Ruth Bernard Yeazell

Ruth Bernard Yeazell is Sterling Professor of English at Yale. Her most recent book is Picture Titles: How and Why Western Paintings Acquired Their Names (2016).

A Favourite of the Laws

Ruth Bernard Yeazell, 13 June 1991

In Of the Rights of Persons, the first volume of his celebrated Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-69), William Black stone concluded his account of how the law makes a husband and wife one person by suggesting that the legal disappearance of the married Englishwoman was effectively a tribute to her sex. ‘These are the chief legal effects of marriage during the coverture’, Blackstone wrote, ‘upon which we may observe, that even the disabilities, which the wife lies under, are for the most part intended for her protection and benefit. So great a favourite is the female sex of the laws of England.’ Perhaps not surprisingly, Blackstone’s sisters now tell a different story. For Susan Staves, whose book takes its impetus both from feminism and from critical legal studies, to analyse the history of married women’s property in England is to uncover the ‘deeper’ structures of patriarchy – the system by which men manage to perpetuate their power by transmitting wealth from one generation to the next. The aim of the law, as Staves interprets it, is to ensure that women have as little independent control as possible of the wealth that passes through them.’

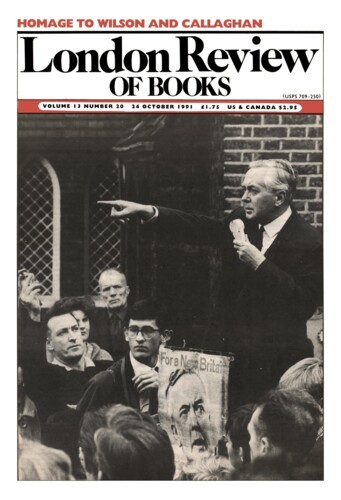

Tears before the storm

Ruth Bernard Yeazell, 24 October 1991

It was front-page news in the United States recently when George Bush brushed away a tear as he described how he had wept while deciding to unleash the air war in the Gulf last January. ‘Like a lot of people, I’ve worried a little bit about shedding tears in public or the emotion of it,’ he told a convention of Southern Baptists in June, but ‘as Barbara and I prayed at Camp David before the air war began, we were thinking about those young men and women overseas. And I had the tears start down the checks, and our minister smiled hack, and I no longer worried how it looked to others.’ As his voice broke, and he paused to dab at his check – ‘Here we go,’ he said, with an embarrassed grin – the audience burst into applause. Like the smiles of the minister in January, the cheers of the Baptists in June presumably commended both the President’s war and his weeping.’

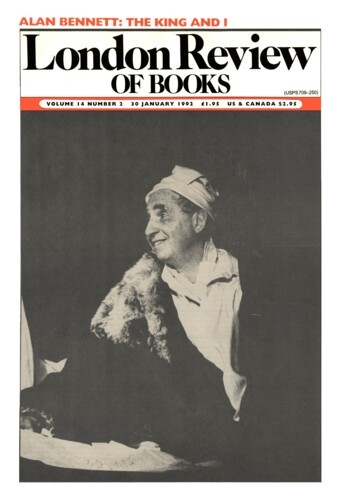

Mongkut and I

Ruth Bernard Yeazell, 30 January 1992

In Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical, The King and I, the English governess quarrels with her royal employer over his refusal to provide her with a separate house, outside the harem walls. Alone in her room afterwards, Anna takes her revenge with a spirited patter song, indignantly denouncing the King as a ‘conceited, self-indulgent libertine’ and seizing the occasion to inform him in – absentia – of ‘certain goings on around this place/That I wish to tell you I do not admire.’’

Drawing-rooms are always tidy

Ruth Bernard Yeazell, 20 August 1992

Among the hot items at my local video store these days is a recent Hollywood thriller called The hand that rocks the cradle. A successful instance of what might be called the yuppie nightmare film, this particular contribution to the genre also manages to exploit a tear that must trouble every mother who has temporarily handed over the care of her children to another woman – not the dread that the caretaker will harm or neglect them, but the anxiety lest she win their love away. An early scene of the film adroitly converts one kind of anxiety to the other, as the audience watches the new nanny, pillow in hand, threateningly approach the baby’s cradle as if to smother him, only to discover that she is intent instead on a secret session of breastfeeding. At the climax of the film, mother and nanny battle to the death in the attic (‘It’s my family!’ the heroine exclaims), while the man of the house lies immobilised with a broken leg three storeys below. The hand that rocks the cradle capitalises on several sources of female anxiety: the entire chain of events begins when the heroine reports her obstetrician for having sexually abused her during an examination, while before the elaborate plot has run its course, it also feints with the threat of the other woman in the more familiar sense, in the guise both of the husband’s former girlfriend and in that of the nanny herself, who repeatedly attempts to seduce him. But the real horror of the film clearly emanates from the nanny’s insidious campaign to supplant the biological mother in the affections of her children.’

Pieces about Ruth Bernard Yeazell in the LRB

Slipper Protocol: the seclusion of women

Peter Campbell, 10 May 2001

Imagination must take the strain when facts are few. As information about the domestic life of polygamous Oriental households was fragmentary, 17th, 18th and 19th-century European writers and...

Preceding Backwardness

Margaret Anne Doody, 9 January 1992

Both of these books are on ‘women’s subjects’. That is to say, they deal with the major arrangements of a society in its (usually uneasy) dispositions of property and power,...

Death and the Maiden

Mary-Kay Wilmers, 6 August 1981

Alice James died, not trembling, but, said Katharine Loring, ‘very happy’ in the knowledge that the Last Trump was at hand.

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.