At his final White House Correspondents’ dinner, Barack Obama joked that he had been grizzled by the presidency while Michelle had barely aged a day. ‘She looks so happy to be here … That’s called practice. It’s like learning to do three-minute planks.’ Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama speaks to the effort of looking relaxed in the public eye, not least because, of all Sherald’s paintings currently on display at the Whitney survey of her work (until 10 August), it’s the only one behind glass and the only one with its own room and security guard. Sherald usually gives her works enigmatic titles – Well Prepared and Maladjusted; The Lesson of Falling Leaves – but here we have simply Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, three generations distilled into one persona.

Sherald was commissioned to paint the portrait in 2017, after the end of Obama’s second term. It was an intriguing choice at the time. She was in her early forties, had only recently been able to give up her job as a waitress and was barely known to the art world. Her painting career had been stalled by the need to care for ailing relatives and her own diagnosis of congestive heart failure (it isn’t often you see an organ donor thanked in a catalogue). Michelle’s husband, by contrast, picked for his portrait the artist Kehinde Wiley, who had already been the subject of a retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum and whose work had sold to institutions including the Met.

Sherald’s star had begun to rise after she won the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition at the Smithsonian in 2016. The prize painting, Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), is displayed in an early room at the Whitney and it gives a sense of why she might have had an edge over more established artists for the presidential commission. It shows a young woman, perhaps only a girl, wearing a polka-dot shift dress, white gloves and a red pillbox hat. She holds an oversized tea cup and saucer, lending a note of whimsy to the painting, but everything else suggests furious restraint. Sherald portrays her sitters with a particular tautness. She also has a feeling for vivid colour. Miss Everything is a vision in vermilion and turquoise. Sherald pays meticulous attention to the seams of her gloves and the pompom on her hat, but the girl’s skin is painted with shades of grey in what has become the artist’s signature technique: rendering Black skin as grisaille in order to make us think again about notions of colour and race. Like most of Sherald’s figures, Miss Everything casts an appraising look at the viewer. The overall effect is one of graphic self-possession.

Sherald almost always paints Black subjects, most of whom are strangers she approaches in the street. Together, they select an outfit from the sitter’s clothes (this is another key aspect of her work: her lively interest in the ways we fashion ourselves). Long before she was commissioned to paint a celebrity, Sherald understood that anyone who feels scrutinised in public is likely to use appearance as a kind of armour. After the clothes comes a photography session, which produces the source material for the painting – an image already shaped by hours of posing for the camera (it isn’t surprising that her portraits often feature on magazine covers).

In earlier paintings, Sherald experimented with a looser style. Her vibrant backgrounds, speckled with splashes of turpentine, recall marble, foliage or animal print. Charcoal marks show the ghostly presence of preliminary sketches: where a finger was once positioned, the first wisps of hair. The man in The Rabbit in the Hat (2009) has a softness to his frown, and to his striped lime-green jacket, that contrasts with the sharply focused depiction of the rabbit. The vagueness of the figures in some of these early paintings can make our attention shift out of focus too.

Sherald’s early works are weighed down by her artistic affiliations: Barkley Hendricks with the dressing-up box of René Magritte. A woman in jodhpurs and a big-bowed blouse holds a unicorn hobby horse; a man in a bowler hat levitates a model ship over his palm. Their stiffness comes from forcing an idea onto an image rather than allowing the conceit to come through. The distinction between taut and wooden can be very fine. But when Sherald hits her stride, the results are compelling. Her more recent works have a winning clarity of composition: a single figure, thrown against a coloured background, and realised in such a way as to make us ask what it costs to present oneself with this degree of polish.

On entering the exhibition, the viewer immediately encounters a curved wall on which are hung five of Sherald’s most striking paintings, all the same size and placed unusually low: Sherald says she wants visitors to meet her subjects’ gaze. Every detail bristles with life: the fine halo of soft black fur against the salmon pink background in Mama Has Made the Bread (How Things Are Measured), the woven gold of the straw hat in Mother and Child – details that testify to Sherald’s fluency with her materials.

Alice Neel liked to say that she painted all of a person: ‘What the world has done to them and their retaliation’. The opposite might be said of Sherald: she seems less concerned with the bruised interior than with the exterior shell we create under duress. When Ta-Nehisi Coates edited an issue of Vanity Fair in September 2020, he commissioned Sherald to make a cover painting of Breonna Taylor, who had been killed by police earlier that year. Sherald worked with Taylor’s family to create an idealised portrait, a painting of her subject in the future conditional. This is Taylor the way she might have been and would have liked to have been seen, dressed to impress in shades of Tiffany turquoise with fabulous hair and an engagement ring that may have been on its way.

The risk with this sort of work is that it can start to feel formulaic, and perhaps this is why Sherald has begun to expand her range of poses and settings. In A Midsummer Afternoon Dream (2020), a woman leans against the handlebars of her pale yellow bicycle, no longer set against a plain background but in some suburban idyll. The uprights of a white picket fence are echoed in the field of sunflowers beyond; some of the flowers have been gathered into a bouquet, which sits in the woman’s bicycle basket alongside a small white dog. It’s a saccharine dream, and that’s surely the point, but in complicating the composition Sherald sacrifices the human interest that accompanied her previous simplicity.

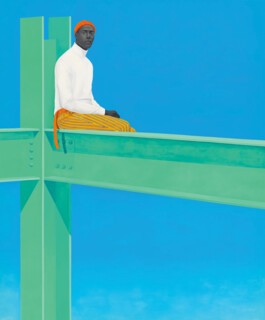

More successful has been the leap in scale Sherald has made in recent years (no doubt encouraged by Hauser & Wirth, the gallery to which she moved in 2018). One of the works in a later room at the Whitney is more than three metres in height and depicts a man perched high on steel girders. The verdigris metalwork nods to Manet’s use of a similar framing device in The Balcony, though here it accents a single figure, dressed somewhere between construction worker and clown in vivid orange beanie hat and striped yellow trousers. Sherald worked from an old photograph of construction workers on a New York skyscraper, but the man’s dandyish insouciance gives the image a sense of unreality and suspenseful calm.

When the official portraits of the Obamas were unveiled in 2018, Sherald was criticised by some for making a painting that didn’t capture the version of ‘Michelle’ people thought they knew. I suspect one ingredient was missing: her electric smile. Obama sits in a floor-length gown, legs crossed, her head resting on one hand, her expression sombre. She might be bored, defiant, curious, concerned, resigned: Sherald doesn’t offer us any clues, but she captures celebrity’s peculiar combination of intimacy and inscrutability.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.