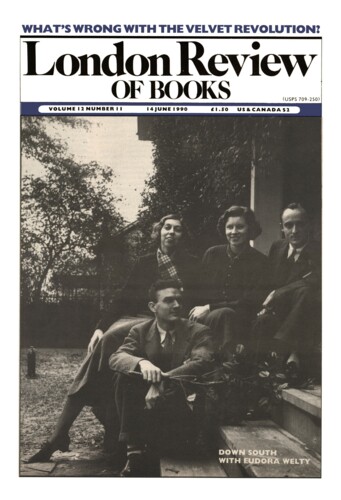

Hot Dogs

Malcolm Bull, 14 June 1990

In recent years, nothing has done more to reinforce the European sense of cultural superiority than the sight of America’s televangelists. Easily stereotyped as politically reactionary, sexually hypocritical, intellectually retarded and financially dishonest, the televangelists confirmed every prejudice about American society. That such men should be allowed, not only to appear on television, but to run for the Presidency of the United States, is taken as proof of the immaturity of the nation’s social institutions and the inherent gullibility of its people. Whatever the weaknesses of European civilisation, it has been possible to take comfort in its relative secularity; Europe, at least until the Rushdie affair, seemed immune during the worldwide resurgence of fundamentalism – the one place where religious fanatics remained at the margins of public life.’