‘English Work’, opus anglicanum, was a luxurious kind of embroidery made in England in the 13th and 14th centuries, used to decorate ecclesiastical vestments – copes, chasubles, dalmatics – as well as banners, book bags, seal covers, cushions and other objects. Fabric grounds of linen, wool and silk were covered in figural scenes and rhythmic or sinuous ornament which shimmered with threads of coloured silk, silver and gold, and sometimes even pearls and precious stones. It was produced mainly in London, but there were provincial embroiderers too, at York, Norwich, Colchester, and possibly Exeter, and it could be bought at regional fairs. But its reputation was international. The chronicler Matthew Paris described Pope Innocent IV’s greedy reaction to these sophisticated English products: ‘Truly, England is our garden of delights,’ Innocent is reported to have said, ‘an inexhaustible well from whose plenty many things may be extorted.’ (Paris went on to note that ‘the London merchants who dealt in these things were not displeased, and sold them at whatever price they chose.’)

In many ways opus anglicanum was not very English at all. To the names of the thread-makers and embroiderers Christiana of Enfield, Catherine of Lincoln, Maud of Canterbury, John Machon, Alyse Darcy, Alice Catour and Thomas Bell could be added those of Alexius and Andronicus Effomatus, Greek ‘workers of damask gold’ (drawn gold wire) in London; John of Cologne, a German immigrant working for Edward III in the 1330s; Giles Avenel of Brussels, who made pieces for the Black Prince; and the Fleming Stephen Vyne, whose recommendation from the duc de Berry secured him work with Richard II. (The remarkable number of known names attests to these craftsmen’s prestige, although it’s rare that individual pieces can be attached to a particular maker. The case of an early 14th-century band embroidered with a text from the Litany of the Saints is unusual; on its reverse is an inscription that reads ‘iohnna beverlai monaca me fecit’ – ‘the nun Johanna of Beverley made me’.)

Matching the internationalism of the producers, who were supplied with designs by painters, illuminators, and sometimes by model books, was that of their patrons; the kings and cathedrals of England sought out the famous needlework, but so too did the popes, the College of Cardinals, and the Continental courts. The names given to surviving examples reveal their destinations: there are the Syon, Butler-Bowdon and Steeple Aston copes, and the Chichester-Constable chasuble, but also the Vatican, Pienza, Toledo and Bologna copes, the Ascoli Piceno cope, probably presented as a diplomatic gift by Edward I to Gregory X, or the Madrid cope, referred to in an inventory of 1397 in the Church of Santa María de los Sagrados Corporales near Zaragoza as ‘an excellent cope or pluviale completely worked in gold with various images of silk and with the front orphrey decorated with pearls’.

Above all, what made ‘English Work’ an international, even global affair were the materials it employed. Linen came from France and the Low Countries, silk often from the Near East or China, possibly even the Mongol Empire, and increasingly from elsewhere in Europe. (It wasn’t until the influx of French refugees after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 that the English silk industry really took off in London.) Freshwater seed pearls – like the ones used for the lions’ heads that punctuate the twisting oak branches of the Butler-Bowdon cope – could be found in Scottish mussels, but others came from the Persian Gulf and from the coasts of Sri Lanka and India. In London, specialists like Alice Prince produced gold and silver threads by winding thin strips of metal round a silk core (the name of one of her assistants attests to her occupation: Matilda le Goldsherer). Alice worked for Edward III in the 1330s at a rate of eight pence a day.

At the top of the complex textile trade were the mercers, the merchants who controlled the raw materials. The Guild of Broderers, though not granted a royal charter until the 16th century, grew in strength throughout the 1300s. Already in the 1380s, a group of embroiderers petitioned the king as ‘les Brouderers de la Citye de Londres’. In 1495, perhaps in response to undercutting, the Broderers petitioned to the mayor and aldermen of London that no citizen embroiderer should employ a foreign craftsman, except if granted permission from the company. By the turn of the 16th century, English needlework no longer looked like such a transnational affair.

One of the most beautiful vestments on display in the V&A’s exhibition Opus Anglicanum (until 5 February) is the Clare chasuble, commissioned sometime between 1272 and 1294 by an aristocratic lay patron, Margaret de Clare. Later cut down from its original size to give more freedom to the arms, the chasuble (the priest’s outer garment) is formed of a ground of blue kanzi, a luxurious fabric of silk and cotton imported from Iran. Against this background of precious blue – the earliest known use of kanzi in England – generous, calligraphic tendrils enclose lions and griffins, whose spreading claws rhyme with the taut flourishes of the buds and leaves. Scholars call this kind of ornament ‘inhabited scroll work’. Similar scrolling can be found on medieval English floor tiles, and in the metalwork of the great York Minster cope chest, installed at the exhibition entrance. As with many other patterns of this period (the interlocking stars of the Vatican cope, for instance) it, too, came from the East.

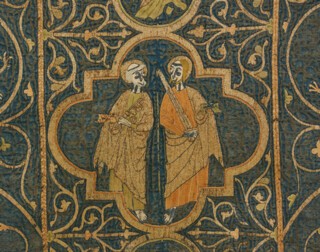

The splendour of such a garment encased the officiating priest in what was understood to be his immortal body. During mass, it was also a moving picture. Along the length of the chasuble’s spine are four figurative scenes contained within pierced or ‘barbed’ quatrefoils. They show the martyrdoms of Saints Stephen, Peter and Paul, the Virgin and Child enthroned, and the Crucifixion. When the priest turned east to celebrate the consecration of the sacrament, and raised his arms aloft with the bread and wine, Christ’s living body and blood were linked to his image hanging on the embroidered Cross below. The dynamic vestment was central to the drama of the liturgy. Cardinal Giacomo Stefaneschi (himself a patron of Giotto and Simone Martini) witnessed a cope in action at Avignon in 1313. During the ceremony, Clement V ‘changed vestments, and put on a very beautiful cope of English embroidery with figural decoration and a mitre embellished with pearls’. It sounds like a scene-change for the climax of a stage play.

The elegant curling forms of the Clare chasuble point back to their Eastern origins, but they also point forward. It’s impossible to look at this fabric without thinking of Morris or Voysey, or even art nouveau. Those drawn-out, tapering lines resemble the handles of a piece of silverwork by Charles Ashbee. Objects like this chasuble were central to the story of the Arts and Crafts movement and of the V&A itself. In the more general context of the Gothic Revival (stimulated by Catholic Emancipation in 1829), medieval embroidery was collected from the inception of the museum; the Clare chasuble was acquired in 1864 along with the Syon Cope. Grace Christie’s groundbreaking book on the subject, English Medieval Embroidery (1938), provided the foundation for the V&A’s survey exhibition of 1963. Installation photographs from that year suggest a space not so different from the clean, clear layout of 2016 – a welcome respite from the multisensory chaos of 1960s counterculture in the exhibition You Say You Want a Revolution? next door.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.