In 1940, James Baldwin visited the painter Beauford Delaney at his studio on Greene Street. Baldwin was fifteen and a high school student; the meeting had been arranged by a friend. ‘Beauford was the first living, walking proof, for me, that a Black man could be an artist,’ Baldwin wrote later. In Delaney, a gay black artist from Knoxville, 23 years his senior and living downtown, rather than in Harlem, Baldwin saw a possible future for himself. They became close friends; Baldwin would go on to sit for half a dozen portraits.

A decade after their first meeting, Baldwin wrote to Delaney, who was suffering from depression and alcoholism, urging him to move to Paris, as Baldwin had done a few years earlier. Delaney arrived in 1953, on a plane ticket bought by a wealthy friend. Two years later, he moved to a flat in Clamart, a suburb outside Paris, the city where he remained until his death in 1979.

Delaney’s demons followed him to Paris; nonetheless, he experienced an unprecedented sense of freedom in his new home. Best known as a portraitist, he began to make fully abstract paintings and injected his figurative paintings with delirious colour. Baldwin spent the autumn of 1955 with Delaney in Clamart, where he noted the influence of the place on Delaney’s style: ‘That life, that light, that miracle, are what I began to see in Beauford’s paintings.’

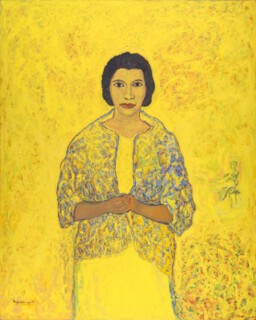

That ‘light, that miracle’ is on glorious display in Delaney’s portrait of the contralto Marian Anderson at Paris Noir, an exhibition at the Pompidou featuring the work of black artists living in Paris after the Second World War (until 30 June). In this enormous canvas, 162.4 by 130.3 cm, Anderson stands facing the viewer: a statuesque figure, eyes wide open, red lips sealed. Her hands are clasped in front of her, as though she were just about to open her mouth and sing. The backdrop, a radiant yellow that colours her dress and shawl, is grazed by streaks of orange, green and blue. It is sparsely sketched, save for the lower right-hand corner, where a thicket of marks appears just below the small, faintly drawn figure of a pianist. The richness of the impasto, the range of colour, seem to evoke the luminosity of Anderson’s voice.

The painting was made in 1965, when Anderson was 68 years old. The first black singer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera House, she was also a committed activist, celebrated for her involvement in the civil rights struggle. In 1939, the racist Daughters of the American Revolution had prevented her from singing to an integrated audience at Constitution Hall in Washington DC. Thanks to Eleanor Roosevelt, she performed instead for an audience of 75,000 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Two years before she sat for Delaney, she sang at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Portrayed face on, in the style of a Byzantine icon, Anderson is an imposing presence. But the background is equally striking, a colour field painting reminiscent of Delaney’s untitled 1962 abstraction, swirling with yellow paint, also on display at the Pompidou. Baldwin said that he first ‘learned about light from Beauford Delaney, the light contained in every thing, in every surface, in every face’, and the subject of Marian Anderson is light as much as Anderson herself – yellow light in particular. According to Delaney, yellow was the colour of ‘transcendence and hope’.

Delaney wasn’t the only black artist of his generation who felt liberated by Paris. Baldwin noted that Richard Wright considered it a ‘city of refuge’. Even Baldwin, who developed a much more jaundiced view of France, admitted that he could never bring himself to hate the French, because they had left him alone. As Paris Noir underscores, the city served as both sanctuary and training ground for some of America’s most important post-war black visual artists, including Ed Clark, Sam Gilliam, Bob Thompson, Romare Bearden and Barbara Chase-Riboud – artists whose auction sales remained quite modest, until the George Floyd protests led previously indifferent collectors to ‘discover’ black modernism. Paris wasn’t without racism, of course. Chester Himes and his white girlfriend were kicked out of their hotel after white American guests complained about the presence of an interracial couple. But, as the novelist William Gardner Smith explains in a television interview exhibited in one of the first rooms of Paris Noir, ‘for us black people there is less racism in France.’

Gardner Smith was referring to black Americans like himself. As he knew, Algerians in Paris confronted intense racism and police violence (the subject of his 1963 novel The Stone Face, which wasn’t translated into French until 2021). The Paris Noir of African Americans, who were seen as Americans first, and only after as blacks, had little in common with the Paris Noir of Africans and West Indians, who had left France’s colonial empire to work and study in the metropole. When the Guadeloupean writer Maryse Condé visited Paris as a teenager, she found it ‘a sunless city, a prison of dry stones and a maze of metros and buses where people remarked on my person with a complete lack of consideration: “Isn’t she adorable, the little Negro girl?”’ To the French, ‘I was a surprise. The exception in a race whom the whites obstinately considered repulsive and barbarous.’

The African and Caribbean artists in Paris Noir took advantage of the city’s art schools, making work that fused the languages of European modernism with their ancestral traditions. But, unlike their American counterparts, they couldn’t avoid their oppressors. As Baldwin wrote in ‘Encounter on the Seine: Black Meets Brown’, the ‘bitterness’ of the African in Paris was ‘unlike that of his American kinsman’, because ‘the African Negro’s status, conspicuous and subtly inconvenient, is that of a colonial; and he leads here the intangibly precarious life of someone abruptly and recently uprooted.’ It was precisely that shared sense of uprootedness that inspired the Francophone movement of black consciousness known as Négritude. Négritude is usually understood as a poetic movement, but Paris Noir makes the case for its impact on artists such as the Côte d’Ivoirian Aboudramane Doumbouya, whose sculpture The Fetish Priest’s Fort (1993), a totem-like object made of cardboard, wood, earth, hair and animal horn, is among the most striking pieces in the exhibition.

The work of American artists in Paris Noir seems, at first, quite distant from Doumbouya’s séance with the ancestors, or the work of Haitian artists such as Luce Turnier, whose extraordinary collage Cabane de Chantier (1970) suggests a graphic analogue of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Anarchitecture, or the Martinican Henri Guédon, represented here by K.K.K. (1979-83), an Art Brut painting of a naked black woman cornered by men in white hoods. In Ed Clark’s pink-and-blue abstractions and Delaney’s delicately homoerotic portraits of friends and lovers there is a sense of composure, of art made in conditions of relative freedom; the ‘struggle’ invoked by Thompson in the title of his 1963 painting is the battle for civil rights in the US, not one unfolding in France.

The great scope of Paris Noir makes it an exhilarating exhibition. But can these artworks really be considered expressions of a single Paris Noir, comprising, as the curators claim, a ‘counter-culture of modernity’? The arguments behind the show seem tinged with nostalgia for an era in which Paris was the home of radical styles of will. And yet they remind us that living and making work in Paris forced a great number of artists in the second half of the 20th century to reflect on what it meant to be black, and what it meant to be modern, at a time when the white art establishment treated black modernism as an oxymoron, or ignored it altogether. They may not have inhabited the same Paris Noir, but they shared a sense that their work had an inescapably public dimension. The woman depicted in Delaney’s Marian Anderson knows that her every move is politically consequential. Her lips may be closed, her hands clasped in anticipation, but she’s getting ready to raise her voice.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.