With the deaths of Thomas Mann in 1955 and of Bertolt Brecht and Gottfried Benn in 1956, a major era in the history of German literature comes to an end. These three are not only the greatest writers of their age, they are also its witnesses. Each of them worked in a different genre: Thomas Mann in the convoluted, partly essayistic prose of his novels, Bert Brecht in the drama and narrative poetry of social dialectics, Benn in the lyrical poetry of radical Modernism. Each went through a different political development and reacted differently to the ruling political ideology. Yet the questions they ask have a family likeness; and the answers they offer remind us forcibly that theirs was an age of terror.

Any author whose literary gifts and moral disposition lead him towards this contemporary turmoil and who tries to come to terms with it creatively, with the best that is in him, is bound to have to face very special formal and compositional problems. These problems are likely to be different for a writer like Günter Grass, who faces the same world at one remove, reporting on the way the dead buried their dead. This is our first premise. The other is that, quite irrespective of that era, the German novel at its most characteristic has not been renowned for its contributions to the ‘Great Tradition’ of European realism, which dominated French, English and Russian prose literature throughout the 19th and well into the 20th century. Realism as we know it from Stendhal, Dickens, Tolstoy onwards entered German literature relatively late in the day and has been powerfully challenged by other modes of writing. Thus Thomas Mann’s very last work, the unfinished Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man of 1954, is a picaresque novel whose main narrative devices are a direct challenge to the verisimilitude of realistic fiction.

Chief among the literary and cultural patterns of Thomas Mann’s novels had been the classical German Bildungsroman, the novel of initiation and development, in the course of which a young hero is led from adolescent self-absorption and egocentricity on the margins of the social world through a variety of instructive experiences – often a mixture of the erotic and the aesthetic – to a state of adulthood and responsibility at the centre of contemporary society. True, Thomas Mann’s use of the Bildungsroman and its main theme had never been unambiguous and unproblematic, had always been informed – or undermined – by a spirit of irony: in Felix Krull this is radicalised to a point of fantasy and farce.

The pattern from which Krull evolves is the picaresque novel which, in German literature, goes back to the 17th century: 1668, to be precise, when Hans Jacob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen published his Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus, a novel which, in sharp contrast to the contemporary courtly novel, is set among soldiers, actors, servants, beggars, robbers and whores. There are characters exemplifying the Christian virtues, but the notion of moral and spiritual development recedes behind a rich and colourful series of adventures on the pattern of ‘one damn thing after another’. Purposeful teleology gives way to the rule of fortune, spiritual uplift goes hang, cunning for the sake of mere survival is the order of the day, and when salvation does come, it comes in as untoward and unmotivated a manner as do the temptations of the flesh and of the devil. All this, as we shall see, is grist to Günter Grass’s mill. The picaro he will create from some of the elements of the traditional rogue novel is as radical a response to Thomas Mann’s genteel Felix Krull as Krull is to Grimmelshausen’s Simplicius. Very strong affinities of atmosphere connect the Germany of the Thirty Years War, which Grimmelshausen portrayed, with the Germany of the 1930s and 1940s which is the obsessive concern of Grass’s ‘Danzig Trilogy’. These are affinities which are not encompassed by Mann’s imagination, or by the imagination of many writers of Mann’s generation apart from Brecht.

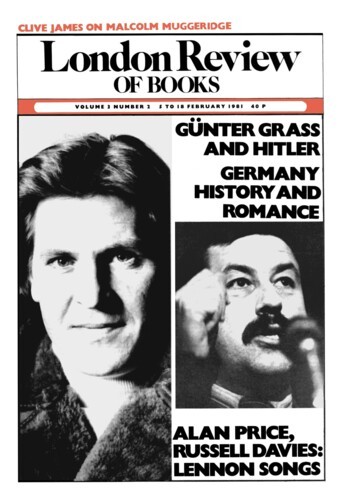

Günter Grass was born in a suburb of the Free City of Danzig in 1927, then under the protection of the League of Nations, and like Charles Dickens, Jan Neruda, James Joyce, Theodor Fontane and his acknowledged exemplar Alfred Döblin, he places his native city at the centre of his creative imagination. Grass’s best work so far is given over, again and again, to its evocation: a very special piety ties him to the streets and places of Danzig, its beaches, its inhabitants and their desperate, murderous national conflicts. For even more than the London, Dublin, Berlin and Prague of the authors I have mentioned, Grass’s Danzig is an intensely political city: the place, from the 12th century onwards, where Prussia and Poland, the Knights of the German Order and Polish patriots, Germans and Slavs encountered each other in rivalry. In 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany. At this time, when Danzig was experiencing growing unemployment, a deterioration of its maritime trade and an upsurge of nationalism, the people of the deeply divided city elected a Senate with a National Socialist majority and the local Party Gauleiter as its President.

To paraphrase a sentence of Brecht’s Galileo, happy is the country that has no land frontiers. With the conflict of Ulster in the forefront of our minds, we now find it less difficult to imagine the protracted bitterness and violence of the Polish-German relationship that is epitomised in the history of Danzig – the intensity of the passions, the internecine strife of centuries, which come to a head and lead directly to the outbreak of the Second World War in the first days of September 1939, and to the city’s death in the last week of that war. The rhythms of the threnody which the narrator-hero of The Tin Drum chants for the city illustrate that special pietas loci which informs Grass’s prose, and give us a first idea of its innovatory energy:

After that we seldom emerged from our hole. The Russians were said to be in Zigankenberg, Pietzgendorf, and on the outskirts of Schidlitz. There was no doubt that they occupied the heights, for they were firing straight down into the city. Inner City and Outer City, Old City, New City and Old New City, Lower City and Spice City – what had taken seven hundred years to build burned down in three days. Yet this was not the first fire to descend on the city of Danzig. For centuries Pomeranians, Brandenburgers, Teutonic Knights, Poles, Swedes, and a second time Swedes, Frenchmen, Prussians, and Russians, even Saxons, had made history by deciding every few years that the city of Danzig was worth burning. And now it was Russians, Poles, Germans and Englishmen all at once who were burning the city’s Gothic bricks for the hundredth time. Hook Street, Long Street, and Broad Street, Big Weaver Street and Little Weaver Street were in flames; Tobias Street, Hound Street, Old City Ditch, Outer City Ditch, the ramparts and Long Bridge, all were in flames. Built of wood, Crane Gate made a particularly fine blaze. In Breechesmaker Street, the fire had itself measured for several pairs of extra-loud breeches. The Church of Saint Mary was burning inside and outside, festive light effects would be seen through its ogival windows. What bells had not been evacuated from St Catherine, St John, St Brigit, Saints Barbara, Elizabeth, Peter and Paul, from Trinity to Corpus Christi, melted in their belfries and dripped away without pomp or ceremony. In the Big Mill red wheat was milled. Butcher Street smelled of burnt Sunday roast. The Municipal Theatre was giving a premiere, a one-act play entitled ‘The Firebug’s Dream’. The city fathers decided to raise the firemen’s wages retroactively after the fire. Holy Ghost Street was burning in the name of the Holy Ghost. Joyously, the Franciscan Monastery blazed in the name of St Francis, who had loved fire and sung hymns to it. Our Lady Street burned for Father and Son at once. Needless to say the Lumber Market, Coal Market and Haymarket burned to the ground. In Baker Street the ovens burned, and the bread and rolls with them. In Milk Pitcher Street the milk boiled over. Only the West Prussian Fire Insurance Building, for purely symbolic reasons, refused to burn down.

The fate of the city and its surrounding countryside becomes, for a boy born of a German father and a Cashubian (Slav) mother, a part of his intimate personal history. As a member of the German lower middle class that was particularly receptive to the new racist and nationalist ideas, at the age of ten he entered the ‘Jungvolk’, from which he was promoted to the Hitler Jugend, joining a tank regiment as a gunner when he was barely 17. When, at the end of the war, on being wounded, he was taken prisoner-of-war by the Americans, he still felt, as he says, ‘that our war was all right.’ Then came the shock of a guided tour through the concentration camp at Dachau and the gradual realisation ‘of what unbelievable crimes had been done in the name of my... generation and ... what guilt, knowingly and unknowingly, our people had brought upon themselves’.

Here, then, are the elements present in this exacting setting: lower-middle-class life with its hybrid linguistic milieu and its charged atmosphere of rival nationalisms, with a small Jewish minority the butt of both sides, and a strong and highly ritualised religious tradition – in Grass’s case, Roman Catholic; the smells and shapes of a small grocery store; the Party – its ideological slogans, colourful ritual and sordid practice; school life, swimming in the Baltic Sea; the war in its last, hopeless stages; and the true face of the regime disclosed at last. On his release from the American PoW camp, aged 19, Grass does not go back to school but finds himself a job as apprentice miner in a potassium mine near Hildesheim, listening during the breaks for salami sandwiches to the last echoes of the political quarrels that had begun long ago, in the Weimar Republic, and in which embittered Communists and disillusioned and resentful National Socialists together ganged up on ‘the dry-as-dust’ SPD who ‘taught me how to live without an ideology’. Grass’s activism and his allegiance to the SPD date from those early post-war days before the German economic miracle, and this allegiance was later strengthened by his friendship with Willy Brandt. When, in December 1970, Brandt as German Chancellor went to kneel before the monument to the victims of the Polish resistance in Warsaw (a gesture that appalled the troglodytes on the far Right), Grass was among those who accompanied him. Yet he acknowledges, in his major works, the need to separate his fiction, not from politics, but from political advocacy. A strong political concern goes through his novels, a deep, mature and tolerant understanding for the predicament of the little man at the mercy of huge political forces. But his understanding goes further, beyond this sort of tolerance, to major satirical sorties against the trimmers and fellow-travellers and profiteers, culminating in that very special grotesque presentation of the horrors of war, and of totalitarian regimes, which yields the most remarkable passages of his prose so far and is his outstanding contribution to post-war German literature. The tolerance that informs his portraits of the lower middle classes must not obscure the fact that he is not content, as many of his contemporaries are, to present the predicament of the individual man as though it were caused by a stroke of fate: it is part of his purpose to show the political sources and consequences of that predicament.

After two years of mining, Grass became an apprentice in a monumental mason’s work-shop in Düsseldorf, and then, after a brief period in a jazz band, he won a scholarship to study drawing and sculpture at the academies of Düsseldorf and Berlin. He is a gifted draughtsman, and has produced some fine illustrations and the stunning designs for the dust-jackets of his books. After his time at the Academy he went, penniless, on a series of extensive hitch-hikes through Italy and France. It was in the course of these journeys that he seems to have moved, quite imperceptibly, from drawing and sculpture to writing, and from huge and impracticable epic effusions to prose-poems, and hence to a highly rhythmic and rich, metaphor-studded prose. To this day, the early plans of his novels tend at first to be set out either like blueprints in multicoloured graphs or in the form of brief, usually unrhymed poems.

Both the interest in the visual arts and the unfussy, easy way in which he moves from genre to genre – creating pictorial patterns and shapes in his literary fictions and complex literary allusions in his drawings – all this ease of transition between different kinds of creativeness is reflected in his prose. Not only that. These transitions have their parallel in the movement of his novels from the present to the past and back again, from the historical to the political, from the concrete to the abstract; and in the disconcerting and apparently arbitrary way in which he is apt to slip from the first-to the third-person narrative, from the point of view of one character to that of another, as though all men, even in their solitude, even in their moments of murderous enmity, were yet unable to deny the fact that they are made of one flesh, consubstantial, and as though the world of things, too, were solid yet not inanimate, an extension of the living substantiality of men. And all this, which I present here as though it were an abstruse, excogitated aesthetic doctrine, is of course nothing of the sort: it is, for him, a literary practice, extensively reflected on, which enables him to match and make his vision of the world. He was 17½ when the war ended in May 1945. The compulsion exerted on him comes, not from the events of the past, but from a recollection of those events. In Grass’s early novels it is converted into a prose which turns out to be the only major source of liberation from an unmanageable literary past that post-war German literature has known.

The past as time and life irretrievably lost, and the past in the light of the present; the grand guignol of history and the actuality of its politics; the complex relationship of eros and food, and the special place of the disgusting and the sentimental in the recesses, the oubliettes, of consciousness; the religious and the blasphemous, the pious and the obscene; things, animals and men, concrete objects and conceptual abstractions – all these parts of an acute sense of life are set out in Grass’s prose, not, however, in some ghastly Hegelian dialectic of antitheses and radical contradictions, but in continuities and prismatic rainbow patterns.

More than one critic has called Grass a humanist. I am not sure the word has much meaning left. He is one in the sense that there is no human experience too odd, too alien, to be made a part of one of his prismatic patterns. But he seems, as the author of certain substantial fictions, too diverse, too uncompromisingly interested in the fate of these fictions and in the process that gives rise to them – in short, too free – to be classifiable under any -ism or ideology. Literature is made of many different brews and dispositions, in freedom and in bondage, by the most doctrinaire no less successfully than by the least attached. But in his time and place – our assessment has the wisdom of hindsight – in that moment of defeat and dishonour, of shame and the posturing that tried to hide the shame, in that moment when the past could be neither forgotten (though it was denied) nor allowed to paralyse the present, a man without ideology was what was wanted, and Grass was and has remained that man. I mean here not Grass the political man and responsible Bürger of what has become one of Europe’s exemplary democracies, but Grass the author of the most passionately contended books in post-war German literature, books which were attacked, not just on moral grounds (like Ulysses or Lady Chatterley’s Lover), but also on political and patriotic grounds (like the works of Sinyavsky and Daniel): I mean the author of ‘The Danzig Trilogy’.

The three works – The Tin Drum (1959), the novella Cat and Mouse (1961) and The Dog Years (1963) – were not planned as a single whole: the collective title comes, as far as I know, not from Grass himself, but from a perceptive critic, John Reddick, who used it as the title of a study (1975). What the three works have in common is, above all, the locale and the historico-political theme of Danzig at war (a theme which, oddly enough, is not central to Reddick’s book). It is as if ‘the Hellish Breughel’, his attention caught by the intricate pattern of one of his own landscapes with figures, had decided to devote two further panels to the subject: one small, exploring a single detail, the other on a larger and less intimate scale than the original picture.

In the first work, The Tin Drum, Oskar Matzerath – inmate of a mental hospital, which he describes, rather more euphemistically, as ‘eine Heil- und Pflegeanstalt’, a sanatorium and nursing home – Matzerath is writing his memoirs. The time covered takes us from the bizarre scene when his mother was conceived under her Cashubian mother’s fourfold skirts in a potato field at harvest time in 1899, through Oskar’s own birth in 1924, through his arrest and hospitalisation 28 years later, in 1952, when (with the help of Bruno, his warden) he begins writing his memoirs, to his 30th birthday and the conclusion of his manuscript in 1954.

Narrative coherence, in The Tin Drums, is achieved by a complex but relatively unified point of view, the ‘I-he’ narration of Oskar Matzerath. In the novella Cat and Mouse (1961) – an adventure story of wartime adolescence, an offshoot of one of the episodes of the first novel – the point of view remains that of a single narrator, Pilenz, but because it is a confessional tale, involving a sequence of schoolboy jealousies and betrayals, the reliability of Pilenz as first-person narrator is constantly undercut. The truth of his narration remains as uncertain as does the character of the problematic hero and object of Pilenz’s betrayal, ‘the great Mahlke’ himself. German Novellen are built around a single momentous event. Here the event is Mahlke’s theft of one of Germany’s highest military decorations, the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. Every German schoolboy’s dream, a coveted toy loaded with immense mystical, patriotic and sexual connotations, that Knight’s Cross serves, in an almost physical sense, as the means of Mahlke’s desperate self-defence and arrogant self-assertion (as the tin drum does for Oskar Matzerath); its ambivalent function – it commemorates the Knights of the Teutonic Order, yet it is a creation of Hitler’s – corresponds to the narrator’s unreliability and unstable point of view.

Finally, and again emerging from the episodic material of The Tin Drum, the mammoth undertaking of The Dog Years (1963). This is the story (among a great many other things) of the friendship between Walter Matern, the son of a German miller from the Danzig hinterland, and the half-Jewish Eddi Amsel, alias Haseloff, alias Brauxell (in several different spellings). The account of three decades – from 1925 to the mid-Fifties – is presented by various authors, including a whole post-war collective of them in the pay of the now baptised Amsel-Brauchsel, the artist-entrepreneur-manufacturer of Art-Déco scarecrows, who (like most other characters in the novel) is in pursuit of a past he hopes he will never catch up with.

The coherence of The Dog Years is provided neither by the action nor by its characters: the discontinuous narrative, especially in the last section of the book, is a part of its programme – one might almost say of its ideology. The action is frozen into metaphors and images, which provide such unity as the book possesses. To say this, though, is liable to lead to a misunderstanding. Critics who point to the importance of images in novels often argue as though the patterns these images form were patterns in the book and nowhere else. This is called ‘non-referential’ – I think nonsensically. The genealogy of black dogs from which the book takes its title and which is reiterated throughout –

Pawel ... had brought Perkun with him from Lithuania and on request exhibited a kind of pedigree, which made it clear to whom it may concern that Perkun’s grandmother on her father’s side had been a Lithuanian, Russian or Polish she-wolf. And Perkun begat Senta; and Senta whelped Harras; and Harras [covered Thekla von Schüddelkau] and begat Prinz; and Prinz made history [because Prinz was given to the beloved Führer and Chancellor of Greater Germany for his birthday and, being the Führer’s favourite dog, was shown in the newsreels ...]

– this genealogical list, for all its symbolical overtones, is made up of the sequence of generations of actual SS black dogs and is the emblem of a historical experience. Similarly, the ontological blatherer with totalitarian collywobbles and attacks of authenticitis of the cervical membrane called Martin Heidegger is an identifiable caricature of the philosopher of that name; and the mountain made of human bones which lies between the outskirts of the city and the lunatic asylum at Stutthof, which everybody sees and nobody has seen, which everybody smells and nobody knows anything about – that mountain, expressed in Heideggerian gobbledygook, is ‘being that has come into unconcealment’ and ‘the ontological disposition toward the annihilating nothingness of German history’.

There is no end to the strings of bizarre images which create the unity of the book. They all raise the same question: why is there no continuous action? Why the bizarrerie? For an answer to this central question of Grass’s early work, we had better return to his first and most accessible novel, The Tin Drum.

Here, certainly, there is something like a central character, depicted with a modicum of psychological coherence – a coherence which is undercut, but not fatally, by that opening confessional statement made in the haven of a lunatic asylum. Oskar Matzerath is presented – and presents himself – in a series of unstable and unnervingly ambiguous relationships with the people and events around him, mainly victim but occasionally victimiser of a bizarre world, a ‘world upside down’. Even as an embryo, he anticipates that his entry into the world is bound to be disastrous – not because it is his entry, but because it is the world. (The heroes of the classical Bildungs-roman similarly hesitate whether to enter the social world or to remain safely hidden in the caul of their solipsistic imagination, but similarly, too, we read in one of Grass’s favourite novels: ‘My Tristram’s misfortunes began nine months before ever he came into the world.’) And when Oskar’s wish to return into limbo is not fulfilled (the midwife – I mean Oskar’s midwife, but it could be Tristram’s – having done the irreversible and cut the umbilical cord), Oskar does the next best thing: he throws himself through the trapdoor into the cellar at the age of three, and there and then wills himself to stop growing. End of Entwicklung with a vengeance.

What this fairy-tale of outrageous absurdity suggests is that there is no other way of coping with, and making sense of, the hideous events and encounters of the adult world, and also that this is really no way either, because, by becoming a freak with every appearance of a gravely retarded development, Oskar is liable to fall a victim of the state-controlled euthanasia action which the National Socialist regime practised in order to implement its racial policy: it is only the collapse of the postal service at the end of the war (when even the Prussian bureaucracy ceased to function) that prevents Father Matzerath’s letter, in which he consents to the eugenic killing of Oskar, from reaching what is so quaintly called the Reichs Ministry of Health. And this world, in which Oskar wills himself to stop growing, still pays lip-service to the Classical Weimar values of spiritual growth and development that had been central to the ideology of the Bildungs-or Entwicklungsroman.

These outrageous assaults on the reader’s sensibility dominate every part of the novel. Oskar has a mother who dies, hideously, of a surfeit of fried lampreys and eels, some of which, we are told, may be the descendants of those Baltic eels that may have eaten her Polish grandfather, assuming, which is never entirely certain, that he was drowned and didn’t disappear in the United States. Her death, like so many deaths in the novel, is the sign of a botched life. And Oskar has two fathers: an elegant Polish one, who is his mother’s lover, and a German one, the hefty grocer Matzerath, with whom he will eventually share a mistress. Jan Bronski, the Pole, is involved in ‘the famous battle for the Polish post-office’ at the outbreak of the War, which he spends playing a difficult game of three-handed skat – difficult because one of the players, the janitor Kobyella, is wounded and dies in the course of it, and has to be propped up against baskets full of blood-stained letters to prevent him showing his hand. At the end of the battle, Bronski is executed with 30 other Poles, ‘in the courtyard of the post-office, with arms upraised and hands folded behind their necks ... they were thirsty and having their pictures taken for the newsreels ... In Jan Bronski’s upraised hand he held a few skat cards and with one hand holding the queen of hearts, I think, he waved to Oskar, his departing son.’ At the graveside of Matzerath, his other father, in 1945, Oskar wills himself to grow again, ready to assume the responsibilities of an adult, but after another three years, in the course of which he has merely succeeded in growing a hump, he decides (shades of Uncle Toby) that the sickbed in the asylum is the only safe haven and worthwhile goal, after all.

A child with an adult mind, a freak that combines the insights, feelings and sexuality of an adult with the guile and the scotfree licence of a child, Oskar has only two means of making an impact on the adult world: one is his drum, or rather series of drums, made of tin, the sides painted with red and white triangles, the colours of the Polish Army. (The present writer recollects a string of grey stallions of the Polish cavalry, a couple of tall red-and-white drums slung from each, parading on a brilliant Sunday morning in August 1939 along the cobbled street of a little town in Polish Silesia, less than thirty miles away from the German frontier, less than three weeks away from their doom.) The tin drum is the instrument of Oskar’s art and self-expression, his defence – with it, he can disrupt political meetings and entertain Wehrmacht audiences – and the means of his brief flights of freedom: all-powerful and compelling at one moment, useless in competing even with the noise of carpet-beating the next, an instrument of pure, disinterested l’art-pour-l’art at one point, a source of cheap and meretricious entertainment at another.

In the course of defending his drum from seizure by his exasperated family, Oskar discovers a second defence: his capacity to aim his voice at any glass area that is visible to him and to sing it to bits. And this talent, too, is used ambivalently, now as the desperate protest of a child that is being unspeakably maltreated by other children, now as a manifestation of aesthetic decadence and manneristic art: during his stay in German-occupied Paris, Oskar devises an art-historical scheme following which he systematically destroys the contents of an exhibition covering the history of glass from Louis XIV to Art Nouveau. The identifications of author with hero are as grotesque – and as outrageously explicit – as all the other ploys.

There are a good many story-lines one might follow through the novel, but a better way of conveying its extraordinary achievement, and the formal difficulties that lie in the way of that achievement, is to concentrate on a single episode. Before doing that, though, the most obvious objection to the novel (and indeed to The Dog Years too) must be faced.

The reader may have gained the impression that here is a fictional monster – or a monster fiction – of six or seven hundred pages where anything goes – heedless fantasy let loose on unresistant material, with no discernible unifying meaning or coherence of any kind. Or else he may suspect that, German fictions being notorious for their highflown metaphysical messages, the critic will now pull the rabbit out of the hat and demonstrate the transcendental meaning of it all.

There is (as far as I can see) no such transcendental meaning or message, and yet the novel is much more than a series of self-indulgent or author-indulgent images and random episodes. Its meaning is to be wrested from its compositional difficulties, and they in turn may best be approached from the perspective of another great favourite of Grass’s, Melville’s Moby Dick. In the very deeps of that other monster creation you may stumble across a rumination in which the narrator anticipates the charge of self-indulgence and of excessive preoccupation with the customs and the bits and pieces of the whaling craft: ‘So ignorant are most landsmen of some of the plainest and most palpable wonders of the world, that without some hints [!] touching the plain facts, historical or otherwise, of the fishery, they might scout at Moby-Dick as a monstrous fable, or still worse and more detestable, a hideous and intolerable allegory.’ Grass is in a similar predicament. The story he is writing is deeply, irreversibly steeped in the history of its time – or rather, not in that history, but in the crude and gory facts of the past from which such a history will have to be fashioned. These facts are notorious for offering the utmost resistance to interpretation of whatever kind. This is both the experience of readers of a different generation or culture and the understanding which Grass himself has of his national past and which he shares with his own generation of readers. Yet his impulse to write a historical fiction is clearly every bit as strong as the impulse to understand and come honourably to terms with that impossible past: in the creative act the two are to be united.

The work, therefore, is threatened by two difficulties. On the one hand, there is the danger of creating a sequence in which one ‘monstrous fable’ follows another and the whole ends up as little more than a series of metaphors gone wild. The other, ‘still worse and more detestable’, is that the impossible past gets swallowed up by ‘a hideous and intolerable allegory’.

Again and again, we are likely to return to the question: can the unspeakable obscenity that called itself the Third Reich be fictionalised at all? Clearly, such an undertaking will require a certain imaginative freedom from the past – a freedom which was not available to Thomas Mann and his contemporaries, and which many critics may not be willing to grant. Yet ‘unspeakable’ is itself a descriptive adjective and a legitimate part of the critic’s vocabulary; and it is one thing to say (as some critics have said) that the novel cannot be interpreted, that it is incapable of yielding a meaning, and another to say that its meaning is hedged in with meaninglessness, with the grave difficulty of making sense of apparently senseless horror. True, we cannot interpret the story that is told in its fantastic episodes in simple, unambiguous terms, but this isn’t due to some degeneracy of its author’s sensibilities (as was predictably claimed by its indignant right-wing critics), but, on the contrary, to the immense difficulty he is bound to face when devising the underlying strategy of his novel. For what it aims to convey is the paradox that the daily practice and horrors of the Third Reich went on side by side with the daily practice and horrors of the ordinary world; that these things were and are and always have been a part of the human situation; and that this knowledge – I mean that monstrosities are human and that humankind is monstrous – must be grasped to the full, undiminished by the lethargy that comes from repetition and familiarity, yet without allowing it to destroy both the feeling of outrage and the capacity for interpretation, the capacity for giving a fictional account of it all. What Grass’s novel in its own blasphemous way aims to convey is the paradox (whose supreme illustration is the death of Christ) that everything is ordinary and everything is special.

The two dangers that beset the work may now be restated: it is threatened either by a trivialisation of its material or by a demonisation of it. On the one hand, there is the risk that the metaphors, set out to convey the terrible, ‘unspeakable’ evil, will turn out to be of an intolerable obscurity, incomprehensibly transcending all mundane experience – which is what, in The Dog Years, Grass satirises in the oracular utterances of Martin Heidegger. And there is the opposite risk – of the story slopping over into a mood of ghastly tolerance, a mood in which we are asked to accept every infamy as part of the human condition, for no better reason than that (as the great Hegel observed in one of his less great moments) in the night all cows are black, boys will be boys, men will be men and that’s how it’s always been. These are the two dangers attending Grass’s prose when things go wrong. They are reflected in his readers’ reactions – a sudden switching over from blank incomprehension to bored déjà vu.

But of course, at its best – as in ‘Faith, Hope and Love’, the last chapter of the first book of The Tin Drum – the narrative emerges from those twin dangers with supreme success. The heading from the First Epistle to the Corinthians provides the chapter with its leitmotif. It begins in fairytale fashion, with a phrase that will be repeated throughout the chapter: ‘There was once a musician: his name was Meyn and he played the trumpet too beautifully for words.’ Meyn has been a friend of Oskar’s, and of Oskar’s friend Herbert, at whose funeral he blows the trumpet, as always when he is drunk, too beautifully for words. But Meyn is also a Storm Trooper, a member of the SA, a psychotic who, when sober and deeply disturbed, tries to kill his four cats and bury them in his garbage can, but ‘because the cats weren’t all-the-way dead, they gave him away’. And so the man Meyn was expelled from the party ‘for inhuman cruelty to animals’ and ‘conduct unbecoming to a Storm Trooper’, even though ‘on the night of November 8th [1938], which later became known as Crystal Night, he helped set fire to the Langfuhr Synagogue in Michaelisweg. Even his meritorious activity the following morning, when a number of stores, carefully designated in advance, were closed down for the good of the nation’, could not halt his expulsion from the Mounted SA. Later, Meyn joins the SS.

This 8th of November is also the day when Oskar goes to visit his friend and chief supplier of red-and-white tin drums, the toyshop owner Sigismund Markus. He finds the shop full of SA men, in uniforms like Meyn’s, but ‘Meyn was not there; just as the ones who were there were not somewhere else’ (this is the phraseology of post-war alibis). The shop is full of excrements (this connects with a lengthy disquisition on the colour of brown, which is also the colour of the party) and:

The toy merchant sat behind his desk. As usual he had on sleeve protectors over his dark-grey everyday jacket. Dandruff on his shoulders showed that his scalp was in bad shape. One of the SA men with puppets on his fingers poked him with Kasperl’s wooden grandmother, but Markus was beyond being spoken to, beyond being hurt or humiliated. Before him on the desk stood an empty water glass; the sound of his crashing shopwindow had made him thirsty no doubt.

The detail of the dandruff is no more grotesque than the spectacle of the men letting down their trousers or the picture of the dead man.

Oskar leaves the shop, and, outside, ‘some pious ladies and strikingly ugly girls’ were handing out religious tracts under a banner with an inscription from the 13th Chapter of the First Epistle to the Corinthians: ‘Faith, hope, love,’ Oskar read and played with the three words as a juggler plays with bottles:

Leichtgläubig, Hoffmannstropfen, Liebesperlen, Gutehoffnungshütte, Liebfrauenmilch, Gläubigerversammlung, Glaubst du, dass es morgen regnen wird? Ein ganzes leichtgläubiges Volk glaubte an den Weihnachtsmann. Aber der Weihnachtsmann war in Wirklichkeit der Gasmann, Ich glaube, dass es nach Nüssen riecht und nach Mandeln ...

The sequence is by definition untranslatable, but this is how the punning on the three saintly virtues ends:

‘Faith ... hope ... love,’ Oskar read: faith healer, Old Faithful, faithless hope, hope chest, Cape of Good Hope, hopeless love, Love’s Labour’s Lost, six love. An entire credulous nation believed, there’s faith for you, in Santa Claus. But Santa Claus was really the gasman. I believe – such is my faith – that it smells of walnuts and almonds. But it smelled of gas. Soon, so they said, ’t will be the first Sunday of Advent. And the first, second, third, and fourth Sundays of Advent were turned on like gas cocks, to produce a credible smell of walnuts and almonds, so that all those who liked to crack nuts could take comfort and believe:

He’s coming, he’s coming. Who is coming? The Christ child, the Saviour? Or is it the heavenly gasman with the gas meter under his arm, that always goes ticktock? And he said: I am the Saviour of this world, without me you can’t cook. And he was not too demanding, he offered special rates, turned on the freshly polished gas cocks, and let the Holy Ghost pour forth, so the dove, or squab, might be cooked. And handed out walnuts and almonds which were promptly cracked, and they too poured forth spirit and gas.

This is the horrendous side by side with, but undiminished by, the practices of the ordinary world.

‘Ask my pen,’ says Tristram Shandy, when questioned about the design of his strange book: ‘Ask my pen; it governs me; I govern not it.’ What is being undertaken in Grass’s equally strange book is something very new but also, going back to Laurence Sterne, very old. However different the mood of the two novels, they both disdain narrative order and live by extravagant metaphor.

We are accustomed to think of word games, situational games, and the detailed working out of bizarre images, as the conceits of humorous novels. But they are not necessarily and exclusively so. Tristram Shandy is certainly a humorous novel, but so, in parts, is The Tin Drum; where the humour of the one shades off into sentimentality, the other veers into tragi-comedy; and where Tristram Shandy is concerned to guy and illustrate causal propositions and absurd inferences from Locke’s philosophy, The Tin Drum guys causality and replaces it by verbal association. Its humour and its seriousness are not polarised in some inhuman Hegelian dialectic: they are made continuous with each other, as the everyday and the monstrous are continuous in our experience.

Our conventional terminology, which moves within the squirrel cage of symbols and allegories, won’t quite do. Oskar isn’t the symbol of anything, just as Uncle Toby or Corporal Trim aren’t the symbols of anything. Oskar is what he is, a freak, because freaks alone (according to the logic the author compels us to accept) can be brought into some sort of meaningful relationship with this world – and that relationship is one of metaphors, puns, and of the logic that is built from metaphors and puns. The word-game on faith-hope-love, on the Spirit (pneuma) and gas, Santa Claus and the holy gasman, may suggest elements of satire (German love of Christmas, the Church’s comforting concern for the spirit of everyone except those who were gassed, Hitler’s role as self-appointed Saviour, etc), but the satirical element is subsidiary to the main undertaking of the novel, which is to match an almost unbelievable, in explicable past with almost unbelievable and inexplicable metaphors, and thus to make it believable and explain it without reducing its tragic pathos and without explaining it away. And it is an added grace that all this is done without succumbing to that ghastly tendency (so characteristic of post-Nietzschean Germany) to justify and vindicate everything by adverting to a ‘tragic view of life’.

There are traces and analogies of a Christian concern in the novel. At their most obvious, these traces are to be seen in the negative religiousness of blasphemy, such as the exegesis of ‘Faith, Hope and Love’, or the repeated scenes of Oskar Matzerath’s imitation of the Christ Child. It is as if blasphemy were the only form of social religiousness available to blasphemous times. But there are also analogies pointing to a religious meaning. The precarious stylistic balance I mentioned, between the obscurity of demonisation and the triviality of ‘all’s grist to the human mill,’ involving a full acknowledgement of the horrors of the past which the creative conscience prevents from turning either into complacent tolerance or annihilating despair – this balance is surely seen at its clearest within such a framework as is provided by St Augustine’s exhortation, often quoted ‘with particular relish and sadness’, as Christopher Ricks observes in his introduction to Tristram Shandy, by Samuel Beckett: ‘Do not despair, one of the thieves was saved; do not presume, one of the thieves was damned.’ If, in post-war literature, other literary ways were devised of coming to terms with the past, without presumption and without despair, I have failed to notice them. So far, Grass’s achievement is unique.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.