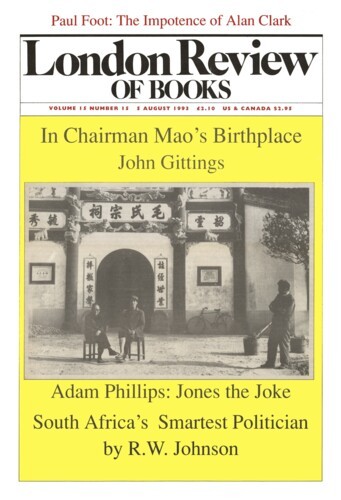

I arrived by bus at a dusty crossroads outside Shaoshan, the birthplace of Mao Zedong, in a fine mist which stippled the dark water of the paddy fields. An out-of-work student with a motorbike for hire drove me to the Shaoshan Guesthouse. It was damp and empty except for a group of civil servants visiting at official expense. In the village square, some workers were desultorily clearing the ground where a statue of Mao is to be erected – the first in nearly twenty years. On 26 December, China will commemorate the l00th anniversary of his birth. At the Guesthouse the choice was between a tourist room with three single beds and dirty sheets, or Mao Zedong’s old suite, which had a double bed with a wooden canopy and a bath almost as large, at five times the price. I chose the suite, less for the clean sheets than for the opportunity to sit at his desk, listen to the wind in the bamboos outside, study the ink spots on the worn leather, and think about the Chairman.’

I arrived by bus at a dusty crossroads outside Shaoshan, the birthplace of Mao Zedong, in a fine mist which stippled the dark water of the paddy fields. An out-of-work student with a motorbike...