Welcome. Ahaa, or should I say Yee-haa!, because I, Alan Partridge, am broadcasting live from Las Vegas, US of A, stateside. I promise you tonight we’ll have a real half-pound cheeseburger of a show for you. And it’s a cheeseburger that contains lots of meaty chat, a salad of wit and a flap of amusing cheese.

Knowing Me, Knowing You: Radio Show 3

One of Alan Partridge’s trademark mannerisms was to overextend his metaphors, stretching them to their elastic limit and beyond until they snapped and he was left with a useless, sagging coil of words, a vehicle wholly detached from its tenor. And that appears to be what’s happened here: the cheese in his analogical burger stands only for itself. But then, Knowing Me, Knowing You was – knowingly, amusingly – a very cheesy show. ‘Cheese’ is a loaded symbol: big cheese, hard cheese, the moon is made of green cheese. And there’s something innately funny about the word ‘cheese’, especially if you say it often enough. I don’t know if it sits on an equivalent shelf of the cultural larder in the Netherlands – do Dutch photographers ask their subjects to say ‘kaas’? – but suspect it might, if only on the basis of Willem Elsschot’s comic masterpiece, Kaas, now available for the first time in English, in a translation by Paul Vincent (Granta, £10).

Willem Elsschot was the pseudonym of Alfons De Ridder (1882-1960), an advertising executive who wrote novels in his spare time, ‘unbeknownst to his family’. Kaas was written in the space of a fortnight (it’s very short, certainly less than 30,000 words) in 1933, and published the same year. The narrator, Frans Laarmans, is a middle-aged clerk at the General Marine and Shipbuilding Company in Antwerp. At his mother’s funeral, he meets Alfred Van Schoonbeke, a lawyer and a friend and patient of his brother (12 years older and a doctor), who invites him to his house. ‘He’s got bags of money, and all of his friends have money too . . . Every member of the group has at least one car, except for Mr Van Schoonbeke, my brother and me. But Mr Van Schoonbeke could afford a car if he wanted.’ Laarmans feels cowed in their company, and they tend just to ignore him. But nonetheless he keeps going to the Wednesday-evening gatherings. Eventually Van Schoonbeke asks Laarmans if he would like to be the Belgian representative of a large Dutch firm. ‘I asked him what kind of business his Dutch friends were in. “Cheese,” said my friend. “And there’s always a market for that, since people have to eat.”’ So Laarmans takes three months off work at the shipyard on grounds of nervous illness (he gets a phoney sicknote from his brother) and signs a contract with the Dutch cheese company. His wife has her doubts about the project, which only increase when she reads the unfavourable terms of the contract. In due course, 20 tonnes of Edam is delivered to Antwerp. But Laarmans is so busy being a businessman – setting up an office in his house, buying a desk and a typewriter, deciding on a name for his enterprise, getting headed notepaper printed, enjoying his new status among Van Schoonbeke’s friends – that he never gets round to selling any of the cheese. The problem is compounded by his shyness, his fear of being spotted by a colleague or superior from the shipyard, his total lack of experience, and the fact that he really doesn’t like cheese. Looking at a window display in a cheese shop, he sees ‘huge Gruyères as big as millstones’:

on top of them were Cheshires, Goudas, Edams and numerous varieties of cheese that were entirely unknown to me, some of the largest with bellies slit open and innards exposed. The Roqueforts and Gorgonzolas lewdly flaunted their mould, and a squadron of Camemberts let their pus ooze out freely. An odour of decay wafted from the shop.

The book jacket describes Cheese as ‘a delightful period piece’. (The period details are not always delightful: in a desperate attempt to shift the cheese, Laarmans advertises for sub-agents to sell it for him; the response is huge, and an army of the hungry and unemployed traipses through his office – he hires some and takes pity on others, giving away free cheese and even a pair of shoes. The bulk of the merchandise stays in the warehouse.) But it’s also as ‘relevant’ now as it ever was, not to the modern cheese trade,* but to our ‘age of dot.com failures’. And let’s not forget Enron.

Many years after it was published, Elsschot ghost-wrote an essay on Kaas for his grandson, who was studying the book at school. In it, Vincent tells us, he suggested that the ‘malodorous cheese was a metaphor in the novel for the distasteful advertising business in which both the author and (in other books) his character Laarmans are involved.’ In 1991, Guido Lauwaert proposed an alternative reading: the unsold Edam calls to mind the remaindered copies of Elsschot’s previous, unsuccessful novel, Soft Soap. But it’s always possible, of course, that the cheese stands only for itself.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

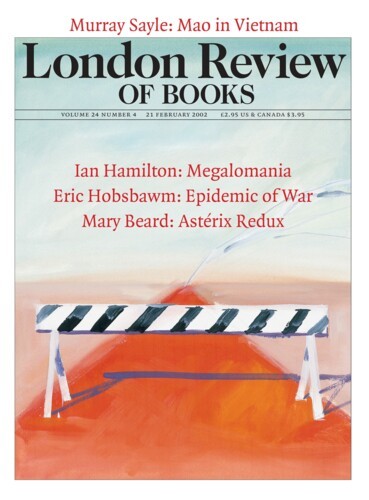

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.