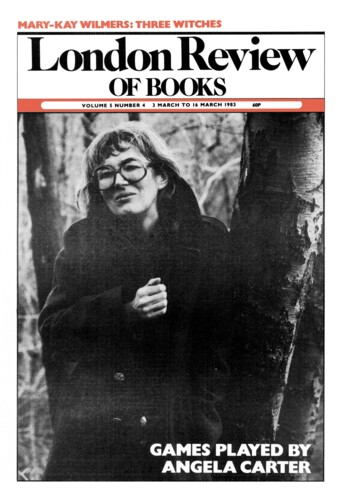

The Pouncer

Julian Barnes, 3 March 1983

I’ve been having these bad dreams about David Plante recently. Sometimes, I am slumped on the lavatory, glued there by gin and self-pity; sometimes, I am watching The Sound of Music on television and bawling shameful tears; sometimes, I am driving bad-temperedly through the Tuscan countryside, railing foolishly at the world’s treatment of me. Always Mr Plante is at my side: on his face a winning smile, and behind his back a betraying notebook.