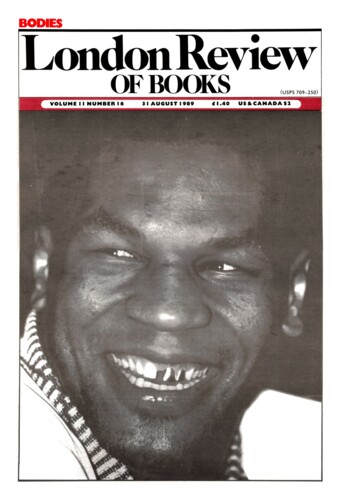

Body History

Roy Porter, 31 August 1989

Suddenly, everyone seems to be writing about the body, and eyebrows are being raised. ‘What sort of history is the history of the body?’ asks Peter Biller in a recent review, voicing scepticism about the genre itself: even ‘a moderate example of body history’, he concludes, ‘can principally incarnate a certain blindness towards the past.’ Do academics feel similarly hesitant about studying more cerebral things – ideas, for example? Cold-water treatment of this kind merely proves the point historians of the body are making. We have lived too long within our Platonic, Pauline and Cartesian prejudices; we value the mind (no complaint about that), but deny the flesh, so that we no longer even entertain its history.’