The most successful pieces in Norman MacCaig’s Collected Poems tend to be lists of one kind or another. He is best, too, when he has found something to celebrate. A poem such as ‘Praise of a Collie’, which enumerates the virtues of an admired sheep-dog, now dead, works well enough as a primitive catalogue. The fourth of its five three-line stanzas gives something of its flavour:

She sailed in the dinghy like a proper sea-dog.

Where’s a burn? – she’s first on the other side.

She flowed through fences like a piece of black wind.

The abruptness of these jottings seems to relate the poem to an ancient style of praise-singing that one is glad to see revived here, and the inconsistency of the tenses is a positive bonus. The hyperbolic flourish of ‘like a piece of black wind’ is perfectly suited to the purposes of an obituary, allowing the dog to live again, ‘neat and fluid’, for as long as the lines remain in one’s memory.

MacCaig’s habit of recording natural phenomena by means of surprising simile and metaphor is perhaps his greatest asset. Intimacy with the landscape of North-West Scotland, its weather, its flora and fauna, and – to a lesser extent, one feels – its human inhabitants, has provided the material for most of his best work. Where he has been content to operate within a modest scale and has refrained from chasing the metaphysical ignes fatui that bedevil so many of his ostensibly more ambitious pieces, he has scored some remarkable successes. Poems such as ‘Fetching Cows’, ‘Movements’ and ‘Notations of Ten Summer Minutes’, which aspire to be not much more than inventories of casual observations, are nonetheless richly enjoyable. Admittedly, even these have their slacker passages: in ‘Fetching Cows’ one is disappointed by a phrase like ‘muzzles black and shiny as wet coal’, but the poem recovers triumphantly in its final stanza. ‘Far out in the West,’ we read, ‘the wrecked sun founders though its colours fly’; and its very last lines –

The black cow is two native carriers

Bringing its belly home, slung from a pole –

are an ideal blend of the comical and the exotic.

The playful, humorous, genially delighted side of MacCaig’s poetic personality is one that many of his readers may wish he had cultivated more assiduously. It is this that lends distinction to poems that otherwise squander their energies in laborious, quasi-philosophical word-spinning. In ‘Rhu Mor’, for example, from the book Rings on a Tree (1968), the poet attempts to capture a visionary insight in the lines:

Space opens and from the heart of the matter

sheds a descending grace that makes,

for a moment, that naked thing, Being,

a thing to understand.

The poem’s true vision, however – the perception that holds its own long after this barely supported assertion has been forgotten – is contained in the passage where a seal is observed ‘struggling in the straitjacket of its own skin’. How much more authentic this experience is, and how much more vividly we are made to feel it! Just so, there is a poem from the same book, ‘Now and for ever’, which offers itself as an elliptical meditation on the nature of experience, but which fails to register any palpable impression until, finally, the poet claps eyes on

a rock where

a cormorant, wings half spread, stands

like a man proving to his tailor

how badly his suit fits.

Metaphors of this kind carry the impact of metaphysical conceits in miniature. They are vastly more effective than the pages of fustian rhetoric and logic-chopping which constitute so much of MacCaig’s total output. From a consecutive reading, it becomes apparent how much of this has been devoted, commendably enough, to an inquiry into the problems of identity, or selfhood. The word ‘self’ turns up again and again. In ‘Purification’, from A Round of Applause (1962), he addresses an unspecified second person with the words:

Wearing yourself as though it were

The lightest of all garments, moving

As though all answers were a mode of movement,

You came and were as though to be were easy.

By contrast, he exhibits himself as having dwelt on the question of identity with immense seriousness. A Man in My Position, the title of his eighth book (1969), refers to the Borgesian notion that ‘some appalling stranger / who makes windows of my eyes’ is inseparable from any consideration of his inner being. Other verbal formulations – ‘my mind observed to me’; ‘My own self / Is what surrounds me and it trembles / With my own winter’; ‘The chaotic possibility of being me’ – bang the point home.

Unsurprisingly, this preoccupation is inclined to colour MacCaig’s account of the world that exists beyond the enigma of his psyche. The hampered seal and the dissatisfied cormorant are imaginatively contrived projections of the idea, but there are as many instances where the poetic transaction fails to come off. ‘It stands in water, wrapped in heron,’ MacCaig tells us of – a heron. And he goes on:

It makes

An absolute exclusion of everything else

By disappearing in itself.

Elsewhere we find such utterances as ‘High in air, the air / Lies like an open secret’ and ‘it was water / falling sixty feet into itself’ – this last serving as a description of a water-fall. Vagueness, tautology and bathos are the almost invariable consequences of the rhetorical trick employed here. As it happens, there are grounds for supposing that he believes all descriptive effort to be dauntingly hazardous, even futile. ‘I can no more describe you,’ he insists at one point, ‘than I can put a thing for the first time / where it already is.’ But is this strictly true? Metaphor, as he of all writers should not need to be reminded, can provide a means of coping with the problem, and when he applies it skilfully he answers his own quibble with decisive effect. Yet it appears that there has always been something in his make-up, some Calvinist inhibition, that has prevented him from wholeheartedly enjoying the device, and thereby from using it with consistent flair. It is chilling to read in ‘No Choice’, the bleak little cri de coeur with which he ends Rings on a Tree:

I am growing, as I get older,

to hate metaphors – their exactness

and their inadequacy.

Surely, one wants to reply, it is just this ‘inadequacy’ that gives metaphor its peculiar poignant force? And surely the man who once described a snow-smothered tree as being ‘hugged by its own ghost’, and a hilly landscape as ‘Distances looking over each other’s shoulders’, knows this perfectly well?

In the frequent absence of metaphor from these poems, therefore, what we are offered instead tends to be a brand of sophistical discourse. What is one to make of a sentence like this?

For mile and moment are no larger than

Each other is.

Apart from advertising the poet’s familiarity with the concepts of space and time, what does this self-cancelling statement actually tell us? Can it be said to mean anything? These are questions for which the poem itself (‘Information’: Riding Lights, 1955) yields little by way of helpful clues. And when in ‘Moor Burns’ (The Sinai Sort, 1957) MacCaig describes the effect of light on a landscape as ‘placing in air / Precisely this precisely there and that / In a place made due to it by planes of light’, what does this exercise in logical circuitousness really achieve?

These examples are taken from early volumes, but the habit has been damaging to much of MacCaig’s later work as well. In ‘True Ways of Knowing’ (Measures, 1965) we are given to understand:

The way that flight would feel a bird flying

(If it could feel) is the way a space that’s in

A stone that’s in a water would know itself

If it had our way of knowing.

The two blatant logical escape-routes supplied here by the repetition of ‘if’ have their counterpart in the negative that squats like a black hole, swallowing everything, in the middle of a sentence from ‘Solitary Crow’ (Rings on a Tree):

Where he goes he carries,

Since there’s no centre, what a centre is,

And that is crow, the ragged self that’s his.

‘It was the place that it was in / And was in what the place was’ is how a verbal sketch of a reclining figure by Henry Moore begins (A Man in My Position); and for a specimen of his tangled line in love-poetry one could hardly improve on a snippet from ‘Morning Song’ in The World’s Room (1974), where the loved one is treated to an especially problematical earful:

I want to tell you

how impossible it is

not to tell you how impossible

it is to tell you of the mornings

you make of this morning.

Anyone investigating MacCaig’s Collected Poems, assembled from thirty or more years of copious production, is obliged to confront the puzzle of their unevenness. Of course, one appreciates what is good: the precise observations, the lively metaphors, the occasional droll jokes, and those passages, some of them amounting to entire poems, where a genuine experience of the world is faithfully transmitted. But this is a small part of a large output, and against it stands much that is dismayingly inferior. MacCaig’s first volume demonstrates his struggle with poetic form, a struggle which he has not often, it seems to me, resolved satisfactorily. The poems contained in Riding Lights evidently spring from a knowledge of Shakespeare and the great Metaphysicals, to which a touch of Thomas and a smack of Empson have been added for modernity’s sake. The effort to be colourful at all costs leads to such expressions as ‘the dank grass is tangled with the song / Squirmed from a blackbird by the probe of light’ (‘The Rosy-fingered’), and ‘I cannot stammer thunder in your sky / Or flash white phrases there’ (‘Fiat’). Stilted grandiloquence and mythic gestures abound. Syntax is often contorted, and the main point of many of the poems seems largely to outdo ‘The Extasie’ in argumentative knottiness.

This strenuous manner survives through several volumes, until it begins to relax about the time of Measures. The most recent volume, A World of Difference (1983), shows MacCaig at his most unbuttoned. Procrustean stanza-forms, in which the poet was never sufficiently at ease, have been abandoned in favour of a metreless, sometimes even rhythmless, system of line-breaks. Rhyme has vanished, sentence structure is virtually conversational and the language, stripped of its Jacobethan trappings, has been rendered nearly as tame as prose.

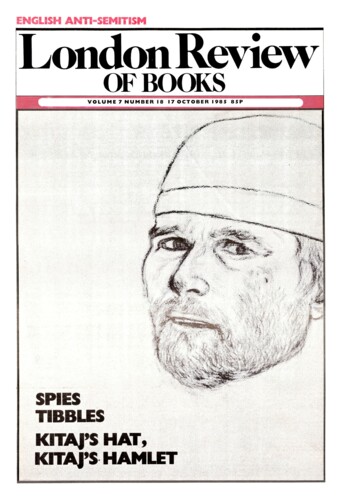

Does this mark a laudable improvement then? The old strained manner was hard to take, but the new loose one is exasperating in its own way. A kind of attudinising is evident in both, demonstrating the poet’s wish to pass as a seasoned operator in the world of myths and big ideas. In an early poem, ‘Harpsichord playing Bach’, the pronouncement that ‘space and time are those two clowns whose act / Seems all disruption’ is meant, presumably, to reveal how MacCaig can put even the most fundamental concepts in their place. Later poems exhibit a similar swagger. ‘Moses never thought of this,’ MacCaig says in ‘City Fog’ (A World of Difference), ‘when we chatted with the Lord / on that funny mountain.’ His demeanour among the archetypes of European culture is notably free of awe. Mercury is referred to, in passing, as ‘god / of debit and credit and inventor / of double-entry book-keeping’; the play of Hamlet is reduced to a matter of ‘gothic glooms and ghosts and garrulities’; of Daedalus it is asserted that he ‘made a mousetrap / and his PRO man / called it a labyrinth’; while Penelope, Zeno, Columbus and William Blake are treated to comparable familiarities.

Parables on the futility of artistic endeavour – ‘Nothing too much’, ‘Portrait Bust’ – are a recurrent mode. Intellectual aspiration of any kind is subject to automatic suspicion, and academics in particular come in for some of MacCaig’s least considered satire. This does not prevent him from indulging his own kind of pedantry, however, even in what are presented as amorous lyrics. In ‘Drifting in a Dinghy’ (The World’s Room) he confesses:

I can no more analyse

the syntax of your going or parse

your parts of all speech

than I can explain why music

is a narrative of all illuminations except

yours, even though I can’t tell

an organum from

a diminished clavichord.

Using this sort of language to renounce analysis strikes me as not very different from throwing out the baby and keeping the bathwater, but it is symptomatic of MacCaig’s strangely ambivalent attitude to the art he practises.

‘I see her coming,’ we are informed at the end of a piece called ‘Impatience’ (The Equal Skies, 1980),

and walk towards her

out of this trash of metaphor

into the simplicity

that explains everything.

The poet’s belief that he has solved his problem is not, however, likely to be shared by the reader, whose frustration only increases in the face of page after page of poetic abstention. ‘The woodcock I startled yesterday,’ MacCaig says in ‘Woodcocks and Philosophers’ (A World of Difference),

clattered off through the birch trees

without starting to philosophise

and write a book about it.

This unastonishing reflection proves to be the beginning of yet another niggle at the expense of intellectuals. The woodcock itself, which in earlier days might have prompted some of the poet’s brighter similes and metaphors and come alive through the magic of words, has a merely nominal role in this context, being obliged to take second place to a tired old grouse. Again and again one is compelled to lament MacCaig’s neglect of his true, fine gifts.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.