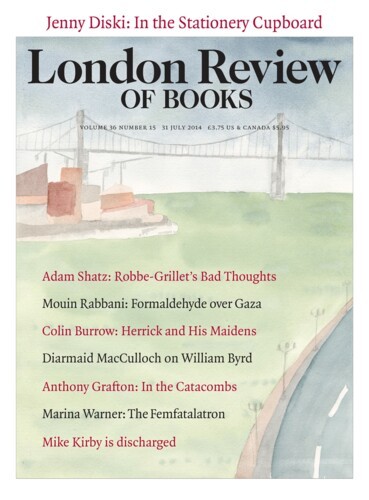

We know a gratifying amount about William Byrd, partly thanks to quite recent archival rediscoveries, and Kerry McCarthy splendidly and concisely presents it all in this intelligent and affectionate biography. Alas, the one thing we don’t have is a contemporary portrait, not even anything as clumsy as the universally recognisable dome-headed icon of Shakespeare: the portrait-image of Byrd adorning CD sleeves and scores is an unimaginative Georgian-Tudor pastiche. That poses a problem to designers of dust-jackets for Byrd biographies. McCarthy or her designer has opted for a picture which, though initially a baffling choice, nails down half his identity very well. It is a pioneering forebear of those group photos taken at the end of G20 summits and the like – world statesmen exhibiting false bonhomie to camera – although the conventions of oil portraiture don’t include the wide smiles of the 21st century, which the deficiencies of Tudor dentistry would also render unwise. The picture shows the English, Spanish and Flemish delegates at one of the most important peace conferences of the Tudor age, which took place a year after Elizabeth I’s death at Somerset House in London. They had succeeded in ending three decades of cold and hot war between Reformed Protestant powers and the Spanish Habsburgs, confirming in the process the independence of the Protestant Northern Netherlands, and offering the possibility that Roman Catholicism might not always be seen as the inevitable enemy of the Elizabethan way of life.

Remarkably, all five of the English politicians portrayed on one side of the Somerset House table in 1604 were linked to William Byrd.1 The most powerful, the great Protestant statesman Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury, was the dedicatee of one of Byrd’s last and most haunting keyboard ensembles of pavan and galliard, so popular that they were still admired and adapted through the centuries when most Tudor music was relegated to the archives.2 Beside him are Thomas Sackville, earl of Dorset, and the earls and cousins Charles and Henry Howard. All three were Byrd’s patrons, and to various degrees shared the shifts and ambiguities of his religious convictions; it was odds-on that all of them would have conformed to a restoration of Catholicism in England if it had happened to take place. The fifth figure, Charles Blount, earl of Devonshire, would have enjoyed the complimentary references to his scandalously flaunted mistress Lady Penelope Rich in several of Byrd’s songs written around this time.

And so Byrd’s public life is refracted through the images of these English noblemen. He was the much honoured and privileged royal servant to Elizabeth and James for more than half a century, called ‘a father of music’ in the records of the Chapel Royal at his death in his eighties; a man of affairs who, when he produced a list of reasons to become proficient in singing, emphasised first its benefits to health and public speaking. To judge from one of his surviving books, Byrd may have been at home in the barbarously archaic Norman-French of the Tudor law courts, which he certainly exploited with enthusiasm in perennial litigation, as any self-respecting Elizabethan gentleman would. It is symbolic of a certain insularity in Byrd that he owned this peculiarly English legal text while his inept word-setting in his one Italian song reveals that he had no idea how that language was spoken. And he never travelled abroad, so never experienced the working-out of the Counter-Reformation in mainland Europe which followed the end of the Council of Trent in 1563, unlike many young Englishmen of restless spirit and Catholic inclinations.

The Somerset House picture is still only half William Byrd. If McCarthy’s publishers had budgeted for a back-cover image, I would have recommended an empty lawn on the fringes of North London: the site of the gargantuan Romanesque abbey church at Waltham Holy Cross, whose admittedly stately parish church abutting on the west end of the lawn is often mistaken by casual visitors for part of that lost building.3 The monastery was closed and stripped in 1540, around the time Byrd was born, Waltham being the last purely monastic house in England to suffer Henry VIII’s dissolutions. So Byrd would never have experienced its echoing acoustic, unlike his collaborator and close friend Thomas Tallis (later godfather to Byrd’s youngest son, Thomas), who lost his job as organist when Waltham Abbey was destroyed, and who thoughtfully squirrelled away a century-old manuscript on music theory from the abbey’s library.

Yet it was Byrd who seemed to mourn that lost world, not Tallis, who had actually been part of it. ‘His nostalgia was that of a young man for something he had never really known,’ McCarthy remarks. It might equally be said that Byrd created an English Catholic musical future which failed to come into existence; English Catholics wouldn’t have the public presence or the resources needed to use his work for another three centuries (and even then not many of them did). Byrd delighted in producing choral settings of the innumerable fragments which make up the ‘Proper’ of the Mass: those sections of text, mostly particles of scripture, which – around the unchanging core sections of the service from Kyrie to Agnus Dei (the ‘Ordinary’) – orchestrate in a literal sense the mood-music through the intricate shifts of the Catholic liturgical year. His two late printed collections entitled Gradualia encompass no fewer than 109 such occasional pieces, mostly no more than two minutes long, but collectively a formidably luxurious provision for a service which throughout his adult lifetime was illegal in England, and for celebrating or even attending which a person might be executed.

Byrd lived through a period of chaos in English church music without parallel in our history; not even the 17th-century civil wars produced such a sequence of rapid reversals of fortune, all the work of four successive Tudor monarchs. The last years of Henry VIII, when Byrd was a child, witnessed a slow leaching of life away from those parts of Catholic devotional practice that the king had allowed to remain after the dissolution of the monasteries. Edward VI presided enthusiastically over a wholesale assault on this Catholic tradition which, if he had not died in his teens, would probably have eliminated all church organs and any liturgical music more elaborate than metrical psalms, together with the cathedrals which had continued to provide shelter for professional church musicians. English religion would have resembled what Reformed Protestant Scotland became in the next few decades. Queen Mary not only restored traditional Catholic liturgy but encouraged new experiments destined to turn into the Counter-Reformation, one tiny symptom of which is a fragment of an Easter Vigil psalm by ‘Byrd’ (then a teenager, if it is our William) which represents an interesting and unusual collaboration with much older composers.

Mary enjoyed even fewer years of power than her half-brother, and the Roman Catholic English establishment died with her. Queen Elizabeth brought back a Reformed Protestantism which in the parliamentary and convocation enactments of 1559-63 suggested a return to the last and most destructive phase of Edward VI’s reign, based on a Prayer Book and theological statements virtually identical to those he had sanctioned in 1552-53. But Elizabeth was not Edward. She had her own rather mysterious religious convictions, which she usually had the sense to keep to herself – the most effective means of getting her own way by stealth. She confounded the expectations of her subjects, Catholic and Protestant, not by the positive legislation of the Elizabethan settlement, but by what did not happen next. Music was one of her great enthusiasms, and her personal religious amenities, provided by the institution of the Chapel Royal, included much elaborate choral music (backed up by pipe-organs) which acted as a protection and example for the surviving greater churches. While parish church choirs faded away unless they knuckled under to the nationwide regime of Geneva psalms, the cathedrals and choral establishments were not drastically modified, let alone unroofed like Waltham Abbey. Cathedrals became a subversion of what was otherwise in essence a fairly typical Reformed Protestant church, providing an example of the ‘beauty of holiness’ which went on to create a second identity for the Church of England that has endured right up to the present day. The C of E has evolved willy-nilly towards a theological schizophrenia, in which self-consciously ‘Catholic’ and ‘Protestant’ identities are paradoxical but indestructible strands of a double helix.

All that was in the future beyond Byrd, but his career remained inseparable from the inbuilt contradictions of the newly established Protestant Church of England. His first major job came in one of the surviving cathedrals. Francis Mallett, then dean of Lincoln, had once been Archbishop Cranmer’s chaplain, but after Protestant waverings became one of Queen Mary’s most stridently Catholic chaplains: his continued tenure at Lincoln under Elizabeth was an example of her inclination to let Catholics keep their place in her church as long as they remained sleeping dogs. When Byrd ran into serious trouble for providing over-elaborate music, his woes would have come from the opposite faction among the cathedral staff, forward Protestants, with Dean Mallett passively fronting their complaints (maybe as a not-so-secret Catholic, he didn’t much care what a schismatic cathedral did with its music). Lincoln more happily provided the young composer with a wife, who became a Catholic recusant (refusing to attend services of the Protestant established church) long before he did. She may have been the source of his lurch away from Protestantism, for his brothers remained conformist despite early careers as choristers at St Paul’s Cathedral.

In 1572 a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal drowned accidentally, and Byrd had his chance to escape the tensions of Lincoln. The Chapel Royal continued to afford him the protection of appreciative monarchs until his death, despite his increasingly salient Catholicism. Here his friendship with Tallis blossomed and produced some vigorous musical entrepreneurship by way of a joint royal patent which they secured for music printing, and which long outlived them. After a shaky start during which the public did not feel much need to buy the musical novelties Byrd and Tallis produced together, the patent became a reliable money-spinner, serving a growing market in which amateur music-making became one of the most respectable as well as enjoyable forms of home entertainment.

Some of this published repertoire is dangerously Catholic, as revealed by even a casual perusal of the collections entitled, with careful neutrality, Cantiones Sacrae, but there was a Protestant etiquette here: musical piety banned in church was considered just about acceptable at home, just as there was a much more generous threshold for sacred domestic art than for religious imagery in Elizabethan church buildings. Much of the content is in penitential mood – McCarthy calls the 1589 Cantiones Sacrae ‘a musical cycle with few rivals for sustained gloominess until the 19th century’ – but we might think of this as the Tudor domestic equivalent of lolling in our living rooms before a nice gory murder story or film noir on the telly. There is no evidence that Byrd acquired a downbeat reputation like that of his younger contemporary John Dowland, who showed at least some measure of humorous self-deprecation in writing an instrumental piece entitled Semper Dowland, semper dolens (‘Dat’s Dowland, always doomy’).4 On the contrary, Byrd seems to have been a welcome dinner guest among the great and the not necessarily good, which must have helped a great deal as he negotiated potentially dangerous confessional shoals over the course of sixty years.

Musicians are in any case inclined to blur ideological boundaries in pursuit of their work, and the 16th-century Reformation was not always as easily pigeonholed as the tidy-minded on both sides would have liked. There is the fascinating case of Infelix ego, Byrd’s sumptuous six-part motet from the Cantiones Sacrae, which sets a century-old deathbed meditation by the Florentine reformer Savonarola. What was the significance of this anguished text? If you didn’t know anything about it, you might use it to stiffen your nerve as a harassed Catholic recusant, yet Thomas Cranmer plagiarised it for his final speech before being burned at the stake by Mary Tudor in 1556. Savonarola’s similar death as a heretic hadn’t stopped his writings becoming firm favourites among ultra-pious pre-Reformation English Catholics. How much would Byrd have known of this twisted history?

In any case, Byrd’s hardening resolve to turn his Catholic convictions towards open recusancy in the 1590s did not end his flow of compositions for the Protestant church. One of the most splendid comes from late in his career, his ‘Great Service’, written either in Elizabeth’s last years or James’s first, and only rediscovered in a Durham Cathedral cupboard in 1922: it provides music for Prayer Book Mattins, Evensong and Holy Communion. In its no-expense-spared use of two choirs of five voices, it was surely intended for the Chapel Royal. Up to the 19th century, Anglican liturgy very sparingly employed music for Communion, and it was Byrd’s Mattins and Evensong settings and a handful of his anthems in English which survived in use (his very cheerful psalm adaptation ‘O Lord make thy servant Elizabeth our Queen to rejoice in thy strength’ has enjoyed a recent revival).5 Yet behind this Protestant repertoire lurked the plainsong of the old Western Church, simpler parts of which were still used in Elizabethan cathedrals to chant Prayer Book words, in a fashion which was clearly so universally understood and practised that no one bothered to leave any description of it. Byrd occasionally let fragments of it protrude more aggressively out of his English music, such as in ‘Teach me, O Lord’.6 This is one of his best-known ‘verse-anthems’, a form he helped to embed in English choral tradition, consisting of an accompanied solo alternating with choral sections. In this example, the choir blatantly sings the ‘Tonus Peregrinus’, a plainsong psalm-tone rather atypical in its peregrine wanderings; Byrd must have especially liked it, since it also appears in one of his still very frequently used Magnificats.

We forget just how separate the two confessional halves of Byrd’s choral repertoire were in his lifetime: not even Queen Elizabeth dared allow the use of Latin in choral pieces in the church’s liturgy. Now, in a more ecumenical age, Byrd’s Latin music is probably more often performed liturgically by Anglicans than Roman Catholics, his mass settings in particular (my own parish church sang one twice last Christmas). At the time, a Catholic composer would have expected to spend most of his liturgical energy on the Ordinary of the Mass: in Counter-Reformation Italy, Palestrina wrote about a hundred such settings. Byrd wrote only three, but what a trio they are: in three, four and five parts, all dating from a few years in the 1590s and straightaway put in print by the composer, with only minimum discretion despite the dangers.7

These are the last major English Catholic Mass settings before the 19th century, yet they are not the end of a tradition, and are startling in their lack of deference to what had gone before. Notably, Byrd sets the Kyrie chorally instead of leaving it as plainsong, for the first time in English liturgical practice.8 Admittedly, choirs who sing his three-part Kyrie are puzzled by its almost apologetic brevity. In reality, Byrd must have intended its three solemn chordal sequences to be alternated with sections of plainsong chant, creating something of a musical bridge to a former age. After that opening element of the Ordinary of the three-part Mass, the gloriously athletic ingenuity of the remaining sections gives the illusion of a much denser texture than we’d expect from three voices, but it is easily sustained by an experienced trio of singers, such as might unobtrusively arrive at a recusant country house for a discreet gathering of the faithful. McCarthy intriguingly points to technical indications in the original published text which suggest that Byrd’s Mass settings could each have been performed non-stop over a sotto voce spoken celebration of a Low Mass, adding solemnity to a sacred occasion which was a brave defiance of Protestant persecution, but which nevertheless needed to be over as quickly as possible.

Byrd’s keyboard music was less ideologically freighted, but it too represents a new era in English composition for organ or virginals. This was not based on technical innovation: for the next two centuries English organ-builders remained resolutely uninterested in the growing variety of sounds their mainland competitors were adding to their instruments, so there is little parallel in Byrd to the French romantic drama of Jean Titelouze’s meditations on plainsong, or the lushly proliferating sound effects with which Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck entertained Dutch music-gadders. Yet Byrd’s keyboard compositions span a sixty-year period that witnessed a transformation in sound-worlds. In the mid-16th century, Thomas Tallis’s longer keyboard compositions were weaving variants around the plainsong theme Felix namque; though intellectually ingenious, they are frankly dull and po-faced, either to play or to listen to. Contrast this with the kaleidoscope of moods in the compositions Byrd, John Bull and Orlando Gibbons shrewdly assembled in 1612 as a commercially saleable wedding present for James I’s daughter Princess Elizabeth, Parthenia, or the Maydenhead of the first musicke that ever was printed for the Virginalls. In the intervening decades the compositional centre of gravity moved from ecclesiastical accompaniment to domestic entertainment. One of the most charming is Byrd’s piece simply called Ut re mi fa sol la, which he evidently wrote to encourage a child starting out on the keyboard. The little fingers pick out a slow high scale up and down, while underneath the tutor (Mr Byrd the father?) plays a steadily more vigorous set of variations, ending with the irresistibly jolly dance rhythms of ‘The Woods So Wild’, repeated enough relentless times to satisfy any six-year-old.

There is a modern parallel to this delight in the musical instruction of children. McCarthy reminds us of Joseph Kerman’s judgment that Byrd was to 16th-century European music what Arnold Schoenberg was in the 20th century, but it is Benjamin Britten who makes for a more interesting comparison. There is that combination of pugnacity (seen in Byrd’s case at Lincoln Cathedral and in his lifetime of litigation) and an extraordinary capacity for deep friendship. Byrd’s career was littered with collaborations with other musicians, and his name is linked with them just as Britten’s is with so many of his contemporaries, artists and performers, way beyond the obvious partner in Aldeburgh. But more than that, both men are fascinating in their insider/outsider or conformist/nonconformist status. For Byrd, there is confessional religion: the contrasting symbolism of the Somerset House group portrait versus the empty lawn of Waltham Abbey Church. For Britten, it was not Catholicism but homosexuality. Through most of Byrd’s adult life in Tudor and early Stuart England, the majority of the population regarded ‘papists’ with a similar mixture of repulsion, fear and secret fascination as prevailed in mid-20th-century Britain towards ‘pansies’: the Elizabethan Catholic minority behaved with that mixture of concealment, equivocation, secret pride and clandestine networking still recognisable to older gay men and lesbians today. Byrd and Britten (who ended up as peer, OM and CH) both enjoyed a charmed existence amid a world of persecution partly thanks to their personal closeness to a Queen Elizabeth. Without the continual moral and social dilemmas both faced, we might not have two such extraordinary and contradictory legacies of musical splendour.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.