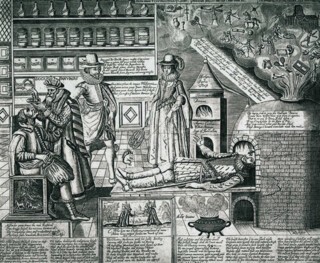

A 17th-century comic print known as The Cure of Folly shows a surgery-cum-alchemical cabinet in which a doctor is treating patients: one is being administered mind-altering drugs; another is being fired and recast in a furnace. This one, a ‘gallant’ in a most elegant get-up, with little pointy moustaches, a lace ruff with multiple layers, soft boots with spurs, and a silk tunic fashionably slashed in both bodice and sleeves, is undergoing the procedure rather in the manner of a modern full body scan. As he lies there ‘the strange chimaera and crotchetts’ which have ‘made him mad’ fly up out of the chimney. The ills expelled include the pleasures and luxuries of the town: dice, hunting, bear-baiting, racquets, duelling, theatre, and the latest excesses of dress. The gallant youth must be purged of his love of puffed shorts, his hosepipe codpiece and flounced silk drawers. The female figure who appears in the rising miasma of his rakish misdeeds is recognisable from the fashion plates in the costume books that Ulinka Rublack vividly explores in Dressing Up. She is a Venetian courtesan, carrying a huge fan of feathers, her pert breasts hoisted above her farthingale to show them off.

Clothes and morals, dress and identity – both national (ethnicity) and social (rank) – spark a series of unfamiliar and arresting questions, which Rublack takes up with obvious pleasure. She likes her subject, finding the vagaries of clothing funny but important, seeming trifles that can reveal serious matters about society and self: ‘mode’ in the sense of custom and process (le mode) is thoroughly entangled with ‘mode’ in the sense of fashion (la mode, a term that entered German, she tells us, in mid-century). Every ribbon signals identity; every padded this or that proclaims status. Her field of inquiry opens on to matters of growing interest, including ‘the things things say’ (to borrow the title of a recent study by Jonathan Lamb), a culture’s techne or craft as an index of its level of civilisation, and the nature of self-consciousness before mirrors were commonly available. She wants to find out, she writes, what it felt like to be someone who wore these clothes. She taps the portraits of her subjects to make them give up information about ordinary daily experience and reads the messages they encode about religious particularism, class expectations and gender propriety. The implications of what she finds can be broadly applied, but the focus of her evidence is more narrow than the subtitle suggests: she draws principally on Nuremberg, Leipzig, Augsburg and other significant towns, like Luther’s Wittenberg. For this reason, prints that circulated throughout Europe tend not to feature in her study, and she fights shy of the propaganda attacks on extravagance and vanity so richly documented in Malcolm Jones’s superb catalogue, The Print in Early Modern England: An Historical Oversight (where The Cure of Folly is reproduced).* The places she studies were rich trading centres, some of them free cities rather than feudal possessions, and their inhabitants used clothing to establish a cohesive sense of decorum and self-esteem.

Rublack wants to place German vernacular art on the Renaissance map, reconfigure notions of Protestant sobriety, and recalibrate the generally accepted view that Germans were uncouth, had little sense of a cohesive national identity and imitated ‘superior’ Italian humanism. In this she is following the lead of the late John Hale, whose last book, The Civilisation of Europe in the Renaissance, let the Danube School of artists, Lucas Cranach and Albrecht Altdorfer, share space with Leonardo et al. Rublack’s quest has taken her to fascinating primary sources in German collections, public and private, some barely known, and her book reproduces many images from these albums, alongside a few surviving items of clothing. Perhaps fantastic raiment, pushing and pulling the body into every shape and contour, is a defining mark of human intelligence and ingenuity – alongside language, writing and laughter. We poor, bare, forked animals, we featherless chickens, as Plato called us, have covered ourselves with multi-coloured hose, beribboned and ruffled partlets, wide-brimmed berets topped with clusters of dyed ostrich plumes and – most startlingly in the days Rublack surveys – ‘peas bodies’, padded belly pillows intended to add imposing bulk to the silhouette. Not to speak of fanciful shoes (the standards of imaginative excess in this area are well maintained today).

Dressing Up takes the argument about material culture and the language of clothes to compelling territory: in her first chapter, for example, Rublack exhibits a truly astonishing album commissioned by a 16th-century accountant in the richissime banking house of Fugger in Augsburg. Matthäus Schwarz was a specialist in double-entry bookkeeping and a fabulous peacock who kept a record of his outfits over a lifetime of an addiction to clothes rivalling any fashionista’s. He commissioned 137 lavish miniatures on parchment and had them bound into a fine volume. In Schwarz’s world immense trouble was taken to get exactly the right look: when Hans Fugger, his employer, set his heart on a coat of lynx fur, he scoured the furriers of Europe for the right pelts from the right part of the back of the animal, regretfully postponing his purchase for another winter when he couldn’t find the deep-pile skins he wanted.

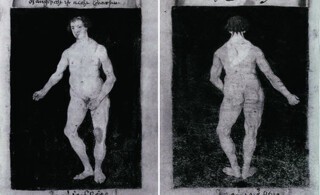

Schwarz’s self-fashioning was dazzlingly comprehensive, as was his desire to provide a complete and accurate record of it: in one image, showing him ‘aged 27 in the year 1524’, he’s a perfect Valentine, a lissom, wasp-waisted figure, his slender legs encased in purple hose, with a floppy Italian red beret on his head, splayed shoes like frogs’ feet (familiar from portraits of the young Henry VIII), and a reticule of green velvet in the shape of a heart hanging from a ribbon at his thigh. Two years later, in the most startling diptych, he stripped off completely and had himself depicted unsparingly, back and front, as if by Lucian Freud. ‘No one had ever done this before,’ Rublack writes. Schwarz’s youth was already receding; he needed to work on his tone. In the last image of all, made when ‘I was 631/2 years and 25 days old,’ he appears dressed for the funeral of his long-time boss; by this time he is a fleshy patriarch with a bushy white beard, swathed in a mantle of the deepest sable, an allegory of Winter.

This costume book, kept in a small museum in Brunswick, the Herzog Anton Ulrich, has elements of another popular print series: Schwarz’s poses might seem to be setting out the Ages of Man. Although the album is the result of an individual’s unprecedented interest in the phases of his own life, neither he nor the artists he commissioned try to explore his character or feelings. It’s his dress that is being chronicled: he isn’t interested in showing how his face changed as he grew older, though with a proper dandyish sense of the figure he cut, he grieved at his increasing girth.

Neither Schwarz’s Book of Clothes nor the other costume studies Rublack discusses is concerned with their subjects’ interior life; they are close to those paper doll cut-out books in which you can hang different outfits, and thus identities, on, say, Joan of Arc (her shepherdess costume, her armour, her rags and shackles going to the stake). Matthäus Schwarz can almost be seen as a precursor of the performance artist: Claude Cahun trying out different personae in the mirror of her camera – now a dejected Pierrot, now a sulky schoolboy, now Helen of Troy – or the mistress of transformation, Cindy Sherman, who showed that a kind of visual karaoke can be performed on the self, that it’s possible to become almost anyone you fancy by mutations of comportment, dress and coiffure. But Rublack’s prize evidence long predates these now familiar ideas of the labile self.

Schwarz’s album illuminates the history of self-fashioning that leads up to Facebook, but it doesn’t form part of the story that Joseph Leo Koerner tells in his tremendous analysis, The Moment of Self-Portraiture in German Renaissance Art (1993). Schwarz’s Book of Clothes isn’t mentioned there, and this makes Rublack’s account all the more important. Like Polonius, who sends Laertes off to Paris with a warning to watch what he wears, ‘for the apparel oft proclaims the man’, Rublack knows that clothes can be seen as a lingua franca, even if the dialects differed from place to place, a language necessary for announcing a public identity and establishing social bonds. Clothes spoke of a person’s character and status, and even the features of a face and the look and gestures of the hands could be groomed to continue that work of self-definition. ‘Everyone’s way is made known through clothing,’ wrote Hans Weigel, the compiler of a huge and comprehensive Book of Costumes in 1577.

The Benedictine monk and poet Dom Sylvester Houédard, visiting the Vatican in the 1960s, came across some nuns at their ironing-boards: they were the pope’s wardrobe mistresses, and their job was to goffer the papal surplices. The pope still has special silk slippers made for him, I think, red ballerinas, and his pallium is woven by nuns from the first shearings of newborn lambs that were dedicated to St Agnes on her feast day, 21 January, in her church in Rome, Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura. Does this ritual still happen? And does Benedict XVI go about in red slippers?

The pope’s trumperies were the target of ferocious satires issued by the Lutherans, whose voices are often raised in this book, but Rublack argues that they were railing at Old Luxury, carefully distinguished from New Luxury, which allowed Luther and many of his fellow churchmen to keep lavish households, stock splendid wardrobes and curl their grown-out tonsures and luxuriant new beards. Rags and slovenliness were ungodly, a poor thanks to the Almighty for his beautiful creation. Cranach, Luther’s friend and portraitist, captures the glorious display of Protestant New Luxury again and again; when we imagine the Reformers we should think of them in sumptuous scarlet and brilliant yellow, not in funereal black, as we do only because of the Puritans of England and New England.

In Germany sumptuary laws were devised to constrain people to behave with decorum and according to their rank. But the laws were always shifting. In Leipzig, for example, where the annual trade fair drew visitors from all over the world and brought new looks from Paris and Florence and Turkey and India, there were strict regulations about ribbons and lace and silk, and who could wear an artificial braid in their hair or gold jewellery or ‘expensive belts with silver decorations’. In 1530, the Imperial Police Ordinance relaxed, and unmarried peasants were allowed to tie up their hair in a silk band (as their betters had been doing). Velvet remained forbidden to many classes, however, and Rublack quotes from a rare cache of letters between a travelling merchant husband and his wife in Nuremberg that illustrates the anxiety all these restrictions caused. Magdalena Behaim frets because her husband has spent too much on a bolt of ‘desired, red crimson smooth velvet’, and tells him that they must keep the expense of it secret and never speak of it. Although she doesn’t say as much, she communicates the same worry about reaching above one’s station and being thereby exposed to ridicule that Jane Austen and Edith Wharton would explore in their female characters. In Leipzig the sumptuary legislators seem to have given up, realising that the law could never catch up with the fashion: ‘what people wear changes almost every year among the German Nation, and from one to the other,’ a town councillor sighed, sounding like a headteacher assailed by yet another fad for knotting your tie this way or that or customising your blazer.

Styles travelled on the same paths as other forms of knowledge: like the new tourists setting off to see the world beyond their native city walls, soldiers, merchants and craftworkers were taking the place of pilgrims and crusaders. Ambassadors travelled with artists and chroniclers to report on the society and culture of foreign lands. Fashion and printing are intertwined, and the costume books Rublack reproduces were often copied and disseminated in different media. As Jones discusses more fully, motifs were reproduced on paper, tiles, embroideries, biscuit tins, dinner plates. A style could carry a cluster of meanings, signalling wealth, availability, citizenship, experience, occupation, age; but when a style went out of style, as it inevitably did, these meanings changed – the subject then looked ridiculous. A cruel fate, terribly caught in the cozening of Malvolio in Twelfth Night.

In terms of fashion, Rublack’s period stretches from the fantastical striped uniforms, codpieces, and fluttering galloons and feathers of the Landsquenets, or halberdiers, mercenary soldiers of the Habsburg Empire who until the end of the Thirty Years War embodied an ideal of ferocious Teutonic virility, to the less swaggering and ostentatious fashions of the mid-century, when a more subtle and softer ornamental aesthetic, inspired by fabric from the Ottoman Empire and India, brought sprigged cotton, richly woven paisley and silk damask to the wardrobes of those aspiring members of the urban population who could afford the latest Oriental allure – or its imitations. The girl with the pearl earring, Rublack thinks, posed for Vermeer wearing a painted glass bead in her ear.

An eirenic impulse carries this study, as Rublack seeks to undo many assumptions about the past and its ills and its prejudices: in the chapter ‘Looking at Others’ she finds open-minded ‘moral geographies’ in the fashion for costume books from around the world, compiled from travellers’ tales. These early ethnographers, she writes, don’t sneer but show tolerant curiosity about different cultures. One of her major finds, a huge compendium of costumes put together between 1560 and 1580 by another bookkeeper, a Nuremberg official called Sigmund Heldt, gives congenial evidence of humour, egalitarianism and a deep sympathy with all conditions and occupations. It helps that the Germans weren’t taking possession of the countries they visited, trading in slaves, or building an empire. The 16th-century illustrator Christoph Weiditz’s watercolour of Sold Moors shipping water on the docks in Barcelona shows the slaves’ fetters lined with cloths to try to stop chafing. Elizabeth McGrath discusses at far greater depth in From Renaissance Trophy to Abolitionist Emblem, her forthcoming book on depictions of slaves, how this article of dress (so to speak) recurs often invisibly, a symbol of slavery itself. Although Rublack reproduces the image in full colour, she somehow misses the point when she writes that Weiditz ‘was … interested in how different types of labour were performed and, in this case, how the use of labour through the ownership of a person was politically embedded.’

In her chapter on ‘Nationhood’, the inhabitants of northern countries – Lapps and Irish, for example – come in for special praise ‘as the new, hardy warrior-race’. At times, as when she talks about the cult of Muth, German liveliness or ‘spirit’, one can feel the wind blowing from the future, but Rublack doesn’t face it full on. The anti-semitism that stirs rather too frequently in stories about the rag trade also doesn’t get discussed as unflinchingly as I would have liked. She prefers to concentrate on the positive sides of her subject, and there she has found much to enjoy, including the vivid testimony of working women. A gravedigger’s daughter, Anna Riek, from the small town of Laichingen, married a day-labourer and brought as her trousseau three scarlet laced bodices, a quantity of silk kerchiefs and a cap à la Parisienne. One of her bodices was striped in the French tricolore. The year of her marriage was 1798, and clothes, more than ever, signalled political and social allegiance.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.