Thatcher’s Artists

Peter Wollen, 30 October 1997

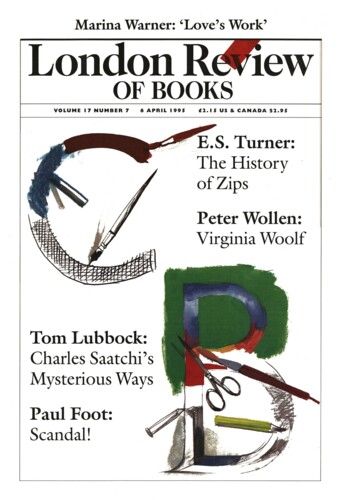

Art catalogues have drifted away from being simple accessories to exhibitions and become instead strange hybrid forms somewhere between cultural studies primers and coffee-table books. They provide both an intellectual commentary, written by academics, journalists and art-world figures, and a comprehensive set of colour reproductions of the works in a show, taken by specialised photographers. From a practical point of view they are freebies for the press, commodities to be sold in the museum store and in the wider world, promotion tools for the museum and the artists and, perhaps most important of all, they endow exhibitions with a durable after-life in libraries, both private and public. The catalogue for Sensation, the show of works by young British artists from the Saatchi collection, currently on view at the Royal Academy of Arts in Piccadilly, runs over two hundred pages, with more than a hundred colour plates, as well as a series of black and white portrait photographs of the artists taken by Johnnie Shand Kydd. It has five catalogue essays, several pages of artists’ biographies, a bibliography and, as the very last item in the book, a six-page checklist of the 110 works in the exhibition, with an apparatus of dates and dimensions. The cover design of the book is not drawn from the works on display in the show but was produced for the book by a design company. It is as vivid and arresting as the artworks documented inside, perhaps even more so.