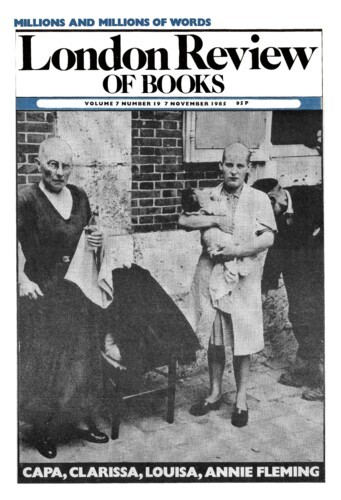

One of these books is very long and the other is very short. Each in its own way is a wonderful piece of work. They stand at opposite ends of the century that runs from the 1740s to the 1840s, but they may be thought to bear each other out, in ways which affect an understanding of the family life of that time, and of its incorporation in the literature of Romanticism – that part of it, in particular, which is premised on conceptions of the divided or multiple self and can be referred to as the literature of romantic duality. One of the books is fiction – of a kind, however, which is often investigated for its affinity to fact; while the other records the facts and feelings and constructions of the biographer of a friend. The first is the more than a million words of Samuel Richardson’s novel Clarissa, whose first edition has been issued by Penguin in the guise of a slab of gold bullion. The second is by an admirer of Richardson’s novels, two generations later – Lady Louisa Stuart, whose Memoire of Frances Scott, Lady Douglas as she became, has been redeemed from the archives of the Border nobility, with the blessing of a former prime minister, Lord Home. The memoir appears to have been written at some point in the 1820s, and is addressed to Frances’s daughter in order to acquaint her with certain passages in her mother’s early experience of an anxious family life. Frances died in 1817, the year before Scott’s novel Heart of Midlothian delivered its spectacle of an invincible female will. Louisa Stuart fancied that her friend Scott might have modelled his exemplary Jeanie Deans on her friend Frances. She seems to have been wrong: but it is never wrong to look for fact in fiction, and for fiction in fact.

The letters that compose Clarissa tell the story of an intelligent and beautiful girl who refuses a rich suitor and falls out with her ambitious and hideous family, the Harlowes. She is tricked into running away from her ‘friends’, as she calls them, by the rake Lovelace. This man gloats over the items of her dress on the day of her involuntary escape, items which indicate, what with the sharpness in the air, that she had not intended to be gone with him, for all that she had been drawn in that direction. He gloats over her ruffles, her mob-cap with its sky-blue ribbon, her apron of flowered lawn, her blue-satin braided shoes.

Her morning gown was a pale primrose-coloured paduasoy: the cuffs and robings curiously embroidered by the fingers of this ever charming Arachne in a running pattern of violets and their leaves; the light in the flowers silver; gold in the leaves. A pair of diamond snaps in her ears. A white handkerchief, wrought by the same inimitable fingers, concealed – Oh Belford! what still more inimitable beauties did it not conceal! – And I saw, all the way we rode, the bounding heart; by its throbbing motions I saw it! dancing beneath the charming umbrage.

Lovelace spirits this Primavera, or perhaps this Venus, to a London brothel, where he eventually drugs and rapes her. We had been brought to feel that she might have come to love him, in attempting to reform him, while Lovelace has acted from motives both of love and revenge – a teasing conspiratorial revenge which has intended harm to her, to the Harlowes, and to women. She is now in danger of the fate tersely ascribed to a girl in Louisa Stuart’s memoir: ‘She lost her character, married obscurely, and ceased to be talked of.’ Clarissa had been willing to be talked of as an old maid, which is how Louisa Stuart was to talk of herself. After the rape it is open to her to marry her attacker: but she refuses this orthodox course, to which she is encouraged by those around her, and chooses to die. She is a marriageable, marketable, impeccable Venus who has turned into a nun. She sleeps beside the coffin on which she has taken to writing her letters, and joyously awaits her heavenly reward.

These are some of the events and some of the emotions of Clarissa: a long story has been cut short, but it is a long story which has practically no digressions. Richardson’s reader Louisa Stuart would not have felt at sea in pondering such vicissitudes. She was the daughter of Lord Bute, another North British prime minister, whose retreat to Luton Hoo, in the sourness of political defeat, helped to embitter her youth. Her choice of a husband was cancelled by her father, and the friends she made outside the family circle were dearer to her than those friends who were her siblings. She had a gift for friendship, and for literature, which lasted for almost a century – she was born in 1757, ten years after the publication of the first two volumes of Clarissa. And those who have come to know her from a study of Scott’s life and works will not be startled by the quality of her memoir. Scott himself thought her the best literary critic he knew, thought she had genius, and a ‘perfect tact’. The memoir is critical of the romantic in a customary 18th-century fashion – a fashion that can be found in Scott. ‘Most people addicted to romancing are their own heroes.’ But it isn’t fanciful to suggest that she was to approach the door through which Scott was to pass, and which led to the invention and experience of a romantic literature, and that the vicissitudes of her life were such as to incite this approach. Nor is it fanciful to claim that her memoir is admirable in its sensitive astuteness. It is a work which is not discountenanced by the portrait of an afflicted and virtuous female, and of an adulterous aristocracy, which is conveyed in the celebrated novel by an earlier lady of quality, Madame de Lafayette’s La Princesse de Clèves.

Louisa Stuart’s memoir turns her friend Frances into a Clarissa-like victim and paragon – no one on earth like her. The theme of the persecuted maiden is treated – the theme which Richardson did much to transmit to the literature of Romanticism. Frances suffered the misfortune of incurring the enmity of her mother Lady Dalkeith, later Lady Greenwich, one of the unruly Campbell connection and a ‘wicked witch’, according to Louisa Stuart, herself a relative of the witch on her father’s side. There are commentators who have detected as implausible, in Richardson’s novel, not so much its postal dimension, the ‘ready scribbling’ which exceeds the call of duty and isn’t always fully compatible with decency – not that so much as the harshness of the Harlowes towards their paragon. But it would be a mistake to make light of the plausibility for the novel’s first readers, or for any readers, of this harshness. Lady Dalkeith was as harsh as any Harlowe. This passage depicts her in her ordinary abrasiveness, going about town: she ‘sallied every morning at the earliest visiting hour, entered the first house she found open, and there, in a voice rivalling the horn, published all the matches intrigues and divorces she had heard of; predicted as many more; descanted on the shameful behaviour of the women and the scandalous profligacy of the men; wondered what the world would come to – then bawled a little on public events, made war or peace; and, having emptied her whole budget, packed it afresh to carry it to another door, and another, and another, until dinner-time called her home. The rounds of the newspaper were not a bit more regular or certain.’ And Horace Walpole christened her the Morning Post, after a Private Eye of the time.

She took as her second husband the rogue politician Charles Townshend, who seems to have married her for money and influence, and to have gone in fear of her female will. According to J. Steven Watson’s Preface – one of two excellent introductory pieces, the other being by the editor of the volume – Townshend’s customs duties led to the loss of America, and his death in 1767 concluded a train of dazzling Parliamentary feats and turns. ‘Those volatile salts are evaporated,’ ran one of the tributes. Watson calls attention to the statement, in the biography of the politician by Namier and John Brooke, that Townshend needed his wit to shield a poverty of heart. This might be held to be like Lovelace, and in each case the wit is very brilliant. Each is a paragon in this respect. And Townshend was also known for his easy success with women. In 1767, Frances, the 17-year-old stepdaughter of this ‘young drunken epileptic’, in Watson’s words, witnessed the sudden end of a relationship with him which may have had the makings of a dangerous intimacy but may equally have rested on Townshend’s desire to shield her from her mother’s aversion. There is no evidence in the memoir of any poverty of heart on his part. Nevertheless, for reasons that seem to have included the threat of a dangerous liaison, she had been forced, before that, into a ‘flight’ from her family: this is a word that is used of what Clarissa did, and Watson applies it to what Frances did. She later managed a happy marriage to Archibald, Lord Douglas, the claimant in the notorious legal imbroglio, to which Louisa Stuart awards only twelve words. Her words do not ventilate the suspicion that Douglas may have acceded to the ‘gay world’ of aristocratic England, with its impostors and hangers-on, as a French gypsy child smuggled in to secure a succession: as a changeling, no less.

Each of the texts is the work of a fine feeler, and Richardson’s was to set patterns of sentiment for later times. And yet he was also superbly plain-spoken, and shrewd. So was Louisa Stuart, who seldom yields at all culpably to the cant of fine feeling, and that only when the merits and miseries of her heroine are at issue. Of Townshend’s fondness for his stepchildren she observes: ‘the very desire of playing amiable (as it is called) might insensibly lead him to imbibe true affection.’ This is somewhat damaging to Townshend, but does not make him out to be empty: a poor heart does not so imbibe. Elsewhere, as both Louisa Stuart and Jane Austen cause us to be aware, playing amiable was an attribute of the tyrannical male.

Here and there, the two texts coincide. The memoir says that a daughter of Townshend’s by Lady Dalkeith was seen to step ‘into a post-chaise with a gentleman, and came home no more’. Here is another of the 18th century’s runnings-away. Miss Townshend came home no more, but was talked of, and deplored. The gentleman in the chaise was no gentleman but an Irish adventurer, or blackleg, evoked by Louisa Stuart with the air of some sprightly marchioness: he was like the apprentice, ‘a dirty ill-looking fellow not to be touched with a pair of tongs’, who was apt to arrive with tongs of his own, in place of Monsieur le Blanc himself, to dress a lady’s hair in time for a ball. ‘All his friends had ten thousand a year; he talked of his horses and his carriages, his estate and his interest; and when he addressed you as a lady, you could not help drawing back for fear he should give you a kiss.’ Miss Townshend, she writes, was ‘always vastly ill dressed’, her figure ‘what the vulgar call all of a heap’. In Clarissa’s letters that lady is ‘struck all of a heap’ on encountering a solemnity of countenance among her ‘dear relations’, as, in the knowledge of their cruelty to her, she chooses to describe them. Clarissa’s use of ‘all of a heap’ might seem to direct her, or her author, some way down towards the bottom of the heap, towards the vulgar. In terms of rank, Richardson the printer and writer stood below his hideous Harlowes, while they in turn are below Lovelace, who is also able to look down on the activities of politicians, on his uncle’s House of Lords. He is a great man, and the leader of a gang of gentlemen, but at times he is like some member of the unemployed, a doleman – the name, as it happens, of one of the gang. His own riotous activities give off all the more of an infernal glow in seeming to illuminate a desolation in which he and his friends have nothing to do. He is free to invent his life, his plots, as a writer might be; he is in certain respects marginal, as writers were often to be in times to come. The same doleful impression can be got from Restoration drama, to which – to its comedy as to its heroic tragedy – Richardson was attentive.

Louisa Stuart was, of course, above both the novelist and his imagined ladies and gentlemen. But it is of interest that, in 1802, she perceived in Richardson’s fiction ‘a thousand traits worth very great attention’, and that her maternal grandmother Lady Mary Wortley Montagu ‘despised’ this ‘strange fellow’, no doubt for reasons of class among others, but read him eagerly, sobbed over him, and thought the Harlowe family of the first two tomes of Clarissa ‘very resembling to my maiden days’. Richardson’s accounts of the ruling class and landed interest were not repudiated by Louisa Stuart, of whom it could be said that she was inward with both – indeed vastly well-connected, and widely respected in the highest circles. She was courted, as was Frances, by Pitt’s minister, the manager of Scotland, Henry Dundas.

A further verbal coincidence gives the note of Townshend’s wit, and a sense of the importance of tears for the society he lived in. On a visit to Edinburgh he is slighted, while much is made of his witch wife, who whines of a group of family retainers: ‘Observe the attachment of these poor people – Affectionate creatures! They are crying for joy to see me.’ Townshend rejoined: ‘Don’t be too sure of that, Lady Dalkeith. I believe, if the truth were known, it’s for sorrow to see me.’ Not the rejoinder of a man with a craven fear of his wife. A similar joke, which could well have been the parent of other such jokes, occurs in the novel, when Miss Howe exclaims: ‘Hickman will cry for joy on my return; or he shall for sorrow.’ The ambivalence of tears, which corresponds on this occasion to Miss Howe’s hot-and-cold treatment of her suitor Hickman, is a notion in keeping with the way in which Richardson tells his story of Clarissa’s quarrel with her kin.

This last coincidence is a stimulus to trying to say more about what the books have in common. They bear each other out in saying the same thing, and in taking it back, and in sharing an idiom – an idiom which may seem to be related, though usually indirectly, to this saying and unsaying, and which was subject like any other to the processes of historical change. Both writers show the life of the aristocracy and gentry as confining and cruel. Both question the ‘imaginary prerogative’, as Richardson calls it, of male supremacy. Both show women at risk, and men as the enemies of women, and as strangers to them. ‘Such are men,’ sighs Louisa Stuart, in reporting an insulting allusion to Frances by her brother. This may be a stock sigh of the sentimentalist, which can be compared with the ‘what wretches you men are!’ in Richardson’s Pamela; it is enough to remind one that Louisa was a common name for the distressed romantic heroine, as Jane Austen was to point out. But this sigh is not, in context, inane, or implausible.

Lovelace addresses his dear friend Jack Belford as ‘thou’, while Clarissa does not be-thou her dear Miss Howe. Hers is an eloquence which can often be read as a lesson to others, to an emergent public. In Clarissa Richardson, a male, was to produce a book whose real intimacies, as they may seem to a modern eye, and whose humour, are male, and whose male and female are at war: the uncertain evidence of its tutoyer might seem to suggest as much. And yet this is also a book which takes the side of its women. Elsewhere in Richardson the mode of address is used in order to show what an exercise of male supremacy is like. When Mr B be-thous Pamela, on an early occasion in the first novel, it is in order to reprimand her: ‘thou strange medley of inconsistence!’

‘God protect me from my friends – I can deal with my enemies myself.’ The saying is mentioned by Louisa Stuart, and attributed by her editor perhaps to Voltaire, perhaps to Maréchal Villars. It is a saying which is relevant to Clarissa, and which was to be deemed relevant – by Henry Dundas’s dangerously ambiguous dear relation Henry Cockburn – to the vagaries of late 18th-century kinship and political connection. In neither of these books, however, does the attitude it implies, the warning it harbours, escape qualification and retraction. Both are, in this matter of the family, medleys of inconsistence.

Richardson spoke out on behalf of the claims and merits of women, but he was careful to bear witness, too, to the case for order and deference within the family, and for the subordination of women. (He was to be gossiped about, incidentally, as a remote father to his girls and a punctilious master of servants.) On the status of women it is unlikely that Louisa Stuart would have disagreed with him. She has been credited with an acute, an insider’s grasp of contemporary politics, but she did not think that a female wisdom on the subject should be made public. Nor did she think that it became her either as a woman or as a woman of noble birth to publish her writings. She declined to be a bluestocking. And yet she speaks up for women in the memoir. The view of families and of females which is projected in both works is complex and wide-open to partial representation. It is a view which was bound to attract to itself ideas of contradiction and inconsistency. Contradiction and inconsistency were qualities of which the Augustan literary culture centrally disapproved, but which were often exhibited and enquired about there.

These works are the long and the short of a conception of family life which can be associated with the affective individualism claimed for the period. There are no pleas in Richardson for the sexual emancipation of women, and his opinions on education take account of an odious permissiveness among the better-off. It is nevertheless the case that this evangelical Christian, this enemy of the Enlightenment, devotes much of his energy in Clarissa to enabling us to understand profoundly how it could come about that a good young woman might move towards flying from her family. By the end of this interval of time permissiveness was on the way to abrogation. In the 1820s Louisa Stuart mentions a recent remark by a woman friend whose girls had ‘never heard of adultery in their lives’, which causes her to add that ‘so opposite was F.’s training that she heard of little else.’ While granting that Byron’s training had a good deal in common with Lovelace’s, and that Lovelace can be awarded a measure of parental responsibility for Byron, most readers now suppose that times had changed by the 1820s. It seems that there were then to be Victorians who objected to Richardson’s indecency. And yet the indecent Richardson was one of those who had been responsible for the change.

Family life was a subject which warranted the language of duality, and which was suitably accommodated by the dualistic epistolary novel, where authors refrain from exposition, and opposite points of view are sequentially heard. As the successive editions of Clarissa indicate, its author was keen to extract from his readers the right view, the improving view, of the behaviour of its principals; the novel grew, moreover, from the ethos of conduct books, and is itself a conduct book. But it could be said that even the decent and decorous Richardson was plunged into ambivalence by his use of letters.

One of the letters in Clarissa gives a blunt and unqualified account of filial duty. This happens when Mrs Howe apologises to the heroine’s mother for the unfortunate interferences of her daughter Anna Howe, Clarissa’s bosom friend. Mrs Howe is all for a ‘due authority in parents’, and Clarissa is portrayed as a ‘fallen angel’ who has suffered the consequences of her fault. ‘These young creatures,’ she writes, ‘have such romantic notions, some of love, some of friendship, that there is no governing them in either.’ Clarissa’s ill-treatment at the hands of Lovelace was ‘what everybody expected’, just as everybody now expects her to marry her rapist. Clarissa herself thinks that children should obey their parents, but that parents should not coerce their children unjustly. She comes to concede that she has indeed been at fault in placing herself in a situation where it was possible for Lovelace to cheat her into running away. But she then goes against what many of her acquaintances expect of her when she refuses to marry him. And a view of parenthood very different from that of Mrs Howe, who is seen by some of the scribblers as greedy and foolish, is apparent throughout. At no point in the history of its reception can many readers have travelled the novel without assenting to the reproofs it directs at an ungoverned patriarchy, towards totalitarian fatherhood – without taking the force of Clarissa’s words concerning her own father: ‘a good man too! – But oh! this prerogative of manhood.’ In other words, Mr Harlowe is an amiable patriarch who almost always behaves badly. Lovelace refers to Mr Harlowe’s way with a wife who did not dispute ‘the imaginary prerogative he was so unprecedentedly fond of asserting’. This is a prerogative which the heroine of the novel both regrets and accepts.

Anna Howe’s interferences are a challenge to it – but a challenge which Richardson sometimes seems to overrate. Her egotistical and arrested relation to her friend’s ordeal, when a few hours’ ride might have saved the day, is a source of discomfort for the reader, though a great help to the postal dimension of the novel: the remote control which she chooses to exercise very nearly begins to look like a filial deference to her mother’s wishes dissembled by cloying exclamations of love and friendship. The end of the novel appoints her to the undeserved role of honoured and shrilly censorious chief mourner.

The novel, then, says that patriarchy should neither be abused nor abolished, and in saying so sustains an element of uncertainty which has allowed it to be read and resorted to for a variety of reasons, which enabled it to be liked in the Romantic period and before for its exhibition of fine feelings, for its resistance to parents, while at the same time enabling it to appeal to believers in Christian duty and to believers like George Eliot in some secular equivalent. The novel as a whole is contradictory, and the picture it gives of the human mind is one that lays stress on contradiction. The story of Clarissa versus Lovelace is told in a fashion which has made it hard, for more than a few, to choose between the two, for all Richardson’s authorial and editorial efforts to obtain from his readership a severe condemnation of the latter. For all these efforts, he was obliged to regret that he met more people who sympathised with Lovelace than with Clarissa. While advancing – in what we might take to be a 19th-century way – the proposition that there were two sides to every question, Balzac was to ask: ‘Who can decide between a Clarissa and a Lovelace?’ Not only is the novel he inhabits contradictory, moreover: Lovelace himself is. He is seen as inconsistent by the people of the novel, which was written at a time when it could readily be agreed that inconsistency was a bad thing. That agreement was not destined to survive. And Richardson’s picture of the mind can be examined in the hope of showing that it makes sense to think of his fiction as a bridge between Renaissance and Romantic duality.

In discussing the literary use of the double or doppelgänger, and of divided identity, from the Romantic period to the present, I have written in the past about a number of recurrent dualistic formulations: about the idea of ‘inconsistency’, of the strange case, of the ‘strange compound’ in the domain of personality or temperament (another word for ‘compound’ in former times), and about the figurative use of the verbs to ‘soar’ and to ‘steal’. Such a use of the second word can be culled from Richardson’s novel, where Clarissa cries, ‘Oh that I were again in my father’s house, stealing down with a letter to you’ (and where she is later to deceive Lovelace by means of a heavenly double-entendre for the phrase ‘my father’s house’). In the fiction of Romanticism the image of the double is put with that of the orphan, and is shadowed by the stock figure of Proteus, a name for the changeable self. Or so I tried to argue. And I tried to suggest that Romanticism offers versions and transformations of the confessional sentiment: ‘I can’t decide whether or not to break with my friends, whether or not to leave my father’s house.’ It is a sentiment which can appear to be linked to a rift within the self or to a repertoire of selves. But it is not a sentiment which the Romantics were the first to express.

In relation to Romanticism there is a prehistory of such terms, and they are important items among Clarissa’s million words. Clarissa herself is called an orphan and a ‘romantic creature’, and Lovelace, that creature of disguises, is called a Proteus, a thief, a ‘strange wretch’. His mind is a ‘strange mixture’. The word ‘strange’ is often used in the novel, where it bears the standard sense of someone or something from beyond the decorum of familiar and of family life – a sense which also appears in Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s reference to Richardson, that creature from another class, as a ‘strange fellow’.

Wretches are strange, strangers are wretches. And yet we are all strange in being wretchedly mixed-up. A standard, indeed perennial conception is expressed by Lovelace’s friend Jack Belford: ‘What wretched creatures are there in the world! What strangely mixed creatures! – So sensible and so foolish at the same time! What a various, what a foolish creature is man!’ Similar statements are made in turn by Lovelace and Clarissa. The former writes: ‘Everybody and everything had a black and a white side, as ill-wishers and well-wishers were pleased to report.’ And Clarissa writes: ‘with what intermixtures does everything come to me that has the appearance of good’ – such as that good man, her father, one might reflect. Amiable is odious. And Lovelace himself is both amiable and odious – both simultaneously and successively so. Like Charles Townshend, he is volatile. Clarissa tells him: ‘there is a strange mixture in your mind.’ Lovelace responds to that opinion of hers, and mentions his ‘inconsistency’. At this point in the novel Richardson inserts a footnote which observes that his character’s actions have been consistent with a principle of inconsistency. Lovelace is black and white, loving and vengeful towards Clarissa, masterful and conspiratorial but also generous and witty, and alert to the life about him. Balzac’s question is far from incomprehensible.

The Richardson scholar A.D. McKillop has said of the writer: ‘He was aware that the “heroic total of great opposites” in this character made the ethical teaching of the story less unequivocal than his admirers expected.’ Richardson’s faith disposed him against equivocation, against duplication: his was a faith which held to ‘the one thing needful’. And yet he seems to have felt that opposites could be great and an accumulation heroic. He did not give himself, or his admirers, what was expected. His novel is a mixed creature. Meanwhile Lovelace’s, and the novel’s, inconsistency is certain to have appealed to a Romantic prejudice which was then in the process of formation – to the outlook of the author of Don Juan, for instance, with its dogmatic inconsistency. This is a poem in which ‘consistent’ is rhymed and contrasted with ‘existent’, and writers are advised that they can’t afford to be inflexible if they are to describe the way things are, the mixture of things.

The strange mixture of Lovelace’s mind can be compared with the ‘brittle compounds’ that Belford says that all minds consist of, male and female, and with Lovelace’s remark to Belford: ‘Different ways of working has passion in different bosoms, as humour and complexion induce.’ Mixture, complexion, compound, humour – Richardson’s picture of the mind has residues, and more, of the Elizabethan world picture. If Lovelace is a creature of shifts and disguises, he is also a sublunary creature who speaks of rising and flying, and of the black and white of an up and a down. He is not an atheist or a scientist, as Richardson took care to devise, and the old knowledge of a flight in the direction of the spheres of angelic intelligence, and of a drop to damnation, is repeated in him. Equally, it is Elizabethan of Miss Howe to mention a ‘general scale of beings’, with its high orders and low. Romanticism was sometimes to reiterate a pre-scientific cosmology and psychology, drawing on Shakespeare above all, and Richardson could well have been influential at an intermediate stage in the process of transmission and recall. He looks forward to the Romantics: in his dislike for the Enlightenment he also looks back, as the Romantics themselves were often to do.

Richardsonian inconsistency had recourse, therefore, to an old idea of the mind, to the doctrine of the elements or humours which had once enjoyed its most exotic application in the dualistic compoundings of alchemy. It did this at a time when such notions were widely dismissed as magic, and when inconsistency was especially unpopular, when there was a righteous common knowledge of it, and a use of adages on the subject with which to scold an inferior, and when Samuel Johnson could assert that ‘a poet may be allowed to be obscure, but inconsistency can never be right.’

The Elizabethan words ‘humour’ and ‘temperament’ signified a balance or imbalance between the four elements (earth, water, air and fire) or the four humours (melancholy, phlegm, blood and choler) present within the human being and throughout the created world. Gold was produced, and the golden or perfect man was produced, when the elements were rightly proportioned. But since the Fall human beings have been imperfect – strange mixtures. An equal mind – a name for composure which is dropped in Clarissa – required this same balance of constituents. In Richardson’s day, as of old, human life could be seen as inherently unequal, unstable, brittle – the old idea of balance having been crowned with the promise of endurance, and indeed immortality.

These matters are treated in the poetry of Donne, which declares that all souls contain ‘mixture of things, they know not what’. The souls of two lovers may become one, in a manner which is recalled when Miss Howe swears that Clarissa is the better ‘half of the one soul that, it used to be said, animated the pair of friends, as we were called’. The souls of his lovers have been equally or harmoniously re-mixed, according to Donne, who also believed, or declared, that ‘Whatever dies, was not mixed equally’: so that this symbiosis of lovers might seem to be going to last for ever. Here, then, was an outlook of the past which still meant something to Richardson: and perhaps it is not as implausible as it can seem in some of Donne’s teases. We might well believe we are mixtures, and not know what the mixture is, or of what it is. It was an outlook which had not disappeared by the time of the Romantics, who were, in fact, to deepen and develop it, and to subject it to further teases. By this time the outlook had come to be ruled by the idea of the strange compound. This denoted an identity dangerously divided, and there was to be a zealous and at least half-approving interest in such persons, real or imaginary, who could be called by this name: James Hogg was described by a fellow dualistic writer as a ‘strange compound of genius and imbecility’. In the course of the 18th century the strange mixture was on the way to becoming the divided self of the romantics, and to suggesting some conflict of motives or drives, or the advent to consciousness of some previously unacknowledged portion of the self. This outcome received an early recognition from Diderot, Richardson’s enthusiastic admirer, who believed in balance and believed that a man may be ‘torn between two opposing forces’.

Neither in the middle nor at the end of the British 18th century was the relationship between complication of mind and a complex view of the family depicted as straightforward or self-evident; in the novel Clarissa it is very subtly registered, and can never be said to be expounded. But it seems clear, in general, that complication of mind will often be revealed in relation to those codes and submissions which have found their main proving-ground in the context of family life. The complicated Lovelace, after all, is part author of Clarissa’s breach with her family, and the counter-impulses to his disruptiveness are such as to pose the question of her restoration to the realm of the family. But she refuses to be restored. In the matter of marrying your attacker, Clarissa gloriously refuses to do what Pamela gloriously does. At a time when inconsistency could never be right, Richardson’s portrayal of family life could be richly inconsistent.

At this point it is worth consulting Louisa Stuart’s memoir once again. Just before Frances’s marriage, a scene is played out beneath the elms of Hyde Park, during which she reveals herself to Louisa Stuart as having been every bit as much of a strange mixture as Lovelace, every bit as volatile as Townshend. She, too, has been possessed by an unequal mind. But now at last, she says, she is in a fit state to marry her ‘safe man’. The scene itself belongs to the 1780s: but the account of it could well belong to the romantic 1820s.

The inequality of her spirits which could not be disguised, the deep dejection which would succeed her greatest gayety, the efforts she often seemed making to employ and interest herself about odd trifles not worth her attention, the expressions she would drop (as if half in joke) fraught with some meaning more melancholy than met the ear – all this ought to have told me the tale beforehand – To give an instance; one morning when, sitting with us, she had been most transcendantly agreeable, flashing out brilliant wit, stringing together a thousand whimsical images, my mother quite charmed with her exclaimed – ‘What a happiness it is to have such an imagination as yours! You must enjoy a perpetual feast’ – ‘Ah!’ returned she – ‘So you may fancy, but I am afraid I know better. I often feel convinced I have two Selves: one of them rattles and laughs, and makes a noise, and would fain forget it is not alone – the other sits still, and says – Aye, aye! Chatter away, talk nonsense, do your utmost – but here am I all the while; don’t hope you are ever to escape from ME’ –

The tale is that for several years Frances had been the prey of a ‘fixed, deep-rooted, torturing passion’ for a certain unworthy man. This female affliction, as it is made to seem, placed her in a quandary which brought about her inequality of spirits, these alternations of mood, the dejections which followed her flashes of wit – flashes in which, however, the memoir does not enable us to believe. The experience may account for the two selves to which she laid claim, and for which it seems that she was to be both pitied and admired. And it may account for her saying, when she came to study the little stretching paws of her infant daughter Caroline, who was to be the recipient of the memoir: ‘is not that exactly what we are all about throughout our whole lives; continually stretching and reaching at something, we hardly know what, and some other thing stronger than ourselves always pulling us back?’ Back to ‘common life’, she means, back to those ‘domestic feelings’ which Louisa Stuart contrasts with the emotion of love. Frances says with Donne that we don’t know what we are, what we are made of, and there were women who did not know what love was. It was rumoured of the Duchess of Buccleuch that ‘she did not understand that sort of thing.’ (Louisa’s italics.)

Her refusal to accept this Lovelace of hers, who makes one think of a second Townshend, has placed Frances on a footing with Clarissa. The scene continues:

‘I will not tell you, said F., that he ever felt what I did, nor perhaps is he capable of it; yet at one time I could not doubt that he was extremely inclined to make me his proposals, and would have done so on a very little encouragement. But no – Oh no, no! – I had just – only just enough of reason left to see that this must not be – that we must never marry – it would have been worse than madness to think of it – And I withstood the temptation like a famished wretch refraining from the food he knows to be mingled with poison.’

Having reported this strong image for the divided self, Louisa Stuart goes on to say that the wretch ‘had suffered the torment of striving and striving without success to detach her affections from one whom her understanding and principles forbade her to approve, and would even have compelled her to reject’, and to explain that a crisis was reached when the man

frankly avowed himself an unbeliever, almost to the extent of atheism. ‘I could hardly bear up ’till I got home, said she; then I gave way at once and cried all night with a sensation of despair not to be described’ –

Frances, who was to fly from that home, was also, it turns out, to refuse to leave it for a man whom her principles could not approve. Lovelace, we remember, was not permitted to stray into atheism. Nor is he credited with the possession of two selves, a state which would not have suited that old world of coaches and six, of powder and pomatum. It is the momentous possession of opposing selves which was to mark the fiction of romantic duality.

Richardson’s text and Louisa Stuart’s are stations on a progress towards the subject-matter and appeal of romantic fiction – towards, let us say, James Hogg’s Confessions of a Justified Sinner, which was written at about the same time as the memoir, and in which duality and family are mixed in a mysterious way – but in a way that can be investigated. With their dubious families, their principles, their patent good sense, their sentimental ardours, the two women of the memoir may be thought to stand in an ambivalent relation to the romanticism which arrived in the course of their later lives: such ambivalence is likely to accompany an interval of transition, and intervals of transition are likely to be propitious to the formation or intensification of a cult of ambivalence. All times are times of change, of course: but at a time when an important change is recognised to have occurred, it seems appropriate to look for the operations of the changeable mind, which is both for and against family life, and which both encounters and refuses the future. The memoir carries disparagements of the romantic, as we have seen; Frances did not run away with her unworthy man, what’s more, and Louisa Stuart’s sympathy with her friend’s sternness in this respect is taken for granted. It went without saying. Nevertheless, the narrator plainly sympathises with the torment and division experienced by her friend, and this is a sympathy which accords with literary innovations of the earlier 19th century – with the novels of Scott, for instance, themselves compounded of reason and romance.

For Richardson, too, the word ‘romantic’ had a pejorative meaning: and yet his novel’s disparagements of the romantic are assigned to ill-wishers. It is Clarissa’s bad brother who speaks of her as a ‘romantic young creature’, filled with a perverse female ‘tragedy-pride’, who was of an age to be ‘fond of a lover-like distress’. The novel powerfully displays the operations and indomitable purposes of a heroine who frequently appears to be quite the opposite of any romantic creature, and whose purposes have appeared strange and morbid to the readerships of later times. But it also served those of the generations that followed who would rather have read of a young woman running from her family than of a young woman who loses her chastity and wills her own death. There were then to be those who believed, or believed with a new intensity, in an individual psychology of opposing forces, contending sympathies, who believed in an interesting inconsistency, and in the kind of artist who takes equal pleasure in creating an Iago and an Imogen, a Lovelace and a Clarissa. Such readers, too, had reason to admire Richardson’s novel.

He called it a ‘history’. It is also a romance, and an example. He called it a work ‘of the tragic kind’, and it is that too. The work exacerbates the Christian confidence in a hereafter; it does not fit with the tragedies which are called by that name in academies of learning, and preferred to all other works, and which very often lack a hereafter. But the contradictions of Clarissa can be compared with those of the canonical tragedies, and the novel should not be shut away from them, and put with what specimens we are able to remember of the Restoration stage tragedies to which he attended. It is an aspect of Richardson’s tragic work that it was to prove as capable of inviting as of precluding romantic sympathies, and that the history of its reception affords as much as it does in the way of contradiction and change. There are relatively single-minded works which have had a similar history. But it may be that, in the case of Clarissa’s relation to such a history, the element of cause and effect is more than usually decipherable.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.