A Journey through Ruins

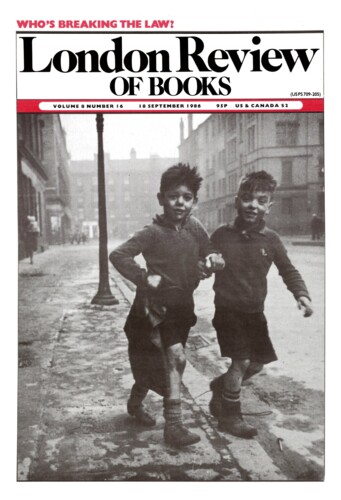

Patrick Wright, 18 September 1986

Douglas Oliver’s books have been appearing since 1969. Slim volumes published in tiny editions by marginal presses, they have escaped all but the slightest measure of attention. This may be the usual story for poets, but Oliver – a former journalist who is now teaching in Paris – is developing an unusual poetic which deserves wider interest. His most abiding themes have an autobiographical dimension. Repeatedly, for example, he returns to a mongol son who died in infancy, just as – across another tormented distance – his writing also comes back to the fragmentary and unverifiable stories of Tupamaros guerrilla activity in Uruguay which Oliver used to receive when working on the night desk at a Paris press agency. Grounded in personal experience, the writing nevertheless has the literary capacity to transform everything it finds there. In some striking passages of The Diagram Poems (1979) the ‘stupidity’ of the lost infant can therefore become affirmative in a critical and always unresolved way: casting a searching and unpredictable light on the indistinct politics of revolutionary violence and its barbaric suppression.’