Eight years, billions of dollars and thousands of dead bodies into the ‘global war on terror’ – sorry, Mr President, the ‘overseas contingency operation’ – and we still don’t have an answer to one of the fundamental questions: where is Osama bin Laden? Other, of course, than skulking invulnerably in the darker corners of the Western public imagination, where he is plotting to steal nuclear warheads, cooking up GM anthrax, reading (or misreading) the Quran, and making interminable speeches to his acolytes, possibly punctuated by bursts of insane laughter. It’s unlikely that the forthcoming book by bin Laden’s first wife and fourth son, which emphasises his love of gardening and the World Service, will do much to change that.* Even Blofeld had a cat.

In fact bin Laden hasn’t needed to do anything much lately, because the US government has been doing such a grand job on his behalf, not least by spending billions of dollars breeding killer bugs in laboratories all over the US, ripe for the stealing should bin Laden ever feel moved to launch a biological attack on the Great Satan.

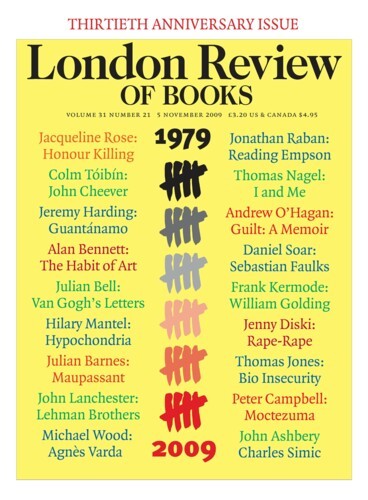

In Breeding Bio Insecurity: How US Biodefence Is Exporting Fear, Globalising Risk and Making Us All Less Secure (Chicago, £19), Lynn Klotz and Edward Sylvester make a compelling case for a radical and immediate change in America’s biosecurity policy. Since 9/11, according to the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, the US government has spent $50 billion on its biodefence programme: Klotz and Sylvester estimate that about a quarter of that has gone on research and development into ‘bioweapons countermeasures like antibiotics, antivirals, antidotes and vaccines … Testing them clearly requires ready availability of the bioweapons agents themselves.’ This activity arguably contravenes the Biological Weapons Convention, which Nixon signed in 1972, since signatories to the BWC undertake ‘never in any circumstances to develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain … microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes.’

There’s the loophole: it’s biodefence. They need all that anthrax, smallpox, plague, ricin, botulinum and ebola to enable them to work out how to protect themselves from an attack. That’s what both sides said during the Cold War, too – not that either side believed the other. The extreme secrecy surrounding biodefence in the US, Klotz and Sylvester say, only encourages nations that fear they may be potential targets of America’s ‘biodefence programme’ to embark on ‘biodefence programmes’ of their own. And so it escalates.

Klotz and Sylvester argue that the biological threat from terrorists has been grossly exaggerated: growing, storing, weaponising and delivering large quantities of lethal viruses or bacteria isn’t at all easy – not to mention quite likely to kill anyone trying to do it under less than optimum laboratory conditions – and way beyond the capabilities of most nation-states, let alone a terrorist organisation. The extremely well-funded Aum Shinrikyo cult in Japan resorted to sarin gas in their attempt to bring about biological or chemical Armageddon only after their experiments with anthrax, botulin, cholera and ebola came to nothing. Less than a month after the sarin attack on the Tokyo subway, which killed 12, Timothy McVeigh murdered 168 people in Oklahoma City ‘with a homemade bomb made from nothing but fertiliser and heating fuel’.

The extreme unlikeliness of a large-scale biological terrorist attack hasn’t stopped the flood of funding to biodefence research projects, however, or the consequent goldrush among researchers. As Klotz and Sylvester report, ‘the number of people working in biodefence has increased perhaps twentyfold in the past decade,’ and there are now ‘219 labs registering with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to study anthrax alone’. Klotz and Sylvester call this ‘massive overkill’. Al-Qaida didn’t need to build the planes they flew into the World Trade Center: if they wish ‘to carry out a bioweapons attack in the US’, Richard Ebright, a microbiologist at Rutgers has said, ‘their simplest means of acquiring access to the materials and the knowledge would be to send individuals to train within programmes involved in biodefence research.’ Background checks are carried out on would-be researchers, obviously, but according to Ebright, ‘Mohammed Atta would have passed those tests without difficulty.’ David Ozonoff of Boston University doesn’t see why they’d bother: ‘Bioterrorism to me is analogous to an autoimmune disease. We did it to the Soviet Union, we bankrupted them in the arms race. Now, al-Qaida is going to bankrupt us on the biodefence stuff.’

Even if the system isn’t infiltrated by al-Qaida, one disease or another could always escape by accident. Klotz and Sylvester document case after case: a lab worker at Texas A&M University getting infected with brucellosis, calling in sick and not being diagnosed for weeks; mice with plague disappearing from a lab in Newark; researchers in Maryland sending researchers in California supposedly dead anthrax bacteria that turned out to be live after all. Then there are the anthrax-in-the-mail attacks of October 2001. It still isn’t known who sent the letters out; the only certain fact is that the anthrax came from a US government lab. The biodefence budget would be better spent, Klotz and Sylvester argue, preparing for more likely and more deadly epidemics: bird flu, for example.

They’re upbeat about the prospects for a more rational biodefence programme under Obama. Their determination to be as positive and patriotic as possible has some weird side effects, though, such as their claim that the US has only recently risked losing the moral high ground so far as the use of unconventional weapons is concerned. Even if you discount the napalm and Agent Orange they dumped on Vietnam, it’s hard to square the claim with the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Klotz and Sylvester also get carried away by some Cold War paranoia of their own, when they talk about ‘the scariest weapons of all: mind-control agents’. It’s not entirely clear what they mean by these: one of their examples is apartheid South Africa’s research into the use of MDMA for crowd control – surely a contender for the most benign thing the regime ever did. Ecstasy or smallpox: I know which I’d rather be attacked with. Bring on the ‘mind control’, please.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.