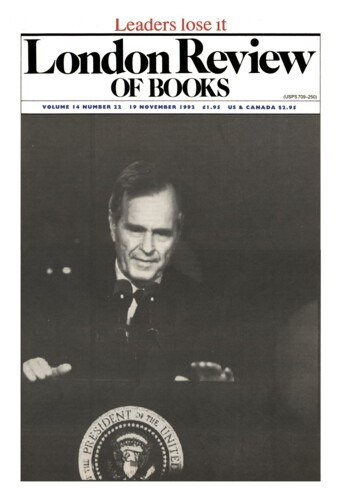

When a Government loses the confidence of its own nominal supporters it is plainly in a bad way. There is a good deal of difference, however, between a chronic malady and a terminal collapse. The Maastricht vote was not the first crisis the Major Government has faced since its unnervingly recent electoral victory. Nor is it likely to be the last. But though these are disturbing symptoms, there are good reasons why they should be seen as debilitating rather than fatal, presaging Major’s decline rather than his fall.

At the time of the Conservative Party Conference, Douglas Hurd warned his party to take heed of the terrible historical precedents of 1846 and 1903 – the two great splits in the Party’s history. From a Conservative point of view this was a pertinent message to deliver, the right thing to say to his audience. It is understandable that at Brighton Hurd did not refer the loyalists (or disloyalists) to the equally notable split in their ranks in 1940, which gave Churchill his chance to put country before party. From a non-Conservative point of view, however, there are different lessons to be drawn, not only from these crises but also from the party splits suffered by the Liberals in 1886 and 1916, and by Labour in 1931.

What happened in 1846 was that Sir Robert Peel’s government failed to carry its own backbenchers with it over the repeal of the Corn Laws. Though the Tory MPs who voted for protection were a majority in the Party, the Free Traders had a clear majority in the House of Commons as a whole, since the Peelites were supported by the Whigs. Indeed, the subsequent formation of the Liberal Party, though it took twenty years of faltering manoeuvres to accomplish, entailed a Parliamentary union between Peelites like Gladstone and Whigs like Lord John Russell. The Gladstonian Liberal Party, which was to dominate Victorian politics, was conceived in the Ayes lobby that night in 1846: it was their baby.

When the baby grew up, it duly encountered its own midlife crisis. In 1886 it was the Liberal Party which split over Irish Home Rule. Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill was rejected in the House of Commons when a section of his followers voted with the Conservatives to defend the Union with Ireland. These Liberal Unionists comprised not only Whigs, like Lord Hartington, with their (small c) conservative affinities, but also a dissident group led by Joseph Chamberlain, who remained a (small r) radical throughout his career. The point was that they sank their other differences in a common hostility to the substantive proposal on Home Rule and were prepared to make the Gladstonian/Unionist division into the fulcrum of British party politics.

In 1916 Asquith’s coalition government, in which he had carefully contrived a Liberal dominance, was challenged by Lloyd George, with the acquiescence of most Liberal backbenchers and the support of the Unionist leadership. Their common view was that under Asquith’s direction – or lack of it – the war would be lost, whereas it could be won under an alternative government led by Lloyd George. Though the shape and permanence of this split took time to emerge, by 1918 it was clear that the new division in politics was between the supporters of the Lloyd George Coalition and its opponents, Asquithian and Labour alike.

The 1931 crisis saw the fall of MacDonald’s minority Labour government, not so much because it lost the support of the Liberals on whom it depended in Parliament as because of a cabinet-level split over measures to deal with the financial emergency. MacDonald and a handful of ministers joined with the Conservatives and most Liberals (except Lloyd George) to support a package of cuts in government spending in August 1931. On this at least they were all agreed, even though differences over other measures, especially tariffs, were to fracture some of the Liberal support. Though the ostensible object of the exercise – to save the pound sterling – was in fact the first casualty, when Britain was forced off the Gold Standard in September 1931, the political coherence of the National Government dominated British politics, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, for the rest of the decade.

In fact, it took another crisis, even more desperate, to upset this equilibrium. For in 1940 it was the manifest collapse of the Chamberlain Government’s war strategy which led to open revolt by its backbenchers. They knew perfectly well what they were doing: signalling then loss of confidence in Chamberlain and their readiness to support an alternative administration. When this was formed under Churchill’s leadership, it consolidated the political alliance between dissident Conservatives, Liberals and Labour which had been immanent since the breakdown of the Munich Agreement.

Now in each case, what happened was essentially the same: the governing party split when either its leaders or a crucial number of its supporters made common cause with the opposition, thus creating a new political axis which offered a coherent basis for an alternative government, committed to an alternative policy on the leading issue of the hour.

What happened in 1903 was not like this. True, the Conservative (or Unionist) Party became disunited, in the Parliamentary lobbies as much as in the country. The cause of the trouble was tariffs. For fifty years the Conservatives had swallowed the Free Trade orthodoxy, as established under Peel, and subscribed to the cross-party fiscal consensus. Suddenly all this was challenged by Joseph Chamberlain. His policy of TariffReform was aptly called a crusade. Built around his charismatic leadership and amplified by every trick of the media, it imported a strident ideological note into Conservative politics. It was a revolt of the radical Right, pursued through ‘a raging, tearing propaganda’ which shook the Party to its foundations. In short, and in hindsight, it was a premature case of Thatcherism. Compared with Chamberlain, the prime minister, Arthur Balfour, looked like a wimp, producing a series of backtracking compromises designed, however ineptly, to keep his followers together. Some Tory MPs crossed the floor – Winston Churchill among them – and took the Liberal whip because of their Free Trade convictions. It was on this moderate flank that the Party was vulnerable, not on its extremist fringe.

The present crisis is obviously more like 1903 than any of the others. There is no doubt that the fiscal issue divided and damaged the Edwardian Conservative Party, just as Europe has done recently. When the next General Election came in 1906, it swept the Conservatives to their biggest electoral defeat of the 20th century, transforming the prospects of the Liberal Opposition which many people had been ready to write off only a few years previously. But all this came about indirectly and in the course of time, not through a sudden-death confrontation. Faced with his irreconcilable radical wing, Balfour knew they had ‘nowhere else to go’ – and they knew he knew.

So the Government was able to stumble ingloriously from one Parliamentary expedient to the next, in a rearguard action which enabled it to cling to office for the length of a normal parliament. Balfour was reduced at one point to leading the Conservative Party out of the House of Commons in face of a Liberal motion which would otherwise have exposed its deep disagreement over Free Trade. But the one thing that Balfour did not have to fear was that the Tariff Reformers would make common cause with the Liberal Opposition. If it came to an issue of confidence, he still had his majority. With whatever private contempt, the radical Right would support the Prime Minister – to anticipate a famous phrase – like a rope supports a hanged man.

The fact is that governments do not fall on procedural tricks, paving motions or exercises in ingenious drafting. The writing on the wall does not appear in small print. An effective challenge requires effective challengers. They need to share a common perception of the issue at stake, a common agreement on its overriding priority, and a common readiness to face the consequences of bringing the government down. In 1992 these conditions have not been satisfied: hence the Government’s survival.

The Liberal Democrats have been much criticised. True, many of their supporters will have felt pangs at the thought of propping up Major. But they alone have posed the right question in clear and consistent terms. They stated that if the issue were Maastricht they would vote Aye; if the issue were Major they would vote No. In baldly taking the latter view, Labour was giving the Government the chance to run for cover under the confidence umbrella. Major has been forced into the position of publicly insisting that the issue was Maastricht, while his henchmen have privately been telling backbenchers that the issue was Major. A senior minister came out with it at the last moment: ‘The choice for the rebels is either to take Maastricht with John Major, or to have it – with social chapter knobs on – from John Smith.’

Maastricht and Major thus remain separate issues, with different opponents, who have contrasting motives and incompatible objectives. The Labour Party knows that it does not have a plausible alternative to Maastricht, still less one on which it could join hands with the Tory rebels. A thought-experiment makes the point: what post was John Smith thinking of offering Lord Tebbit in the new administration? The Conservatives, conversely, though pretty disillusioned with Major, know they do not have an alternative candidate as leader of an alternative government. He is now reduced to the status of the best prime minister they have – as was said of Eden, and perhaps of Balfour.

Major’s legacy, it should be said, was unenviable. What he was left by the Thatcher Government was not an economic miracle but a miracle of mismanagement. This is what makes the sheer brass neck of the Thatcherites during recent weeks so intolerable and rules out any rationale for co-operation between them and the opposition. Now that Nigel Lawson has spilled some two-thirds of a million words in offering his own account of that era, we can share ‘the view from No 11’ with him. Lawson admits that he may have been ‘slow to recognise the inflationary threat in the late Eighties’, when he was still stoking up the boom in an intoxicating binge from which we are even now suffering the hangover.

‘I have no doubt that I have made my share of mistakes,’ Lawson told the House of Commons in his resignation speech in 1989. Alas, the self-abasing passages, replete with abject contrition, which readers will naturally expect, have so far eluded me. But it can be reported immediately that Lawson’s fear, back in 1987, that ‘I might have made the wrong choice of Chief Secretary after all’ was dispelled when John Major (‘ashen-faced’) showed that ‘he was thoroughly on top of the job.’ This is comforting for those who have suspected that Major has recently had more than ash on his face in his new job. It reminds us of how deeply the Prime Minister has been implicated in the Conservative Government’s economic strategy throughout the last five years. This is the record which he will have to live with, Maastricht or no Maastricht, and the record on which the opposition can bring him to book.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.