Patrick Parrinder

Patrick Parrinder is a reader in English at the University of Reading. His books include Authors and Authority and Science Fiction: Its Criticism and Teaching. A study of James Joyce has recently appeared.

Cover Stories

Patrick Parrinder, 4 April 1985

‘Here’s something out of the quaint past, a man reading a book,’ remarks E.L. Doctorow’s narrator as he rides the New York subway. The other passengers in the subway are not readers but listeners, hooked to their earphones and tape-players, ‘listening their way back from literacy’. And before literacy? ‘The world worked in a different system of perception, voices were disembodied, tales were told.’ If tale-telling is the sign of a primitive culture, we – this would seem to imply – have the novel; and the more self-consciously civilised among novelists have sometimes been anxious to disclaim the form’s own origins. As E.M. Forster wearily put it, ‘Yes – oh dear yes – the novel tells a story.’ But storytelling will outlive the novel, and it is also elemental to the novel. It is not coincidental that each of the books under review ends with the lure of a further, untold story: a story which might or might not turn out to be the one we have just read.’

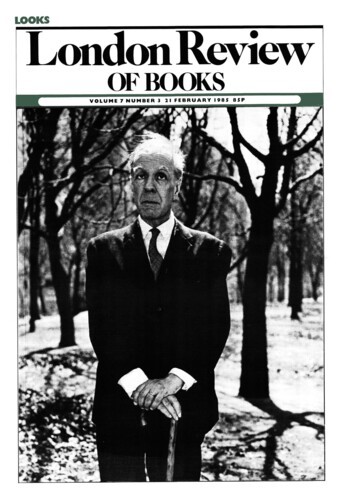

Father, Son and Sewing-Machine

Patrick Parrinder, 21 February 1985

Once upon a time the novelist’s task was to be realistic and to tell a story that was lifelike, convincing and ‘sincere’. Today’s novelists are counter-Aristotelians, spinners of tall tales and colourful yarns, engaged, as it seems, in some eternal childlike competition to impress their hearers and see who can get away with telling the biggest whopper. Each of the three novels under review reads, at times, like a gigantic leg-pull. Yet all three are historical novels, set in the first half of the present century and significantly concerned with world war, its origins and aftermath. Garden, Ashes and Star Turn, though unlike in most other respects, share a preoccupation with the Holocaust.

Pamphleteer’s Progress

Patrick Parrinder, 7 February 1985

Terry Eagleton’s books have been getting shorter recently. It is eight years since he offered to re-situate literary criticism on the ‘alternative terrain of scientific knowledge’; three since, self-canonised, he included his name in a list of major Marxist theoreticians of the 20th century. The Function of Criticism is a history of three centuries of English criticism in little more than a hundred pages. Its conceptual basis seems (not for the first time) to have been hastily borrowed for the occasion. The scholarship is cobbled together from the works of others. Since he makes great play with the split between the professional and amateur pretensions of literary critics, it would be tempting to adapt his own style and portray him as the helpless victim of contradictory impulses. Yet in many ways he thrives on contradiction. His struggle against ‘bourgeois’ criticism has the agility, the opportunism and the sniping provocativeness of a guerrilla campaign. Though his books have grand titles, he has lately abandoned any pretence of working towards a Grand Theory. His recent work has consisted of critical introductions, essays, and theoretical pamphlets like the present one.

Literary Criticism we could do without

21 February 1980

Pieces about Patrick Parrinder in the LRB

Devil take the hindmost

John Sutherland, 14 December 1995

Among other certain things (death, taxes etc) is the rule that no work of science fiction will ever win the Booker Prize – not even the joke 1890s version. H.G. Wells’s The Time...

Outside the Academy

Robert Alter, 13 February 1992

These two meticulous surveys of modern criticism in all its vertiginous variety lead one to ponder what it is all about and where it may be heading. The book by René Wellek, focused on...

Post-Humanism

Alex Zwerdling, 15 October 1987

When the history of late 20th-century literary culture comes to be written, the extraordinary vogue of metatheoretical works will surely require explanation. What can account for the obsessive...

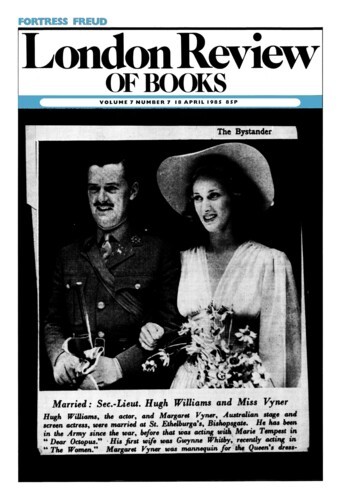

Raiding Joyce

Denis Donoghue, 18 April 1985

Patience is a mark of the classic, according to Frank Kermode. ‘King Lear, underlying a thousand dispositions, subsists in change, prevails, by being patient of interpretation.’ It...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.