Auchnasaugh

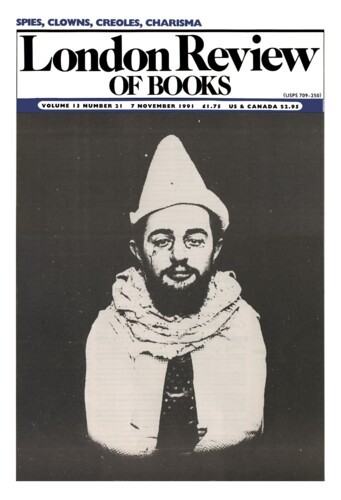

Patrick Parrinder, 7 November 1991

David Craig has an unfashionable concern with truth-telling in fiction. In his earlier role as a literary critic, he wrote a book called The Real Foundations in which he showed how some of the most respected 19th and 20th-century novelists and poets had blatantly falsified social reality. If a work of realistic fiction is to be convincing in general, according to Craig, it ought to convince us in particulars. Now he has written a historical novel which opens with the solemn affirmation that ‘many of the people, incidents and other items in this story are real. Where a fact existed, I have never knowingly substituted an invented item for it.’