Patricia Craig

Patricia Craig whose books include The Lady Investigates: Women Detectives and Spies in Fiction, written with Mary Cadogan, is working on a study of Northern Irish poetry and fiction.

Belfast Book

Patricia Craig, 5 June 1986

The first of these writers, M.S. Power, has a searing metaphor to describe the effect of Ireland on certain people, those native to it and others: nailed to the place, they end up as in a crucifixion. ‘You and I are a crucified breed,’ says one leading terrorist (half-way through his latest novel) to another. ‘Just set foot on the soil of Ireland and you’ll be crucified to it forever,’ thinks another Power character, an honourable English colonel (retired), recalling the words of a high-up republican, or – it may be – an RUC inspector. Ireland – or, to be specific, Northern Ireland – has these people in its deadly grip. Lonely the man without heroes is the second volume of Power’s projected trilogy entitled ‘Children of the North’. Out of the north – to reverse an old Gaelic saying – comes the utmost despair. The Power novels are set in Belfast, but a Belfast deprived of every feature that gives it its character. As in the ordinary thriller, it’s become the scene of opposing stratagems, nothing more. Such books contain no sense of life going on in the usual way, in the teeth of military and paramilitary activity. Some authors – Power and Maurice Leitch, for example – clearly have a symbolic design in excluding the social and domestic from their work. They mean to stress the balefulness of what’s been brought about, by isolating the deformation of life in the city. (Authors in pursuit of a cruder kind of drama tend to lumber their characters with sets of convictions, among other things, resembling the bag of swag borne about by a comic-strip burglar.) With this approach, though, what’s lost – along with certain refinements of characterisation – is the atmosphere in which violent measures are condoned and enacted.’

Green Martyrs

Patricia Craig, 24 July 1986

Each of these books – two anthologies and a critical study – is notable for its exclusions, among other things; each takes a strong line over questions of definition and evaluation; and each contains much to applaud. Thomas Kinsella’s New Oxford Book goes right back to the beginning, to a rath in front of an oak wood singled out for comment by some anonymous poet of the sixth century, and cherished as a survival from an even more distant past, while the Faber book takes as its starting-point (as the blurb has it) the death of Yeats. The American publisher and critic Dillon Johnston plumps for Joyce, rather than Yeats, in his title: not on a whim, he tells us, but in acknowledgement of certain literary procedures sanctioned by Joyce, and afterwards available to poets, no less than prose-writers. The lofty tone perfected by Yeats didn’t do at all when it came to the bleakness and piecemeal quality of the post-Yeats world, so many poets found. Joyce’s more variable manner showed a way to take in every aspect of the new social conditions, and keep the end-result tricksy.’

Open that window, Miss Menzies

Patricia Craig, 7 August 1986

The epigraphs of P.D. James (now that she has taken to using them) are important. ‘There’s this to say for blood and breath,’ runs the latest one, from A.E. Housman: ‘They give a man a taste for death.’ Are we being directed to hold in mind those other lines of Housman’s?

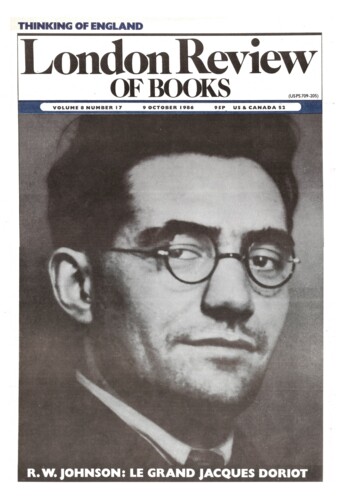

The Shirt of Nessan

Patricia Craig, 9 October 1986

Piers Paul Read’s Free Frenchman is Bertrand de Roujay, whose most significant act is to repudiate Pétain and his expedient administration at Vichy, and take himself to London, clandestinely, where he throws in his lot with the more honourable and recalcitrant de Gaulle. The year in which these events take place is 1940, and we’re nearly half-way through the novel when this climactic moment arrives. What we have, at one level, is a family saga, and this necessitates a chronological approach to Bertrand’s experiences: indeed, the story begins in 1890, some years before his birth, when his mother and the mother of his future wife Madeleine Bonnet are a couple of convent school girls.

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.