Jonathan Rée

Jonathan Rée was a professor of philosophy at Middlesex Polytechnic until he gave up teaching, as he has put it, to have more time to think. His books include Proletarian Philosophers, Philosophical Tales, Heidegger and Witcraft: The Invention of Philosophy in English. He has also edited his father’s memoirs of fighting in the French Resistance, published by Yale as A Schoolmaster’s War. He presented ‘Conversations in Philosophy’, an LRB Close Readings podcast series, with James Wood. Ten of his pieces for the LRB, on thinkers from Spinoza to Sartre, have been collected in an audiobook, Becoming a Philosopher.

Mend and Extend: Ernst Cassirer’s Curiosity

Jonathan Rée, 18 November 2021

Ernst Cassirer got a warm welcome when he moved to the United States in 1941. He was a near perfect embodiment of the idea of the great European thinker: not only a multilingual intellectual historian, doubtless familiar with every significant document of Western civilisation, but also a synoptic philosopher who had explored the deep questions that animate cultures and give meaning to...

The Young Man One Hopes For: The Wittgensteins

Jonathan Rée, 21 November 2019

Wittgenstein’s scepticism about logical ‘objects’ was an affront to all that Bertrand Russell held dear, and he resisted it fiercely. But then he was mollified by a gift of ‘lovely roses’: Wittgenstein was ‘<em>the</em> young man one hopes for’, he now wrote to Ottoline Morrell, and ‘I like him very much.’ After undergoing further bouts of ruthless criticism, he confessed to being ‘strangely excited’ by Wittgenstein: ‘I love him,’ he said, and he hoped to appoint him as his successor and watch him ‘solve the problems I am too old to solve’. Wittgenstein wasn’t particularly impressed by Russell’s adoration. If his philosophical capacities were as exceptional as Russell seemed to think, then this was a curious fact – like having beautiful ears or excellent eyesight – but not an occasion for pride, still less for boasting.

Peas in a Matchbox: ‘Being and Nothingness’

Jonathan Rée, 18 April 2019

At the turn of the 20th century, Gaston Gallimard was one of many suave young men about Paris with exquisite taste in literature, music and art. Then he became friends not only with Proust, but also with Gide, who in 1908 started the monthly Nouvelle Revue Française in the hope of helping a ‘rising generation’ to escape the suffocating plushness of...

Blame it on Darwin

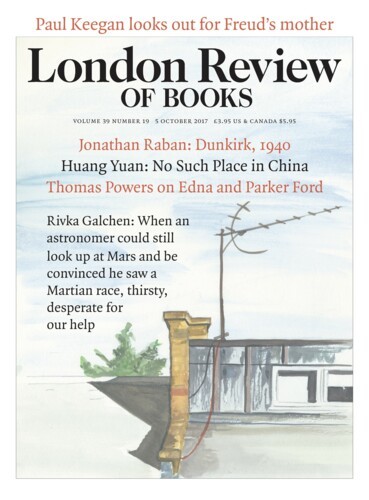

Jonathan Rée, 5 October 2017

When the 22-year-old Charles Darwin joined HMS Beagle in 1831 he took a copy of Paradise Lost with him, and over the next five years he read it many times, in Brazil, Patagonia, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and Mauritius. As the ship’s naturalist he sent commentaries and specimens back to colleagues in London, who soon came to see him not as a dilettante but an extremely acute...

Podcasts & Videos

The Hayek Puzzle

Jonathan Rée and Thomas Jones

Following his review of a new biography, Jonathan Rée speaks to Tom about Friedrich Hayek’s celebrity and infamy, and the ways close reading reveals surprising nuance in his work.

What do you mean by ‘God’?

Jonathan Rée

Philosopher Jonathan Rée unravels the story within Spinoza's knotty work of 17th century rationalism, the Ethics

The Horror of Doubt

Jonathan Rée

Jonathan Rée considers Kierkegaard’s unfinished work, Johannes Climacus, about a student who falls in love with thinking.

Albert Camus: A Short Life

Jonathan Rée and James Wood

Albert Camus’s short life began in Algiers in 1913 and ended in a car crash near Paris in 1960. After being rejected from the École Normale because of a failed medical assessment, Camus became a journalist...

Pieces about Jonathan Rée in the LRB

The Bad News about the Resistance: Parachuted into France

Neal Ascherson, 30 July 2020

Harry Rée wanted his British audience to understand that the French men and women who had taken part in the Resistance were not superhuman. ‘What I shall try to get across,’ he told a symposium in...

Gabble, Twitter and Hoot: language, deafness and the senses

Ian Hacking, 1 July 1999

Jonathan Rée takes some tomfoolery from Shakespeare for his title and uses it to create his own striking metaphor. The middle part of his book is about sign languages for the deaf: voices...

Thou shalt wage class war

Gareth Stedman Jones, 1 November 1984

Sometime in the late Sixties, I was invited, along with some senior socialist historians, to meet Bill Craik, a veteran and pioneer, so I was told, of independent working-class education. The...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.