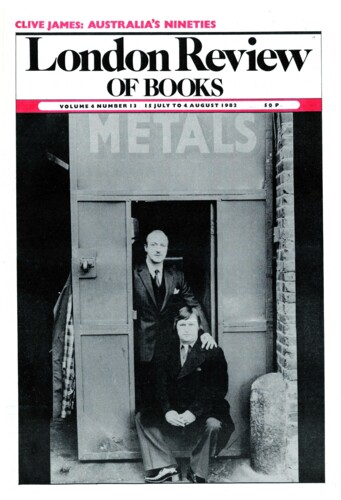

Daddy’s Boy

Michael Ignatieff, 22 December 1983

The media attention accorded to acts of infamy may or may not figure in the motivations of mass killers, but it must certainly count among the compensations of homicide as a moral career. In the wake of his conviction for murdering and dismembering six lonely young men at that dreaded address, Cranley Gardens, Muswell Hill, Dennis Nilsen must have basked in the thought that, even behind bars, he was still free to roam through the darker corners of the minds of all those people who had scorned or ignored him when he was a Job Centre counsellor and a pub bore.