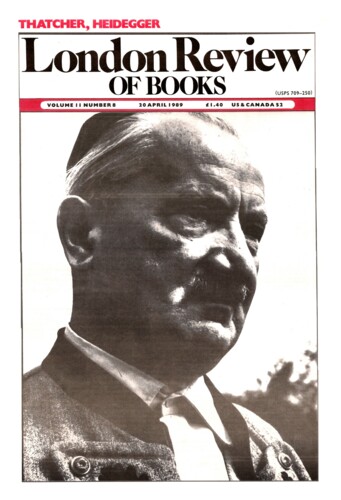

Jolly Jack and the Preacher

Patrick Parrinder, 20 April 1989

‘I belong to the Beardsley period’, said Max Beerbohm, thereby beginning one of criticism’s most imperious habits. The authors of scholarly books such as The Shakespearean Moment, The Pound Era or The Auden Generation are following Beerbohm’s precedent in appropriating a cultural epoch under the name of a single artist. Yet, as D.L. LeMahieu points out, the great majority of their contemporaries had never heard of, still less read, these totemistic figures. A Culture for Democracy is concerned to argue that there was a genuinely common culture in mid-20th-century Britain, a culture which embraced ‘the unemployed labourer in Huddersfield, the Oxford don, the shopkeeper in Leeds, and the typist in Grimsby’. The book pursues cultural history by the accumulative method, piling up instance on instance and secondary source on secondary source; those in need of the information it contains will find that it amply repays study. LeMahieu conscientiously shuns autocratic value-judgments and their advocates, but his approach is more literary and imperious than at first appears. He, too, has his culture-heroes and representative spokesmen.