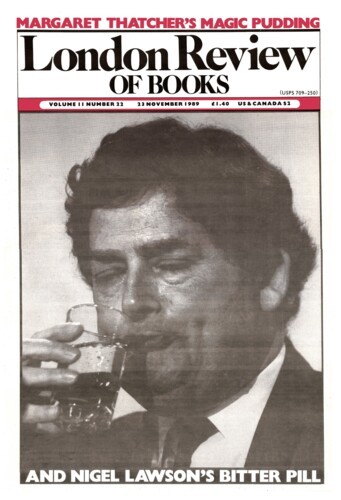

Diary: Mrs Thatcher’s Magic Pudding

Ross McKibbin, 23 November 1989

Although Mrs Thatcher and Mr Lawson are closely associated in the public mind, their aspirations are very different. Mrs Thatcher, for her part, is not really interested in the economy at all. She has little idea how it works, no notion of its complicated and delicate relationships, and only the most elementary conception of how it might work better. Sceptical would-be supporters of the Government used plaintively to enquire why the Prime Minister allowed herself to be ‘sidetracked’ by marginal matters – why someone so anxious to promote the free market should be so obsessed with secrecy, censorship or the Poll Tax. That is not the right question. The question is: why should someone so obsessed with secrecy and censorship have any interest in the free market? In fact, insofar as her Thatcherism has a clear focus, it is the establishment of a reactionary moral and political order in which the free market performs a disciplinary and not an allocationary function. The free market, as political economists know, is a harsh disciplinarian, the more effective because its tenets are expressed in apparently impartial terms. But free-market ideologies are purely instrumental to Thatcherism: she uses them when they promote her political order and she abandons them when they obstruct it. Indeed, in several important ways Thatcherism is antithetical to the free market. Her principal preoccupations are the restoration of authority and hierarchy, and it is this she means when she speaks of the ‘defeat of socialism’. Her ambition has always been so to entrench the Conservative Party that people will vote for it as of second nature – and not just any old Conservative Party but a particular version of it. The overriding object of her government, to which the free market has always been subordinate, has been political mobilisation, and she has pursued it with determination. It is precisely because their goals are so different that deregulating Antipodean Labour prime ministers get cross when their policies are described as Thatcherite.’