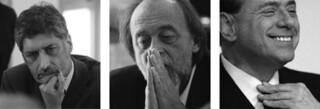

It was a hit and a miss for the Italian courts in October. On the one hand, in Milan, Silvio Berlusconi was convicted of tax fraud, sentenced to a year in jail, ordered to pay damages of €10 million and barred from public office for three years. The Economist, welcoming the verdict, looked back at Berlusconi’s entrance onto the political stage in 1994: ‘The footage of the dashing entrepreneur promising hope, renewal and good government now seems surreal.’ When didn’t it? On the other hand, in L’Aquila, six scientists and a former government official were found guilty of manslaughter because of what they said, or didn’t say, or were reported as saying, shortly before the earthquake that killed 309 people on 6 April 2009. They were each sentenced to six years in prison, ordered to pay damages of €7.8 million between them and all permanently barred from public office. An editorial in Nature put it succinctly: ‘the verdict is perverse and the sentence ludicrous.’ As in Berlusconi’s case, the verdict may yet be overturned: the defendants have two opportunities to appeal, and the sentences will only come into effect if and when both appeals have been rejected. The judge who found the seismologists guilty hasn’t yet published his reasoning – he gets three months to write it up – but a clear account of how they came to be in the dock in the first place appeared in Nature (No 477) just before the trial began last year.

In the months before the big one (magnitude 6.3), the area around L’Aquila was repeatedly shaken by smaller tremors. These ‘seismic swarms’ – 69 rumblings in January 2009, 78 in February, 100 in March – understandably had people worried. It didn’t help that Giampaolo Giuliani, a local retired lab technician and freelance seismic seer, was predicting a major shock based on his readings of radon levels. It appears that there may be a correlation between increased radon emissions and seismic activity, but there is as yet no scientific evidence that one can be used to predict the other. According to a report by the International Commission on Earthquake Forecasting, ‘at least two’ of Giuliani’s predictions (on 17 February and 30 March) were ‘false alarms’ and ‘no evidence examined by the commission indicates that he transmitted to the civil authorities a valid prediction of the mainshock before its occurrence.’ On 30 March, Giuliani says he was forbidden from making any more public pronouncements.

The next day, a special meeting of the Commissione Nazionale per la Previsione e Prevenzione dei Grandi Rischi was convened in L’Aquila (the commission usually met in Rome). ‘It is unlikely that an earthquake like the one in 1703’ – which obliterated the city – ‘could occur in the short term,’ Enzo Boschi, then head of the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV), is recorded as saying, ‘but the possibility cannot be totally excluded.’ It would be hard to find a geophysicist who’d find fault with that statement. Afterwards, however, Bernardo De Bernardinis, then deputy head of the Protezione Civile, told journalists that the situation was ‘absolutely normal’, there was ‘no danger’ and the seismic swarms in fact made a major earthquake less likely because of the ‘continuous discharge of energy’ – a claim without scientific foundation. Small earthquakes don’t mean that a big one is on the way, but they don’t mean that it isn’t, either. Boschi and De Bernardinis were two of the seven found guilty of manslaughter. Because of the official reassurances, the prosecution alleged, many people who would otherwise have left the city, or at least slept in their cars, were in bed when their houses collapsed around them.

One of the many problems with pointing the finger at the members of the commission is that it’s a distraction from the question of the collapsing buildings. It’s impossible to predict when earthquakes are going to happen, but very easy to say where, and the INGV’s detailed and freely available seismic hazard map of Italy does just that. L’Aquila has been hit by a high-magnitude quake three times in the last seven hundred years: it will happen again. And the best, perhaps the only way to reduce the death toll – other than by permanently abandoning the city, or for that matter a considerable swathe of the entire peninsula – is to construct earthquake-resistant buildings. ‘We get upset after every earthquake,’ Boschi said within hours of L’Aquila’s destruction, ‘but it’s not part of our culture to build in an adequate manner in seismic zones.’ Franco Barberi, another of the condemned scientists, said that ‘in California, an earthquake like this one would not have killed a single person.’

Berlusconi promised that a truly quake-proof town would be rebuilt on the ruins. Within a year, project CASE – which stands for Complessi Antisismici Sostenibili ed Ecocompatibili, but also means ‘houses’ – had thrown up 185 antiseismic, sustainable, ecocompatible blocks of flats to house thousands of the people made homeless by the earthquake. On 30 October, La Repubblica reported that at least two hundred of the seismic isolators (giant steel springs, essentially) supporting the buildings are substandard and liable to collapse if – or rather when – another high-magnitude quake strikes. It remains to be seen if anyone will be prosecuted.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.