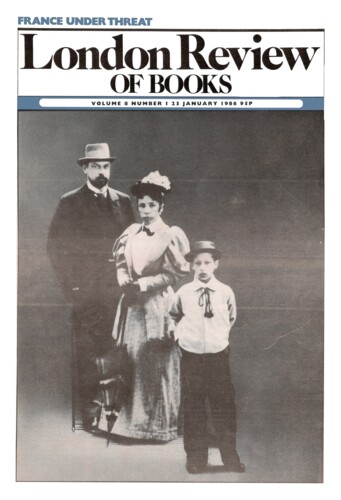

Bertie pulls it off

John Campbell, 11 January 1990

The British monarchy was tested almost to destruction in 1936-37. The crisis had three phases, of which the actual abdication of King Edward VIII was only the most visible. The monarchy had already been placed under acute strain by Edward’s unkingly conduct in the few months since his father’s death – his feckless hedonism, his dangerous political naivety and his neglect of the more tedious duties of his role. His abdication – an entirely characteristic act of childish stubbornness – was an unprecedented shock to a system founded upon precedent: yet to most of those who had seen his inadequacy at close quarters it was a relief – or would have been if there had not been serious doubt whether his brother the Duke of York was up to the job either. His health was poor, he suffered from a severe stammer and he lacked even Edward’s vapid charm. For some months – while the American press speculated that the new king was ‘of poorer royal timber than has occupied England’s throne in many decades’ – courtiers and royal-watchers held their breath to see if ‘Bertie’ would make out. In fact, the responsibility thrust upon him brought out unsuspected qualities in George VI, and the institution emerged from the trial stronger in public affection than ever before.’