Michael Neve

Michael Neve is a lecturer in the History of Medicine at University College, London.

The Sun-Bather

Michael Neve, 3 July 1980

After sex, sexology. The making of many extravagant theories about nature’s mysteries is not particularly new, and wasn’t even in the 19th century. Indeed, that century can be seen as a spawning ground for all kinds of ambitious intellectual projects, grand ‘totalisations’ of the varied phenomena of nature and society. Sociology, itself the product of a general feeling that mére history was too narrow a form, has perhaps been the most resilient of these creations. Sexology is certainly the most curious. As writers such as Stuart Hampshire have reiterated, almost all the grand syntheses attempted by the 19th-century intelligentsia share a common aim: to replicate, as far as possible, the achievements and accuracies of the natural sciences. This is as true of the tedious volumes of Herbert Spencer, who needed a special chair, fitted with nails, to stop him falling asleep, as it is of Marxism. It holds, too, for the spate of scientific programmes, many of them German in origin, that were laid down for the attack on the final citadel: sex. Towards the end of the 19th century, science turned its gaze on the thing itself. Unsurprisingly, the campaign produced its own particular range of prophets, seers and sages. Almost all of them were men, and men who shared some physical similarities, if nothing else. Sad eyes, perhaps; beards certainly. Freud remains by far the most powerful and influential, possibly because he was the most pessimistic. Havelock Ellis (1859-1939) seems more elusive.

Bliss

Michael Neve, 16 October 1980

Cleanliness has always been next to godliness: Christopher Isherwood (‘this rebellious son of a British lieutenant-colonel’ – Time Magazine) has found the two things in California, where they have become One. My Guru and his Disciple, an account of Isherwood’s relationship with the Swami Prabhavananda in the gentle climes of the West Coast, is clear-sighted and clean-limbed, a relaxed vision of love and devotion, a diary that records difficulties effortlessly and remembers trials as periods of intense relaxation. The wisdom of the Vedas is now found in the Pacific ocean in the early morning; God inhabits a blank and quiet world, where the sun always shines and all backgrounds have become foregrounds:

Sexual Politics

Michael Neve, 5 February 1981

The British were the only people who went through both world wars from beginning to end. Yet they remained a peaceful and civilised people, tolerant, patient and generous. Traditional values lost much of their force. Other values took their place. Imperial greatness was on the way out: the welfare state was on the way in. The British Empire declined: the condition of the people improved. Few now sang ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. Few even sang ‘England Arise’. England had risen all the same.

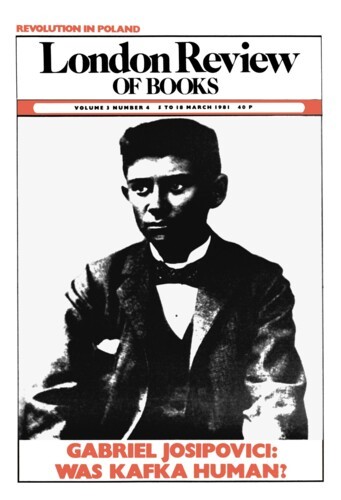

Guilty Men

Michael Neve, 5 March 1981

Philip Larkin’s lines have taken hold over the years, calling to them the confirmatory evidence of family histories, uniting disparate and apparently unconnected offspring under their aegis. Few authors in recent fiction have addressed themselves to the universal family romance with Caroline Blackwood’s bleakness. In her previous novels, The Stepdaughter and Great Granny Webster, the outlines of parental tyranny, of domination and resistance, were memorably etched. Mum and Dad could fuck you up in the simplest of ways – by simply not wanting you. These stories, which do not of course confine themselves to mums and dads, seem to have become a kind of public record: no longer ordinary fictions, however elegant, brutish and short, but something larger, with a historical reach that makes the issues of abandonment and waste something to be answered within the community, and not merely half-remembered at the novel’s close. Whose children are they, in the end, these orphans, fictional and yet also real presences? She seems to be writing a history of the family, but one that is not confined to History.

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.