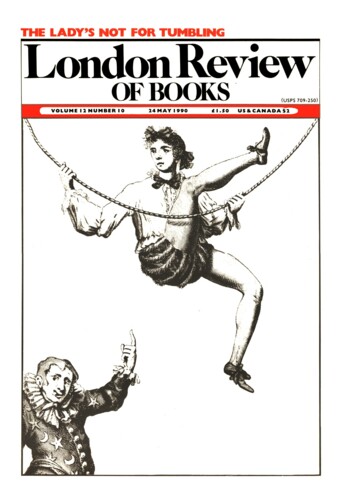

Mrs Thatcher’s Ecstasy

Ross McKibbin, 24 May 1990

The local government elections have come and gone (more or less) as expected. Labour did not do as spectacularly well as some predicted, and in the event the caution of the Labour leadership was justified. The Conservatives did better than they feared they might. But they would be unwise to find too much consolation: Labour gains were not as spectacular partly because Labour was defending such a large proportion of the seats anyway, and partly because the increase in the Labour vote was not matched by a proportionate gain in seats. It is possible that the Government’s strategy of blaming high poll taxes on Labour councils had some effect in areas (like London) where memories of ‘loony’ left-wing councils are strong, while in Westminster and Wandsworth the electorate clearly behaved in a cheerfully Thatcherite manner. On the other hand, the Tories did badly in a number of areas where their own councils set low poll taxes. There is, in fact, not much evidence that the electorate has changed its mind about the poll tax and the result of the Mid-Staffordshire by-election would still seem to represent accurately the public view. The best the Government can hope for is that the electorate will become habituated to it; and we can be certain that nothing – including money – will be spared to ensure that it does.’