Jane Miller

Jane Miller’s books include Crazy Age and In My Own Time. She first wrote for the LRB in 1979.

Gissing may damage your health

Jane Miller, 7 March 1991

My great-aunt Clara and George Gissing were friends during the last ten years of his life. He wrote to her about once a week, always as Miss Collet, and quite often bared his soul to her. She was an expert on women’s work and a civil servant. During his lifetime she gave him money to educate his sons, and after he died she not only arranged with Downing Street for a Civil List pension for them. ‘in recognition of the literary services of their father and of his straitened circumstances’, but also managed to get several of his novels reissued. That is why I grew up amongst two-inch-thick, plum-coloured volumes of The Whirlpool and the rest, in what might well be thought of as a two-Veranilda household. I must admit, however, that though Eve’s Ransom and The Crown of Life did well as bed legs and door-stops, they were not much read. And though Clara herself was probably at least half in love with George Gissing, it isn’t clear that she liked his novels very much either. Indeed, as she wrote some years later, she disliked The Odd Women ‘so much that I nearly did not make George Gissing’s acquaintance because of it’: which is not so surprising, perhaps, since more than one Gissing scholar has claimed that his novel drew on his relations with Clara, even though it was written before they met.

My Friend Sam

Jane Miller, 16 August 1990

The landscape of Ellen Douglas’s Mississippi is designed to keep us out, to resist recognition; and the lines of its knobs and bluffs and ridges may be deciphered only by those who have been born and bred amongst them. For the rest of us they are edged but also obscured by lovingly named plants, by smilax, trillium, scuppernog vines and plum thickets. And the birds in their midst, the towhees, the goatsuckers, the magnolia warblers and juncos, do not sing to us out of some shared childhood, but out of memories we are adjured to hear as entirely different from our own. They will be mythic and mysterious memories, but they will also – so consciously Southern is this (and so much other) writing from the American South – be delivered with due attention paid to the clichés to be navigated therein. Leafless briars viciously obstruct the solitary wanderer in this landscape, and so does the barbed wire surrounding the government defence station, whose recent installation has added itself to a history of depredations of the land. It is as if it is only possible to enter these places and their past with a local guide and through literature.’

Blaming teachers

Jane Miller, 17 August 1989

On the first day of the school holidays – and the hottest day for 13 years – 650 London teachers of English from secondary and primary schools met to discuss the implications of the second volume of the Cox Report. The volume elaborates a set of proposals for the teaching of language and literature to all children between five and 16 who attend state schools and who will be embarking on the first stages of the new National Curriculum from this September. The day was organised by teachers and paid for by them. It was necessary to raise an extra £1600 in order to give everybody a photocopy of the report. Publications of this kind thud onto desks and doorsteps continuously, and they are free. However, the DES does not send copies to ordinary classroom teachers and was not prepared to let the day’s organisers have more than 50 copies.’

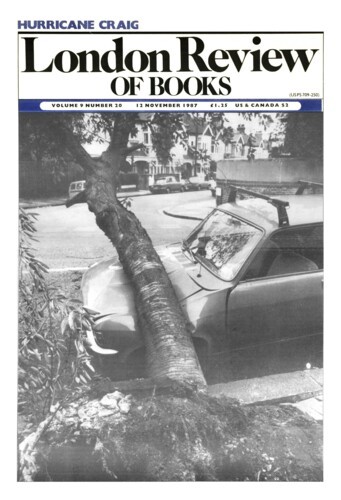

Understanding slavery

Jane Miller, 12 November 1987

Toni Morrison’s novels have been constructed, and are magically unsettled, by the unique character of historical memory for black Americans. That is to say, she has wanted to account for black experience that has been ignored or quite inadequately narrated by white historians and novelists, and even more significantly, in order to do that she has needed to confront precisely those aspects of the experience which have blocked memory, made remembering intolerable and memories inexpressible, literally unspeakable. Indeed, the verb ‘rememory’ is invented in her astonishing novel, Beloved, to stand for something like a willed remembering which includes its own strenuous reluctance to return to the past.

Pieces about Jane Miller in the LRB

What We Are Last: Old Age

Rosemary Hill, 21 October 2010

There is something irreducible about old age, even now when, in the West at least, the several stages of life have become blurred. The Ages of Man, which until the 1950s seemed as distinct as the...

Feminist Perplexities

Dinah Birch, 11 October 1990

Not so long ago, the most prestigious intellectual work, in the arts as in the sciences, was supposed to be impersonal. The convention was that the circumstances in which such work was produced...

Pen Men

Elaine Showalter, 20 March 1986

One of the more useful side-effects of the widely-publicised troubles at the International PEN Congress held this January in New York may ironically have been the new timeliness which Norman...

Gift of Tongues

John Edwards, 7 July 1983

Bilingualism, multiculturalism, ethno-linguistic identity – they may not be words to conjure with, but much conjuring has nevertheless been done with them. Even the most casual observer can...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.