A couple of markers may help. We are all situated somewhere, even if we see ourselves as cosmopolitans emancipated from mere biography. I was a beneficiary of the old idealistic British system, a grammar-school boy who went to Cambridge in the 1950s when not too many people were so lucky. If we can’t afford such a system any longer because we wish to make a good education available to many more people – if that is our real reason and our real intention – then we have to think of proper new ways of funding it.

But we can also remember the values of such a system, whatever the costs. My parents had to be persuaded to let me stay at school after I was 16, but they were fairly easily persuaded, and the whole larger culture helped to persuade them. Higher education was a good thing because it was free, and it was free because it was a good thing. It was what we now call ‘cultural capital’ – and far more closely connected to culture than to capital. That sense of education as a ‘public good’ is itself of inestimable value and makes everything else possible: music college as well as agricultural college, free inquiry, disinterested curiosity, engineering school, degrees in dead languages. We can gloss this value in detail, and we should; but we can’t and shouldn’t turn it into value for money, or confuse value with extensive use.

But what if we are not given a chance to provide this gloss, or turn out not to be up to providing it? Second flashback, to the bad old days this time. I returned to England at the time of the Malvinas War, sometimes known as the Falklands War, and taught at Exeter University until 1995. When asked about this period, I usually say I found the battles on behalf of the university (the department, the school, the discipline, our younger colleagues’ jobs) very hard work but exhilarating: there was something to fight about. But it was no fun losing all of the battles, and I am still trying to work out what it means that we should so thoroughly have lost all of them. What can we do about it?

Let me put the matter as starkly as I can. If we can’t speak the language of our enemies, not only will they not listen to us – they might not listen to us anyway – but they can’t. We need to be saying things they could hear if they would listen. ‘They’, by the way, includes all kinds of people within universities as well as outside them. But what if we can’t speak that language without losing the battle? What if the very language wins the battle by definition? What if we can’t speak of cost-effectiveness because we don’t understand either cost or effect in the way our enemies do? How do we make astrophysics sound useful without turning it into science fiction? Just what sort of transferable skills do we pick up from Greek metrics? I think of a line from Mallarmé: what’s the good of trafficking in what should not be sold, especially when it doesn’t sell? A thought triggered by David Willetts’s amiable description of the publications a distinguished scholar might bring to the RAE as ‘a good back catalogue’. Austin and Wittgenstein had plenty of thoughts, and a huge influence on philosophy, but at the time of their death almost no catalogue, back or front.

This is not a narrow question of terminology – although I’m not sure questions of terminology are ever all that narrow. During the Thatcher years, as during the Reagan years in America, a strong assumption arose that the quarrel was not between right and left or between different opinions and positions, but between those who knew what reality was and those who didn’t. If you didn’t know what reality was – that is, if you disagreed with those who were sure they knew and had the power to implement their views – it didn’t matter whether you were right or wrong, since you were irrelevant anyway. And reality was … whatever you could get a largish number of conservatives (small c) to take seriously. This move was particularly devastating in America, where liberals shared with conservatives a consensus against extremes, and on the whole still do. Left-wing liberals were a special problem, because they genuinely believed they had gone as far left as anyone could reasonably go. The current array of protests in both Britain and America is an encouraging sign in this respect: dissent may be rational again, rather than someone else’s insanity.

So when what is real, in relation to university education, is student demand and jobs in the future – a pair of premises about as fictional as you can get – what are we to say in favour of the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake? Especially if the very notion of doing anything for its own sake has more or less vanished from the national landscape? What can we say that is not vague, without falling into the market trap?

Here are two modes of an answer, which we may need to deploy both together and separately, as strategic need arises. First, the quest for knowledge needs no justification except the energy and enthusiasm, the passion it inspires, and a society that doesn’t encourage such quests for their own sake has already started to impoverish itself in ways it may not be able to see. Nietzsche once defined human beings as animals who had invented knowledge – well, literally they had invented knowing, erkennen, ‘getting to know things’, and recognising them. If we can’t care about knowledge enough to let others look for it even if we don’t want to, we shall be the less human for it, or human beings of a lesser kind. And here even this first answer based on the virtue of disinterested inquiry begins to slide towards the practical, since a society that does not value knowledge in this way will soon be outpaced in all kinds of areas by societies that do.

Second mode of answer. If we live in a secular society, and do not have a special insight into God’s plans for us, we don’t know what knowledge will be useful to us in the future. And more important, we can’t know what knowledge we may find at the end of an apparently pointless or even crazed inquiry. Many of our most useful inventions began in the realms of purest theory. This is not to be mindlessly optimistic. The motto from Marie Curie hanging up outside the British Library is quite wrong. ‘Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood.’ We may well fear many things, and we should, and some things we shall fear because we understand them. But this is not a reason for not wanting to understand them. We can deal well or badly with the knowledge when we have it; but we can hardly want to shelter in our ignorance, it isn’t any safer there.

If you want it you’ll pay for it and if you won’t pay for it you can’t have it is a perfectly reasonable principle if you’re running a small shop, but it won’t even work for a business, once it reaches any size – you’ll lose out to the competition, which isn’t watching the pennies so closely. Where is the invention, the new technology, all the wrong roads in research that allowed a few right roads to be found? In the part of New Jersey where I live the object of much local nostalgia is not any university or establishment of learning, public or private, but the old Bell Laboratories, fondly remembered as a place where people pursued research for its own sake, with only a secondary thought of profit for the company. I have never entirely believed that these laboratories were this legendary place, but I’m not sure my wary scepticism should survive my just acquired knowledge that the place has been the home of seven Nobel Prizes. In any event, such a set-up is clearly possible, or was possible. And can cease to be possible, as is shown by the record of the current owner of the labs, the French company Alcatel-Lucent.

And this possibility leads me to the distinction between business and business-speak, and more broadly between the working corporate world and the world of business and management schools. We are being asked to imagine our universities not as real businesses, but as dream businesses of the kind thought up by people who work only with models and yesterday’s quality assessments. Of course, the distinction is not absolute. There are businessmen who really believe in the free market – until it stops believing in them. Thatcher believed in the market until the Americans stopped buying British aeroplanes. Then she believed in the special relationship. Business and management schools no doubt do teach practices that are (sometimes) actually practised. But my experience of working with the Leverhulme Trust, for example, suggests strongly that many leading executives, like the rest of us, are interested in quality for money, which is quite different from value for money, and even interested in qualities that don’t immediately have to do with money at all. Their question would be, about a Sanskrit scholar, say, ‘How good is she?’ not: ‘Who cares about Sanskrit and why should we pay for it?’ This is in contrast to Thatcher’s response to an undergraduate at Oxford who told her she was reading history. Thatcher is supposed to have said: ‘What a luxury.’ Those who think the supposedly unpractical sides of higher education are a luxury for which the state has no responsibility are right in a quite wretched way. They won’t have to pay for them. But their children will, and so will ours – and not with money.

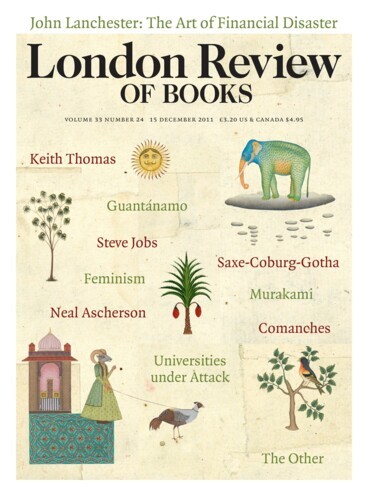

Keith Thomas and Michael Wood spoke at ‘Universities under Attack’, a conference sponsored by the ‘London Review’, the ‘New York Review’ and Fritt Ord held on 26 November at King’s College London.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.