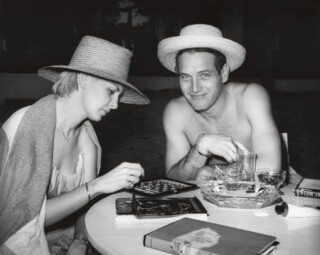

‘Thank you for keeping still,’ Elizabeth Taylor says to Paul Newman at the end of the movie version of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958). Taylor’s character is thanking Newman for not saying anything when he hears her lying about being pregnant. But ‘Thank you for keeping still’ is also a good summary of Newman’s acting style, especially in his early films, when the main thing required of him was that he display his magnificent torso and his dazzling blue eyes for the audience to drink in their full manly beauty. At the height of his stardom, long before he became a salad dressing entrepreneur, Newman’s screen presence was more that of a living statue than an actor: a Greek god with a suntan and a side parting. His handsomeness was made for posters and billboards. Many of his early performances – as a pool player in The Hustler in 1961, for example – look much more convincing and exciting in stills. The speaking Newman, though charismatic, gives very little of himself. There is often a vacancy to his acting, which can give the illusion of mystery. The producer John Foreman recalled that Newman’s second wife, Joanne Woodward, once said to him: ‘If you think he’s thinking something, he’s not always thinking something.’

In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Newman hardly moves his eyes when he speaks – only his mouth. We see him wearing dark grey pyjamas, standing with the help of crutches, sinking glass after glass of whiskey. Taylor and Newman are playing a married couple who have become estranged and are living in a dysfunctional household preoccupied with the impending death of its patriarch, Big Daddy. Newman is Brick Pollitt, a former athlete who has turned to drink to cope with his frustration at a broken ankle. Taylor – Maggie – spends the film trying to persuade him to sleep with her again. The screenplay censored the play’s reason for Brick’s failure to sleep with Maggie (he’s gay) and at the end of the film version, they fall into each other’s arms. Both Newman and Taylor were at the height of their starriness: here were the two most famous pairs of eyes in Hollywood, the violet of Taylor’s and the blue of Newman’s. Both of them were nominated for Oscars.

When he was well cast and well directed, Newman’s macho stillness could be mesmerising. The most obvious example is Cool Hand Luke (1967), a prison drama superbly directed by Stuart Rosenberg, whose background was in television, in which he plays a prisoner, beautiful and insouciant in denim, who refuses to submit to the demands of the authorities: ‘Just a lot of guys laying down a lot of rules and regulations’. Luke’s rebellion takes the form of a smirking and childish passivity. His nickname comes from winning a poker game through sheer bluff: ‘Sometimes, nothing can be a real cool hand.’ He earns the respect of his fellow inmates (including a young Dennis Hopper and Harry Dean Stanton) in a boxing match against another prisoner, Dragline (George Kennedy), through his dogged willingness to offer up his body as a punchbag. It’s one of Newman’s best performances and was forced out of him by Rosenberg, who realised he had to ‘disturb him a little’. In one scene, he told him: ‘Shit, we’ve got a copyright problem, you have to reverse the first line and the second line.’ Newman was angry, and replied: ‘For Chrissake, after all that fucking effort.’ Rosenberg then rolled the camera, ‘and he starts and it’s fucking brilliant.’ As the narrative plays out, Newman’s character becomes a secular Christ figure, often depicted bare-chested and supine (in this, it’s like The Hustler, where Newman keeps falling over, blind drunk from too much bourbon). In the film’s weirdest and most celebrated scene, Luke accepts a bet to eat fifty hardboiled eggs. By the end, he is lying semi-conscious as the other prisoners stuff the final few eggs into his mouth.

Staying still while looking handsome wasn’t a walk in the park. George Roy Hill, who directed Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, said he was so nervous on set that he always had three changes of shirt and plenty of deodorant to cope with his profuse sweating. There isn’t a hint of these nerves in his performance, which seems glib and dialled-in, for example in the scene where Butch takes the Katharine Ross character for a ride on his newfangled bicycle while ‘Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head’ plays on the soundtrack. Hill said that Newman would often delay the shooting of a scene because he wanted to discuss every element in detail (Robert Redford, who played the Sundance Kid, just wanted to hurry up and finish). ‘Then what Paul would do with the scene would have no relationship to what we’d been talking about for the last half-hour.’ He put far more agony and effort into his performances than the end result would suggest.

‘Who does one perform for? Who were you trying too hard to please? Mommy, Mommy – that kind of problem,’ Newman says in The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man, the posthumous memoir pieced together by the publisher and journalist David Rosenthal. His source material was a series of interviews Newman recorded with the screenwriter Stewart Stern between 1986 and 1991, along with ‘oral histories’ of Newman by his contemporaries. In her foreword, Newman’s daughter Melissa says he wanted to create ‘an offering to the offspring’ as well as to set the record straight after decades of tabloid stories about his life. But there was so much material that they became overwhelmed, and Newman burned all the tapes, including his own. After his death in 2008, however, his family discovered that the transcripts remained – tens of thousands of pages of them. Rosenthal has done a deft job of winnowing them down to a book which does not feel overlong and has great thematic consistency. This is the story, as Newman saw it, of a man ‘detached from everything’ as the result of a childhood in which he was valued only for looking good. None of the book’s interviewees fully examines the extent to which this extreme detachment was the key to his persona and his success on screen (though it also limited him as a film actor). In The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson complains that the young Newman was more ‘mannered’ than Brando. ‘He seems to me an uneasy, self-regarding personality, as if handsomeness had left him guilty.’ The impression given by the memoir is that handsomeness caused him not guilt but shame. The prettier he was, the more he was the creature his narcissistic mother wanted him to be, which was something he both strived for and rejected.

On the first page of the introduction, Newman introduces himself as ‘a little boy who became a decoration for his mother, a decoration for her house, admired for his decorative nature’. The adult Newman was even more decorative. At the height of his late 1950s stardom, a poll in a popular women’s magazine suggested that his was the picture most women in America used ‘when they abused themselves’, as Newman put it. He clearly found it stifling and often distressing to be looked at with such intensity – and who can blame him? He recognised how much of his success he owed to his appearance, but also described it as a ‘plague’.

His mother, Teresa (‘Tress’) Fetzko, was immensely houseproud – she once bought a white Spitz dog because it would look good against the black of her new carpet – and unpredictable. Newman’s father, Arthur Newman Senior, ran Newman-Stern, the leading sporting goods store in Shaker Heights, Ohio, a Cleveland suburb Newman describes as ‘lily white’. The pair met when Tress was working at a cinema in Cleveland. She had grown up Catholic in Austro-Hungary; Arthur was Jewish – Paul said theirs was the only Jewish household on their street – and after their marriage, Tress converted to Christian Science as a kind of halfway house. Newman thought his mother saw him as ‘a weapon of her Catholicism to be paraded in front of my father’s people as the royal vindication of her own family, her smartness, her genes’. He told Stern that he preferred to see himself as Jewish because it was ‘harder’.

Stern describes Tress as ‘overwhelmingly proud’ of Paul’s looks. She would ‘attack him savagely with a hairbrush then smother him with love’. Paul and his older brother, Art, would go into the dining room and bang their heads against the wall until they made a hole so big their parents noticed. Art was not quite as beautiful as Paul, though he did have the same blue eyes, and in a racing car movie called Winning was used as an eye stand-in for his brother (he was working as a production manager on the film). Much of the time, Paul would conform and be the family ornament. ‘As a child, I might do something cute or come downstairs looking especially pretty, wearing little shirts and a sweater, and [my mother] revelled in the great flood of emotion that flowed through her, whether it was tears or joy. The child himself was not really seen.’ This was distressing, but it was also highly effective training for a life in Hollywood.

Newman describes his mother as ‘the most suspicious woman who ever lived, hysterical with the thought she’d never be accepted or get her fair share of anything’. One of Paul’s schoolfriends told Stern that when he came round after school, Tress would often have baked a big strawberry cake. But he also recalled that there was something ‘sad’ about the tidiness of the house. There were sheets covering all of the furniture in the living room to keep it clean: ‘It didn’t feel like anybody lived there.’ When, many years later, Newman’s son Scott got trapped in one of the upstairs bathrooms, Tress refused to allow Newman to break down the door to rescue him (he eventually called the fire department). Newman’s father drank, turning to liquor to take ‘the edge off before dinner’. If Tress was smothering in her love, Arthur was ‘dismissive, disinterested’, a constant note of sarcasm in his voice. Newman felt that because he never excelled at school, ‘I never gave my father anything to be proud of.’ The only thing that gained his father’s approval was making money. From the age of thirteen, he had a series of different jobs: ‘making deliveries for the florist and the dry cleaner, carting pickle barrels and Coca-Cola cases up and down stairs for the delicatessen’ and selling brooms door to door.

After a spell in the Navy during the war, he enrolled in Kenyon College where he found it hard to keep up with the work (although he broke ‘the school’s beer-chugalug record’). A classmate told Stern that even in the hard drinking culture of the school, Newman was famous, and would ‘run around stark naked, sloshed out of his mind’. He fell into the theatre but said that ‘I never enjoyed acting, never enjoyed going out there and doing it.’

But acting was better than staying at home, running his father’s sporting goods store. His father died in 1950, aged 56, only a year after Newman graduated from college. Paul was living at home with his first wife, Jackie, a college student who also wanted to act. They waited until their wedding night to have sex and Newman thought that their first child, Scott, might have been conceived that night. In her interview with Stern, Jackie said that Paul was ‘very, very upset by his father’s death’ and didn’t want to work in the family firm, but probably did it because of ‘pressure from Tress and guilt’. He was developing a new ‘plan in life’, however: to go to Yale School of Drama. He sent in the application without even discussing it with Jackie.

It didn’t take long for him to become spectacularly successful. In 1953, he starred on Broadway in William Inge’s Picnic, in which he was ‘stiff and wooden but an actor’, according to the film director Sidney Lumet. John Foreman told Stern that every studio wanted him after that, and he officially became the ‘hot guy’. Over the next few years he just got hotter and hotter, probably helped, as he himself acknowledged, by the death of James Dean in 1955. Dean had been slated to play the middleweight boxer Rocky Graziano in Somebody Up There Likes Me; Newman was asked to replace him.

‘By now, I’d become something of a movie star,’ Newman said of the success of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Following that performance, he was given the chance to act on Broadway in a new Tennessee Williams play directed by Elia Kazan, Sweet Bird of Youth. Newman played Chance Wayne, a gigolo ‘who’s attached himself to an ageing, alcoholic actress, the Princess’. In one scene, Chance has a soliloquy in which he expresses grief at seeing the love of his life for the last time. The speech worried Newman. ‘I wondered: how does a person who is anaesthetised in real life tap a core of emotion that would be available for someone else to feel?’ His solution was to stare at a light at the back of the auditorium to make him tear up. One day, the light was gone. Kazan had got wise to his trick. ‘I was so enraged that I actually wept with frustration.’ Kazan later told Stern that he found Newman good but not exceptional as an actor. ‘There’s something in him that’s masked, but underneath it, there’s a soul that wants to do many things.’

This changed after he fell in love with Joanne Woodward. He told Stern that ‘Joanne gave birth to a sexual creature.’ When he was studying at the Actors Studio in New York, Ben Gazzara criticised Newman’s stage anger, calling it ‘phony … just yelling’. After Woodward’s arrival, he felt able to tap into a more convincing range of emotions. They met in New York at the office of their mutual agent, Maynard Morris. Woodward later said that he looked as though he’d been ‘kept on ice’ and she hated him on sight. But then they were both cast as understudies in Picnic (before Newman was promoted to the lead) and each night in the wings she would try to teach him how to do a sexy dance, mimicking the actors on stage, until Newman realised that he had ‘this terrible problem in my pants’. For several years, he vacillated between his marriage and his affair, leaving, he said, ‘a trail of lust all over the place’. Eventually, he divorced Jackie, with whom he now had three children, and married Joanne, with whom he would have another three. Stephanie, his third child with Jackie, described it as ‘an unbearable story … She was left with three kids under the age of five … she wanted to be an actress and she had to watch my father and stepmother ride off into the sunset with Hollywood contracts.’

The remarkably long-lived union – both professional and romantic – between Woodward and Newman is the main theme of the second big project to be generated from the Stern transcripts. The Last Movie Stars is a six-part documentary directed by the actor Ethan Hawke – a Newman fanboy who fell in love with cinema after watching Butch Cassidy. It moves beyond individual biography to become an extended riff on the differences between art and stardom and the wonders and horrors of extreme fame. Filmed at the height of the Covid lockdowns, Hawke got a series of Hollywood A-listers to perform the parts of Newman, Woodward and the other voices in the transcripts via Zoom. George Clooney takes the part of Newman. Laura Linney plays Woodward, which is appropriate since she was mentored by Woodward as a young actor. Zoe Kazan, the granddaughter of Elia, plays Jackie McDonald. Brooks Ashmanskas, who is mostly known for his theatre acting, gives a pleasingly fruity rendition of Gore Vidal – one of the couple’s closest friends – and speaks the lines that give the documentary its title. Vidal observed that Woodward and Newman ‘presided over the end of the movies as the universal art form. Movies have now been taken over by television … people will think of them as the last movie stars … the last people who were treated at the beginning of their careers the way Gary Cooper, Katharine Hepburn were treated. And they survived.’

Vidal’s pronouncement now feels pretty shaky. It’s true that the dominance of two-hour pictures on the big screen has been steadily supplanted by ever smaller screens showing film in ever smaller fragments, from TV to laptops to phones. But it’s hard to argue that Newman and Woodward were ‘the last movie stars’ at a moment when the 60-year-old Tom Cruise has just had the first $100 million opening of his career, for Top Gun: Maverick, in which he not only acted but performed many of the most dangerous stunts. How would you describe Tom Cruise (or Will Smith or Johnny Depp) except as a movie star? When asked why he did his own stunts, Cruise said: ‘No one asked Gene Kelly, “Why do you dance?”’ It seems fitting that Cruise’s first serious – as opposed to commercial – role was in The Colour of Money (1986), playing opposite Newman in Martin Scorsese’s reprise of The Hustler, in which Cruise is the young pool-playing hustler and Newman the has-been attempting to reprise his own former glory. It’s a much better film than the original and Cruise’s performance is animated in all the ways that Newman’s was stagnant. Cruise does annoyingly perky victory dances, he holds a pool cue with great intensity, he gets angry, he grins like a maniac, he French kisses his beautiful girlfriend (played by Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), he argues with Newman and through it all seems fully committed to the part and what he can bring to it, even if his character is a jerk. In short, he was already fully the film star Tom Cruise, a figure who – unlike the young Newman – seems untroubled by his own handsomeness; then again, his handsomeness is so much less than Newman’s and perhaps easier to bear.

Another flaw in the ‘last movie stars’ notion is that not many people look back at the Newman-Woodward output. They made sixteen motion pictures together, culminating in the Merchant-Ivory film Mr and Mrs Bridge in 1990, but few of them have lasted. Who, now, watches The Long, Hot Summer, a clunking melodrama from 1958 notable only for a cameo by Orson Welles? They were no Bogart and Bacall: all of Newman’s most successful films – Cool Hand Luke, The Verdict, Hud, The Sting – were made without Woodward.

One of the documentary’s recurring themes is that although Woodward had more dramatic talent, Newman had the box-office success. As Hawke says at one point, ‘many of us lose our dreams. But most of us don’t have a partner who has exactly the same dreams, and his come true.’ Newman and Woodward are a lens through which to examine what separates a star from other actors. When you see them on screen together, she tends to be much better than him – if by better, we mean convincing in the role. This was the way the couple themselves saw it. Newman directed her in Rachel, Rachel, a 1968 film (scripted by Stern) in which she plays a lonely schoolteacher. Time magazine praised her ‘transcendent strength’: ‘There is no gesture too minor for her to master.’ Frank Corsaro, who also acted in the movie, remembered that, ‘as a director, Paul made very specific demands on the cast in areas of feeling and playfulness that often were missing in his own work as an actor.’

One of their daughters, Lissy, told Hawke that Woodward ‘knew that her husband, who was really famous, deeply believed that she was a better actor than he was’. But being a ‘better actor’ doesn’t always equate to being a movie star, someone whose smile or frown can do strange things to us as we sit watching them in the dark. Vidal said that Newman was like Gary Cooper or Henry Fonda: ‘They are so good no one knows they are any good.’ Consider A New Kind of Love, a deeply silly and frequently offensive rom-com from 1963. Newman plays a womanising journalist (Steve Sherman); Woodward is a fashion buyer (Samantha Blake) who has decided she wants nothing more to do with love. On a trip to Paris, she changes her mind and has a makeover so extreme that the Newman character mistakes her for a high-class prostitute and conducts a series of interviews with her to gain insights into the life of a call girl, while also – you don’t say – falling in love. In one of the more bizarre scenes, they go to a football match and Sherman fantasises about her being a goalkeeper in a gold lamé bikini, saving the ball with her gyrating hips before the whole team leap on top of her. Woodward does her valiant best, bringing a cool intelligence and humour to the role. She is fully present in every scene. And yet it is Newman who stays in the mind: Newman downing a beer at a bar; Newman adjusting his tie with a nonchalant arrogance; Newman grinning in a camel coat; Newman folding Woodward in his arms and kissing her. Is he convincing as hot-shot journalist Steve Sherman? It doesn’t really matter. He is Paul Newman. The director Stuart Rosenberg said that in 1967, there were only two stars in the world: Paul Newman and Steve McQueen.

Even though Newman achieved more than Tress could have ever dreamed of, it was never enough and never quite right. After he got together with Woodward, she invited Tress to the premiere of Ben-Hur along with Gore Vidal. A couple of years later, Tress came to visit Newman and Woodward in New York while he was performing on Broadway. He was in the car with his mother one evening when she said: ‘I know why your wife hates me! It’s because she is having an affair with Gore Vidal.’ Newman stopped the car and told her to get out. Woodward thought he should just have explained that her having an affair with Vidal was ‘manifestly impossible’. Newman didn’t speak to Tress for fifteen years after that. When his brother finally engineered a rapprochement, she came to see Newman and Woodward at their beach house in Malibu. On her arrival, she complimented them on their ‘wonderful house’. But within the first five minutes, according to Newman, she had reverted to type. ‘Are you working? Is the work good? How terrible it must be to be involved in a rotten industry that settles itself in violence and profanity and sex and gore. Oh, what you could have done if you only tried!’ They didn’t see much of each other until she became ill near the end of her life.

For both Newman and Woodward, the intensity of his stardom was an encumbrance. She felt like an ‘appendage’ and he felt diminished, as though all his work counted for nothing:

You work what you consider pretty hard at your craft and develop in a slow and painful way, and you’re getting to the point where you’re just starting to feel good about yourself – and not just the way you look – and then somebody says ‘Oh God, take off your sunglasses so I can see your baby blue eyes!’ All the self-esteem you’ve managed to build up goes right out the window. If I walked up to someone and said ‘Let me see your brassière,’ they’d be really offended.

Newman was aware, too, that his fame put unusual pressures on his children. He was a fond father and told the Guardian that his salad dressing business – which gives all of its profits to charity – grew out of cooking ‘supper every day for the children: hamburgers and grilled steak and soup, but always with a salad on the side’. In 1978, his oldest son, Scott, who worked as a stuntman and actor on some of his father’s films, died of an overdose at the age of 28, having suffered from alcoholism for several years. When asked by Stern what had gone wrong for Scott and whether there was anything he could have done to avert it, Newman said: ‘I’m not certain, but I don’t think I could have gone into films and been a movie star. I couldn’t have drunk.’

Drinking, Woodward told Stern, ‘used to be the anguish of our lives’ until Newman managed to cut it down and get by with a ‘tiny glass of wine’. He had a theory that his problems with alcohol had two origins: the fact that he drank so quickly and the fact that he wasn’t British. For many years, he said, he drank so fast that when he lay down to rest his body would gradually warm up the ice cold liquor inside him and ‘I’d actually be getting drunk and drunker as I dozed … My whole system was … based on catching up with all those ice cubes.’ He suggested that British people didn’t get as drunk as Americans because they didn’t put ice in their whiskey and took their beer warm. Tom Cruise told Stern that Newman’s relationship with alcohol was one of the ways in which he hurt himself. ‘He’ll torture himself by drinking a case of beer, then sit in the sauna for hours.’ Drinking to oblivion is a trait of many of the characters Newman played and it makes me feel deeply uneasy to watch him knock himself out with booze. Although the scripts may allude to some of the problems of alcohol abuse, there’s still a glamour in seeing that beautiful face downing a glass or a bottle. ‘Why can’t you lose your good looks, Brick?’ the Elizabeth Taylor character asks in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. ‘Most drinking men lose theirs, why can’t you?’

In the last two decades of his career, Newman finally looked older and lost a tiny bit of his handsome sheen. He seemed happier for it. In The Verdict, a 1982 legal drama directed by Sidney Lumet, Newman gave his best performance since Cool Hand Luke. ‘I don’t think I ever reached any comfortable emotional moment in any picture until I did The Verdict,’ he told Stern. Newman plays Frank Galvin, a cynical and alcoholic ambulance-chasing lawyer. Lumet rightly saw that in order to play drunk, you actually have to play someone who says ‘I’m not drunk, I’m sober,’ and he extracted from Newman a far more convincing and far less glamorous portrayal of a drinker than in his early films. Here, he sprays his mouth with breath freshener to take away the stench of alcohol and gulps eggs at his favourite bar to relieve his hangover. He acts with his whole face and his whole body and even when he’s just sitting glassy-eyed in a bar, he does it with more conviction than he did in the old days. Galvin has lost case after case when suddenly he finds himself representing a young woman in a coma after mistakes at a Catholic hospital. Representatives of the Church offer him a large amount of money to settle, but he is determined to take the case to trial. After the second week of rehearsals, Lumet took Newman to one side and told him it wasn’t working. Newman replied that the problem was the ‘fucking lines’. Lumet replied, ‘No, Paul. It isn’t the lines’ and said he needed to decide how much of himself he was going to ‘let us see’. According to Lumet, when Newman came in on Monday morning, he was a different actor, one who forced himself to do animation as well as stillness. It makes you wonder how much better he could have been in those early films if he had been directed as Lumet directed him. Robert Altman praised his performance in The Verdict for being brave enough for once to show us ‘his pink places’.

The question that agonises Newman in the memoir is that of authentic emotion, what he calls his ‘core’. He told Stern that for years no one else was real to him, not even Woodward and his children. He agonised over the difference between the interior and exterior person, and worried that ‘the light that people are looking at is not the same light that you think you are emanating.’ How strange it must have felt to be inside those blue eyes. He was the one person in the world who would never know the sheer thrill of catching sight of Paul Newman, the film star. ‘When we’ve been walking down a street,’ Stern said,

one of the things I’ve often said to Paul is how unfortunate it is that he won’t look back at people who are looking at him. I get a glow by the time we’ve gone two blocks, and find myself smiling simply because of the pleasure in people’s faces at seeing him. And it’s something Paul won’t see because he won’t look.

Listen to Bee Wilson discuss this piece on the LRB Podcast

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.