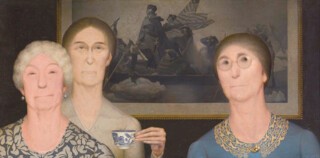

Social satire and protest began to matter: class and race became visible – i.e. permissible – in painting; the past was reinvented and put beside representative objects of the present day. In the course of the 1930s, the nation’s painters showed the streets of Harlem and the factories of Henry Ford; they depicted Midwest diners and Broadway theatres, union leaders and randy sailors, lynch mobs and crews of cotton-pickers; gas stations and cornfields; and, unforgettably, three worthy ladies of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, whom Wood painted in 1932.

The result, Daughters of Revolution, is not a portrait in the familiar sense. It is a vision of the sort that transforms homely familiarity into its unnerving opposite. Backed by a lithograph of Emanuel Leutze’s grandly nationalistic Washington Crossing the Delaware, Wood’s women make their own valiant stand. With willow-pattern cup and handmade lace collar, hair waved, parted and netted, they seem fully equipped to face … what? This is the question posed and deflected by the bland self-satisfaction all three faces express. Wood’s trio are a set of strangely inbred organisms, creatures only able to subsist in dim isolation, far from the light.

Wood made no bones about the fact that in painting this picture, he aimed to distil a social type. Strictly speaking, he told a local reporter, these faces are composites, derived from the photographs that peppered the publications of the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Then as now, the group equated patriotism with privilege, and saw revolution as something that had happened once, long ago, thanks to the efforts of the best families. Wood nicknamed the threesome his ‘tory gals’. The title he gave the work turns on the difference between the radical daughters who might be spawned by ‘the revolution’, and those who believe instead that ‘their’ revolution produced an elite.

Of all the painters in the exhibition, Wood seems most consistently able to animate and, if necessary, reanimate, his nation’s past and present. It is as if he’d devised a way to infuse his subjects with something – call it pictorial aliveness – all their own. Consider the rhythms that impel his treatment of Henry Longfellow’s epic poem of 1860, ‘Paul Revere’s Ride’, which begins:

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

Revere’s nocturnal gallop through the villages around Boston, famously undertaken to spread the news of a planned raid by British soldiers, lasted well into the small hours: hence the darkened landscape in Wood’s picture, which maps Revere’s path as a shadowed ribbon of roadway unfurling through a quiet spring night. Behind the horse and rider, dots of light pierce the depths of the picture’s darkness; ahead, the clapboard houses are still sleeping. The strategic vantage point seems to anticipate the victory to come. Few other painters in the 1930s were able to match this inspired mix of history and legend, or do so much to animate a composition. Against the twisting road, Wood sets the slower curves of stream and river; in contrast to the lollipop trees in the distance is the delicate tracery of those in the foreground, which, as befits an April evening in New England, are just leafing out.

Longfellow’s poem, composed on the eve of the Civil War, shares something of Revere’s minatory purpose. Wood seems ready to trade the poet’s rousing rum-tum-tum for a more melodic refrain. It is only in retrospect, having turned away from the pleasures of Wood’s sleeping landscape, that we grasp how distant Revere’s valour has become. For Wood, past and present both work best when they are treated as myth.

Perhaps this is the reason America After the Fall seems such a timely exhibition. Again and again it confronts us with paintings that struggle with questions of tone, from a time when for many Americans, the country seemed distinctly out of tune. What is a fallen nation? Where is its future? Has the national dream ceded to a dystopian vision? What makes up this new world? Chewing gum and speakeasies, shore leave and lynchings, swing music and roustabouts? What then of farm and factory labour, when livelihoods are lost?

For Wood, such losses divulged a set of subjects he was eager to paint. Take the farmer and his daughter, that dour upright pair whose faces, the artist said, had ‘stretched out long to match the style of their house’. In 1930, the year Wood painted American Gothic, farm foreclosures, like bank failures, were at record levels. What better moment to transform a portrait of a Midwestern couple into an icon of embattled probity? Together they make an anxious stand in front of their clapboard gothicky cottage, defending the lace-curtained windows, the begonias on the porch. All of it is scrupulously rendered, yet the result is pure myth or, better, pure history, for which Wood’s sister and his dentist were enlisted to pose.

Wood was not the only artist of his generation who was able to figure the national ‘fall’. The RA show puts many of them on view. No one should miss the chance to study Charles Sheeler in particular, who in the boom years of the late 1920s found himself working for the Ford Motor Company at their vast River Rouge complex outside Detroit. His American Landscape of 1930 was one result, a picture that fashioned a formal geometry from industrial building types, and in the process managed to transform the stock imagery of ‘energetic labour’ into a world without work. Almost nothing moves in Sheeler’s American vista, just factory smoke, the river’s surface, and a single running worker, who will never reach his goal.

Sheeler, like Wood, was trying to find some means of depicting what had happened, or even was still happening, in an America where without warning, work had ground to a halt. Is that present now safely past? American Landscape, American Gothic, Daughters of Revolution, Haunted House: the story told by these titles no longer seems so securely a thing of the past.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.