Three African writers, from very different parts of the continent – Saro-Wiwa from Nigeria, Ndebele from South Africa, Macgoye from Kenya. My ignorance of all three regions being deep and extensive, I am obliged to accept these three books in great part as documentary reports, as information about unknown ways of life. But perhaps this is right. One of the many problems for an African writer in the English language is the question of his audience. Who is he writing for? For his own people – for the small fraction of his own people who will ever be able to read him? Like Joyce, ‘to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race’? Or is it his task to inform the rest of the English-speaking world about a continent still dark to those outside it, about its hopes and its fears, its ambitions and its stagnation, its advance and its relapse? The latter must be a large part of his intention. Yet this confronts the reader with the social and political history of a hundred tribes and a dozen emergent nations of which in the nature of things the outsider can have only a faint and distant understanding.

Ken Saro-Wiwa’s extremely accomplished collection of short stories stands to Nigeria in something of the same relation as Joyce’s Dubliners to Ireland. They are brief epiphanies, each crystallising a moment, a way of living, the whole course of a life. When as a youngster I first read Dubliners I remember being baffled by the way eerie characters and their bizarre motivations were calmly accepted as part of the ordinary nature of things. Saro-Wiwa’s tales bring back something of this feeling. There is great variety in these glimpses. The book is divided into two parts – innocence and experience, you might call them. The first part deals with Dukana, a village community, the second with the more sophisticated life of the towns. Not that there is anything idyllic about the village; it is sunk in dirt, apathy and superstition. An educated girl comes back there, thinking of it as home, and eager to see an old friend from schooldays. But she finds the friend has disappeared, been driven out, no one knows where. She has committed the misdemeanour of having twins. A solitary man who talks to nobody but gets on with his farming by himself is suspected of witchcraft, simply because he is a loner, and is burnt alive in his hut. Yet all the families are close and affectionate; and an element of placid bargain-keeping does something to mitigate the harshest arrangements. A beautiful girl is married, and married well, since it is to a lorry-driver: but she turns out to be barren and so is repudiated – with the agreement of all, including the girl herself. She simply pays back her bride-price, goes back to her mother, and resumes her life as before, without resentment or disgrace. Less sombre are the vagaries of the Holy Spiritual Church of Mount Zion in Israel, and the complex arrangements to defeat the Sanitary Inspector – involving, of course, the defeat of all attempts at sanitation.

This brings us on to Part Two, where the towns, repositories of government and business, are exposed in all the depths of their squalor, incompetence, chicanery and corruption. Some of this is the stuff of comedy: in the negotiations about the Acapulco Motel muddle and cheating seem to be tolerantly expected on all sides. But in the two stories ‘The Stars Below’ and ‘Night Ride’ we get a steady look at the heartbreaking hopelessness of this society. In each case an idealistic young official surveys the ruin of his life, the wreck of the world around him in the aftermath of a ghastly civil war, and the doubt whether the old apathetic stagnation or the new conscienceless greed is worse.

But I have made these stories seem more sombre than they are. An unlovely world, but much of it is rendered with affection; and there is immense satisfaction for the reader in the adroitness and variety of the presentation. A few of the tales are in pidgin, which I can hardly judge. Others use interior monologue and make a wonderfully happy accommodation between the idiosyncrasy of the characters and the decorum of the English language; while the parts where the narrator speaks in his own person have a straightforward elegance that is extremely attractive.

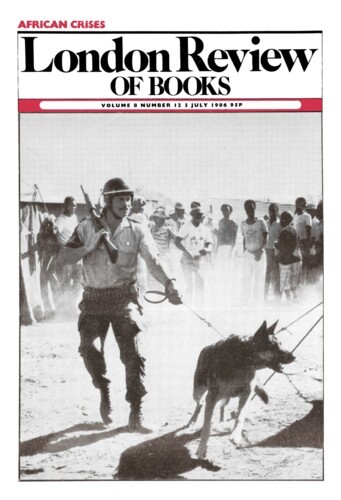

Though the colonial past of Nigeria is not very far away, it plays little or no part in the awareness of Saro-Wiwa’s characters. The new regime is self-determined, and the new official class has so successfully appropriated the privileges of its colonial predecessors that there is no room for çi-devant resentments. Whatever the social results of this, the literary effects are benign. It means that the writer can get on with his own job without taking on the burdens of others. The situation of the black South African writer is totally different. Wherever he turns, the facts of oppression are brutally present and inescapable. His literature is inescapably a literature of protest, fuelled by social and political passion. Writers are acutely aware of this. ‘Too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of the heart,’ as Yeats said before them. In ‘Fools’, the title story in Ndebele’s collection, a young student radical speaks: ‘You see, too much obsession with removing oppression in the political dimension soon becomes in itself a form of oppression ... Somewhere along the line, I feel, the varied richness of life is lost sight of and so is the fact that every aspect of life, if it can be creatively indulged in, is the weapon of life against the greatest tyranny.’

Hungry Flames is a collection of black South African writing, mostly since the Fifties, and the remarkable thing about it is not so much the political pressure behind it as the many other aspects of life it manages to include. It could have been a hymn of racial indignation, but it is not. The exploiters of the hapless country girl in Gladys Thomas’s ‘The Promise’ are fellow blacks. In Mzamane’s ‘The Day of the Riots’ Venter, a white salesman, is caught in a black township on a night when whites have been killed. But he is saved by his black co-driver, who at considerable risk to himself and his family shelters Venter in his own house and ultimately drives him home. This is not out of fear or loyalty or affection: just that the white man is not a bad chap, no one really wants him to be killed, no one wants a white body lying about the place – so a small pool of temperate good feeling appears amid the general turbulence. This is a valuable collection; it includes 15 representative stories, an introduction giving a brief literary history of the period, and biographical sketches of the writers.

Ndebele’s stories show a consistent effort to encompass ‘the varied richness of life’ even under the perpetually looming shadow of apartheid. His field is the black townships like Soweto, especially the life of the middle class. He is particularly successful in showing, beneath the squalor and constriction, the manifold humiliations and discomforts, that a very full and complex life is going on. The women characters are prominent. As one of them remarks, there are no outlets for an educated African woman but to become a teacher or a nurse. Most of Ndebele’s women are one or the other. But his characters are far from being racial or professional stereotypes. The protagonist of ‘Fools’ is a disgraced schoolmaster who drinks, fornicates, neglects to go to staff meetings and is always on the point of being sacked. Yet he is clearly a man of high intelligence who sees through everything around him, including his own failure. The thread of the story is his obscure, complicated yet absolutely authentic relation with a young student activist. It ends in humiliation and defeat, but a trickle of life has flowed through the system on the way.

In this world there is an undertone of conflict between the cultural ambitions of aspiring black families – aspirations which are, after all, purely white and European in their origin – and a profound suspicion of any mere aping of white values. In ‘The Music of the Violin’ a small boy is pushed on by his socially ambitious mother to the genteel accomplishment of learning the violin. He is quite good at it, and at first it seems that the introduction of a little Mozart and Brahms into the location could only be of benefit. But it turns out that the child hates playing the violin: he wants to play in the street with his friends. He is made to take the detested instrument to school, where he becomes an object of mockery. Finally he bursts out with all this, to the vociferous disgust of his parents; and the whole cultural façade collapses in a primitive and vulgar row. This is all part of Ndebele’s conviction ‘that too much of the real and imaginative lives of Africans has been given away to the oppressor and his deeds.’ The duty of the writer, as Ndebele sees it, is the difficult search for cultural autonomy.

With Coming to Birth we move to what seems a simpler world: Kenya in the years of its emergence as a separate nation. The coming to birth of Kenya forms the background, but the parallel foreground story is the coming to birth of Paulina Were as an autonomous being, from her start as a frightened young bride to her maturity as a grown woman, able to stand on her own feet, take charge of her own life and command a certain degree of security and happiness. For this is a success story, something rare out of Africa these days. Paulina comes from a small village near a small town, and the setting of the novel divides between this rural backwater and Nairobi, where she arrives as a bewildered 16-year-old to join her new husband. He is a clerk, poor and ashamed of the wretched room and sordid surroundings which are all he has to offer her. It is not much of a marriage. Martin is not particularly affectionate nor particularly faithful, and as Paulina turns out to have no children she is in no position to ask for anything better. Yet gradually a touching picture emerges of a quietly courageous young woman, able to make friends of her own, learning the ways of the baffling city, the skills expected of a city wife. She drifts away from her husband and goes back to the village, as is often the way with her people. She enrols in a homecraft school and sets up as a teacher to the country women. She has a child by another man, but the child is killed at the age of two in inter-tribal fighting. And when she goes back to Nairobi it is not as a victim or a passive sufferer, but as an independent being. The pictures of village life and the bustling multiracial confusion of Nairobi are both vividly done, and cleverly fused with the country’s possession of itself, its rise to a historical personality. The emergency and the subsequent inter-tribal fighting are lightly dealt with – at a distance, as Paulina sees them, and all subordinated to her point of view.

Martin in the meantime has taken several casual ‘city wives’, and Paulina has made a life for herself, like a New Woman in 19th-century Europe. But the bond between them still persists, and in Nairobi they begin to come together again, this time with the hope of a child at last. It is easy to see that this is a novel on entirely traditional lines. A young woman confronts her destiny, with little to help her but courage and persistence – like any heroine of Charlotte Brontë or George Eliot or Henry James. She makes her way with touching serenity through a country which is in a state of turmoil and ferment. Not at all ‘feminist’, but a striking statement of the cause feminists have at heart – and all the more striking for the unobtrusive distinction with which the story is told.

After the full-bodied African scene there is something slightly anorexic about much current fiction, particularly perhaps about the nouvelle, a form which is apt to suffer from under-nourishment. On the analogy of the nouveau roman Gabriel Josipovici’s Contre-Jour should be classed as a nouvelle nouvelle, for he still owes allegiance to that venerable tradition. Were the cats and the dog put down before or after the mother’s death? We are told both. Why, when the central theme is the relation of mother and daughter, does the mother suddenly announce that she is barren and has had no child? Why is the letter from the father announcing his wife’s death signed Charles when his real name was Pierre? Because this is a nouvelle nouvelle we are to be reminded by these hiccups in the narrative that we are reading fiction and there is no through road to fact. The disclaimer is all the more needed because Contre-Jour has a biographical foundation. It is well-known that the wife of the painter Pierre Bonnard had a passion for taking baths, only equalled by his passion for painting her in the nude. The result was a long series of paintings, of exquisite hazy luminosity, of Madame Bonnard either in the bath or entering it or emerging from it. Josipovici, with what biographical authority I do not know, bestows on them a daughter who feels herself totally excluded from her parents’ life by their narrow and obsessive relationship. Soon she is indeed excluded by being sent away to school. The mother in her turn feels that she has been rejected by the daughter from the start. Meanwhile the father-husband-painter says pretty well nothing to either of them and gets on with his painting, to which everything else in the house is sacrificed. It is this bleak and comfortless situation on which Contre-Jour is based. It is called a triptych, but that must be to puzzle us, for the third member consists only of a half-page death announcement. Effectively the book is in two parts, the first the interior monologue of the daughter, the second that of the mother. They are in flat contradiction to each other. Each feels her life to have been ruined by the other’s indifference and neglect; and the only thing clear is that both lives are ruined. Each is convinced of the absolute rightness of her position, and both monologues have an obsessional force. It is at times suggested that the key to this stagnant imbroglio is the attitude of the father who refuses to engage himself in anything but his work. But he remains a shadowy figure, his one revealing remark showing him as entirely wrapped up in organising visual sensations: ‘But it won’t do to impose tension. It must spring from the subject. Otherwise you get expressionism, with every picture the same, the world transformed into the artist’s anxieties.’

Curiously enough in a book about a painter, the visual quality is almost wholly absent from the writing. Josipovici gives a powerful rendering of anxiety and obsession, but of the untroubled dream of light and colour in which Bonnard seems to have passed most of his life we get no impression at all. One cannot doubt that this is deliberate, as everything else in this discourse seems to be, and the writing is far too skilful to strike an unintended note. But the impulse behind it remains obscure to me. Perhaps I have misread something, or missed some signpost.

The dust cover of The Seven Ages tells us that in this novel Eva Figes presents the history of mankind. The book contains 186 pages, which seems a bit slim for the history of mankind, even if it is, to quote the cover again, ‘seen from a somewhat different angle’. You will never guess what that angle could be, so I will tell you. It is ‘the woman’s point of view’; and the history of mankind turns out to begin in Anglo-Saxon England, and then to jump in seven chapters through the Medieval world, the Reformation, the Civil War, the 18th century, Victorian times, and, after a quick glance at World War Two, to finish up on Greenham Common. But the structure is more complicated than this would suggest, and there is a framework to these historical vignettes. The linking character is a woman who has just retired from her job as a midwife and gone to live in the country, in the village where she was born. While establishing herself in her cottage she begins to hear voices – voices from the past. Whether the speakers are genetic ancestors or spiritual predecessors is not clear. But they come and go – happily, for lucidity, in chronological order – and discuss such matters as obstetrics (at inordinate length), herbal medicine, witch-hunts, suffragette riots and family planning. Rather like an Old English version of the centre pages of the Times. The large-scale narrative is interspersed with recollections of the protagonist’s own childhood, which from the beliefs and manners described seems to have been passed in the late Middle Ages, though if you work it out it must have been around 1930. There are supporting characters – the woman’s two grown-up daughters, one bossy and scientific, the other unaggressive and folksy. They form the link with the current scene.

It will be evident that this is an ambitious scheme. And with all due respect to Eva Figes’s previous achievements, some of which are distinguished, I am bound to say that it does not come off. The history gets perilously near to the 1066 and All That variety; the characters, such as they are, come straight from stock. They are not properly introduced, so that half the time we do not know who, what or where they are supposed to be. A spurious air of mystery is suggested by litanies of the names of herbal remedies – southern-wood, napweed, comfrey, scabious and mugwort, mugwort all the way. And when the sick are healed by a decoction of St Hilda’s toenails I really do not know what I am supposed to think about it. Eva Figes has shown herself remarkably penetrating in the psychological byways of our own time. When it comes to the past she falls too easily into stereotype and convention.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.