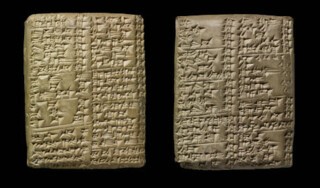

Held in the hand, a typical cuneiform tablet is about the same weight and shape as an early mobile phone. Hold it as though you were going to text someone and you hold it the way the scribe did; a proverb had it that ‘a good scribe follows the mouth.’ Motions of the stylus made the tiny triangular indentations of cuneiform characters in the clay. The actions would have been much quicker and more precise, but otherwise rather like the pecks you make at a phone keypad.

Some tablets are of course larger. Gilgamesh, thousands of words long, is an epic in 12 tablets more than a foot high, and inscriptions carved in rock are more expansive still. But it is the small tablets with tiny writing that are the most tantalising objects in Babylon, Myth and Reality (at the British Museum until 15 March). Can one, through them, get beyond archaeological evidence and inference, bypass the fevered imagination of William Blake’s and John Martin’s Bible illustrations and hear the voice of a Mesopotamian Pepys?

Well, not exactly, but the range and character of what is written down give some idea of the texture of everyday life in Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon. The majority of tablets may be the equivalent of office files – letters, legal documents, contracts, mortgages, lists of goods – but there are also messages addressed to the gods, some of them expressing indignance that good behaviour has not been rewarded. Astronomical observations are detailed and medical texts full of diagnostic descriptions. There are records of refurbishments: the kings, who had responsibility not just for religious ceremonies but for the maintenance of temple structures, celebrated their building works.

Eventually walls crumbled, but the clay survived. Bricks were recycled: archaeologists studying the ruins of Babylon sometimes found them, stamped with Nebuchadnezzar’s name, built into the walls of the houses they were staying in. Work began on the decipherment of Babylonian cuneiform – Babylonian writings were the concern of the first wave of serious archaeologists – after an inscription, engraved for the Persian king Darius high on a rock-face in three different scripts, was transcribed (with much difficulty and danger) by Henry Rawlinson in 1836. By 1850 translation was possible; tablets, seals, inscriptions, whole or fragmentary, were worked on. Cuneiform tablets turned up in remarkable numbers and decipherment of a huge corpus still goes on (the British Museum alone holds 130,000 or so items). The wedge-shaped marks that make up the symbols – some represent syllables, others stand for whole words – are smaller and neater than illustrations lead one to expect. The nearest equivalent in print of these dense rows and columns are the pages of small-format two-column Bibles, printed in type designed to get as many words as possible on the page. Storing information on comparatively bulky tablets encouraged neat writing. On some of them the writing is so tiny that the scribe must have either been severely myopic or showing off.

This exhibition, more than most, is about words. One of three (it follows related Babylon exhibitions in Berlin and Paris), it concentrates on what were, in biblical terms, the last days of the city: the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 BC). Babylon was, even then, ancient; it had been prominent since about 2000 BC, and when the Persians took it in 539 BC, peaceably by their own account, that was not the end of the story. But, while the biblical destruction of Babylon may owe more to the need for a dramatically satisfying punishment for the sack of Jerusalem than to fact, the fortifications, palaces, temples and houses did gradually crumble and fall. Nineteenth-century surveys and excavations identified buildings and city walls and plausibly matched them to descriptions in the writings of Greek travellers and historians, giving Christians and Jews sure knowledge of the very place where Daniel was put among the lions and the Burning Fiery Furnace stood.

In the ‘myth’ part of the exhibition – paintings, prints and manuscript illustrations largely based on the Bible – you see the fall of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar in his madness, the Tower of Babel, the Fiery Furnace, the sack of Jerusalem, the Jews in exile by the waters of Babylon, and Daniel in the lions’ den; all these in circumstantial, if anachronistic detail. In the ‘real’ part you see excavated artefacts, plans and reconstructions: in particular those based on expert work done in the modern manner in the years up to 1917, before the arrival of British troops, by German archaeologists led by Robert Koldewey. The perspective drawings suggest something closer to a modern town planner’s ideas than to the crowded souks and tenements that one imagines, on the evidence of old Istanbul or Fez. But all ages, whatever their evidence, manage to give reconstructions a taste of their own time. The archaeological detail in Edwin Long’s The Babylonian Marriage Market (1875) may be scrupulous, but the girls sitting along the front could be wallflowers at a ball.

Unbaked clay brick, not the most prepossessing of materials, is thrilling stuff when it is shown to be evidence that Bible histories are not just myths, and despite a shortage of worked stone and grave goods, Babylon became an important site. German excavations unearthed enough fragments of the glazed reliefs that decorated the side of the Processional Way and the Ishtar Gate for a reconstruction to be set up in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin. The exhibition includes lions and a dragon from this frieze. Skill in distinguishing mud brick from mud resulted in surveys that on the whole confirmed what classical sources said about the scale of the city (in Babylon it was no good looking for stone footings to map: there were none), and if the snarling, repetitive lions and the high, square-towered gateway are impressive in an unappealingly imperial/totalitarian way that may have something to do with the date and provenance of these German reconstructions.

Even accurate reconstructions are dull beside Bruegel’s imagined Tower of Babel and an ancient bearded god in clay is less terrifying than Blake’s watercolour of a mad, long-clawed Nebuchadnezzar, but paintings and engravings of an imagined Babylon in the exhibition are a mixed lot; some have to stand in for better things illustrated only in the catalogue (for example, lesser Flemish versions of his Tower for Bruegel’s own and Briton Rivière’s picture of Daniel staring down a lion for the restless pride painted by Rubens). Babylon’s reputation as sin city became a licence to take things way over the top. John Martin’s Belshazzar’s Feast is both the English late Romantic imagination at full stretch and a link to Hollywood, where that style found its true home: Martin’s Belshazzar was one source for the vast sets built for D.W. Griffith’s 1916 film Intolerance. In the Book of Revelation the Babylon of the Old Testament prophets is an abstract representation of the evils of luxury and indulgence, personified in the Whore of Babylon. As the years passed, artists used her to refine their visions of a woman flaunting sexual power. One first sees her demurely combing her hair in a 14th-century tapestry. In Dürer’s woodcut she rides her seven-headed beast, slim, over-dressed, quite pretty; she has long ringlets and, in her face, a hint of anxiety. Blake puts flesh on her, and has her bare-breasted, her features handsome and heavy. Several of the beast’s seven heads seem to look back at her disapprovingly.

The exhibition ends with pictures and texts about the damage done to Babylon’s remains, first under Saddam Hussein, when archaeological reconstruction and palace building jazzed up or covered over ancient ruins, and then, in 2003-4, when the heavy vehicles, fuel dumps and defence works of a US military camp cut through, crushed or contaminated significant archaeological deposits. These are in no sense among the worst things Saddam did or the Coalition has done, but they were among the most avoidable and thus least excusable.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.