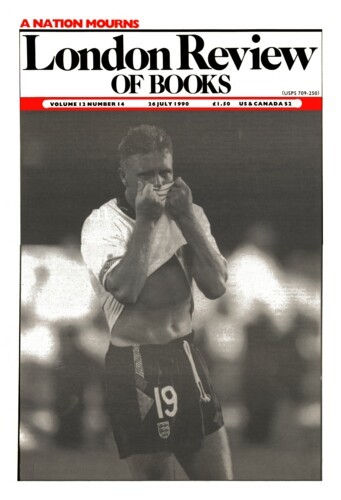

‘Of all nations’, writes Ian Ousby, ‘we’, the English, have ‘perhaps the most strongly defined sense of national identity – so developed and so stylised, in fact, that we are frequently conscious of it as a burden or restraint’. I wonder what he can possibly mean by that. The most anomalous thing about England in comparison with all other European nations (of course it isn’t a nation, but even in comparison with Scotland and Wales) is that it doesn’t have the formal marks of national identity acquired even by Iceland or Finland, Luxembourg or Albania. It has no national anthem – ‘God save the Queen’ is played at football matches, but that is shared with other parts of the UK, who, however, don’t play it (except for the Northern Irish, who are making a political point). It has no national dress, nor any evident national icons in the tartan/leeks/thistles class. St George’s Day attracts no celebrations. It does have a national flag, but not everyone knows what it is. A football commentator remarked that he was pleased to see ‘nearly as many’ St George’s Crosses being waved as Union Jacks, when England played Cameroon in the World Cup. No Union Jacks were on display at Scotland’s games. At a recent conference in Denmark I asked some forty Danish Anglicists if they knew what the English flag looked like. Yes, they replied, it’s that red, white and blue one with crosses going different ways. At least they were pleased to discover that the English flag is the exact reverse of the Danish one, for, as Saxo Grammaticus wrote long since, history in the North began with two brothers, whose names were Dan and Angul. But that particular national myth is unknown in England.’

England and Englishness: Ideas of Nationhood in English Poetry, 1688-1900 by John Lucas. The Englishman’s England: Taste, Travel and the Rise of Tourism by Ian Ousby. Fleeting Things: English Poets and Poems, 1616-1660 by Gerald Hammond. ‘Of all nations’, writes Ian Ousby, ‘we’, the English, have ‘perhaps the most strongly defined sense of national identity – so developed and so stylised, in...