Hattersley’s Specifics

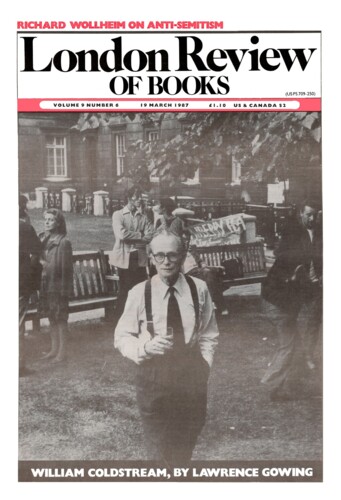

Michael Stewart, 19 March 1987

Tony Crosland’s epoch-making book The Future of Socialism was published in 1956. That Roy Hattersley’s aim is to don the master’s mantle in the late 1980s is evident not only from his book’s subtitle, but also from his brief account of a conversation he had with Tony Crosland a week before the latter’s fatal stroke. ‘Give me,’ said Crosland, ‘a simple definition of socialism’. Hattersley obligingly failing to do this, Tony Crosland did it himself. ‘Socialism,’ he said, ‘is about the pursuit of equality and the protection of freedom – in the knowledge that until we are truly equal we will not be truly free’. It is that self-evident truth, says Hattersley, that his book seeks to demonstrate. (Subtle politician that he is, Hattersley refers us to Susan Crosland’s biography of her husband ‘for a full account of the conversation’ between him and Crosland. In fact, Mrs Crosland’s book contains hardly any fuller an account: but it does contain ample evidence of the fact that Tony Crosland liked Roy Hattersley. Ah well, that’s showbiz.)’